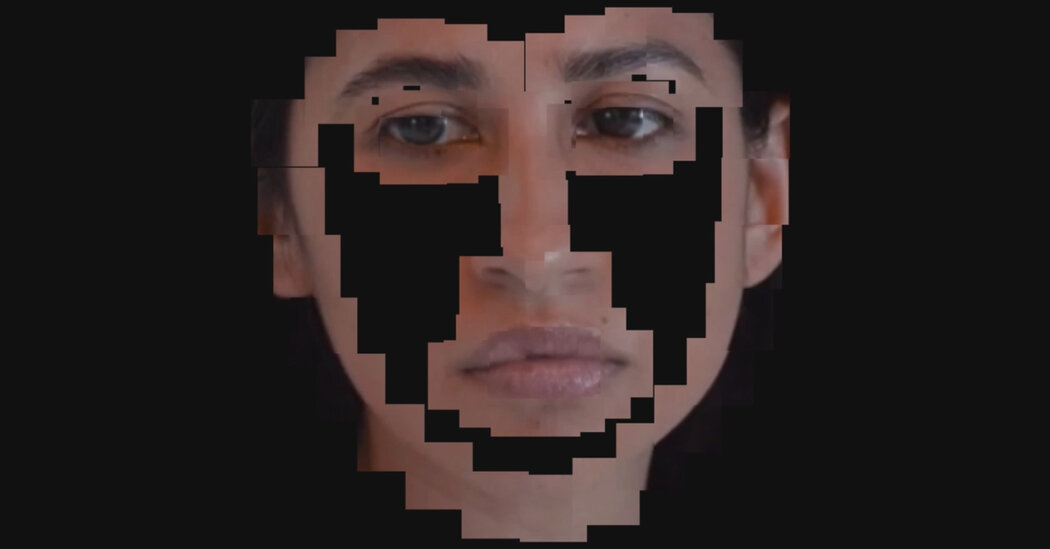

When a secretive start-up scraped the internet to build a facial-recognition tool, it tested a legal and ethical limit — and blew the future of privacy in America wide open.

The New York Times has an in depth story about Clearview AI titled, Facial Recognition: What Happens When We’re Tracked Everywhere We Go? The story tracks the various lawsuits attempting to stop Clearview and suggests that Clearview may well win. They are gambling that scraping the web’s faces for their application, even if it violated terms of service, may be protected as free speech.

The story talks about the dangers of face recognition and how many of the algorithms can’t recognize people of colour as accurately which leads to more false positives where police end up arresting the wrong person. A broader worry is that this could unleash tracking at another scale.

There’s also a broader reason that critics fear a court decision favoring Clearview: It could let companies track us as pervasively in the real world as they already do online.

The arguments in favour of Clearview include the challenge that they are essentially doing to images what Google does to text searches. Another argument is that stopping face recognition enterprises would stifle innovation.

The story then moves on to talk about the founding of Clearview and the political connections of the founders (Thiel invested in Clearview too). Finally it talks about how widely available face recognition could affect our lives. The story quotes Alvaro Bedoya who started a privacy centre,

“When we interact with people on the street, there’s a certain level of respect accorded to strangers,” Bedoya told me. “That’s partly because we don’t know if people are powerful or influential or we could get in trouble for treating them poorly. I don’t know what happens in a world where you see someone in the street and immediately know where they work, where they went to school, if they have a criminal record, what their credit score is. I don’t know how society changes, but I don’t think it changes for the better.”

It is interesting to think about how face recognition and other technologies may change how we deal with strangers. Too much knowledge could be alienating.

The story closes by describing how Clearview AI helped identify some of the Capitol rioters. Of course it wasn’t just Clearview, but also a citizen investigators who named and shamed people based on photos released.