The London Review of Books has a blog entry by Eyal Weizman on how The algorithm is watching you (Feb. 19, 2020). Eyal Weizman, the founding director of Forensic Architecture, writes that he was denied entry into the USA because an algorithm had identified a security issue. He was going to the US for a show in Miami titled True to Scale.

Setting aside the issue of how the US government seems to now be denying entry to people who do inconvenient investigations, something a country that prides itself on human rights shouldn’t do, the use of an algorithm as a reason is disturbing for a number of reasons:

- As Weizman tells the story, the embassy officer couldn’t tell what triggered the algorithm. That would seem to violate important principles in the use of AIs; namely that an AI used in making decisions should be transparent and able to explain why it made the decision. Perhaps the agency involved doesn’t want to reveal the nasty logic behind their algorithms.

- Further, there is no recourse, another violation of principle for AIs, namely that they should be accountable and there should be mechanisms to challenge a decision.

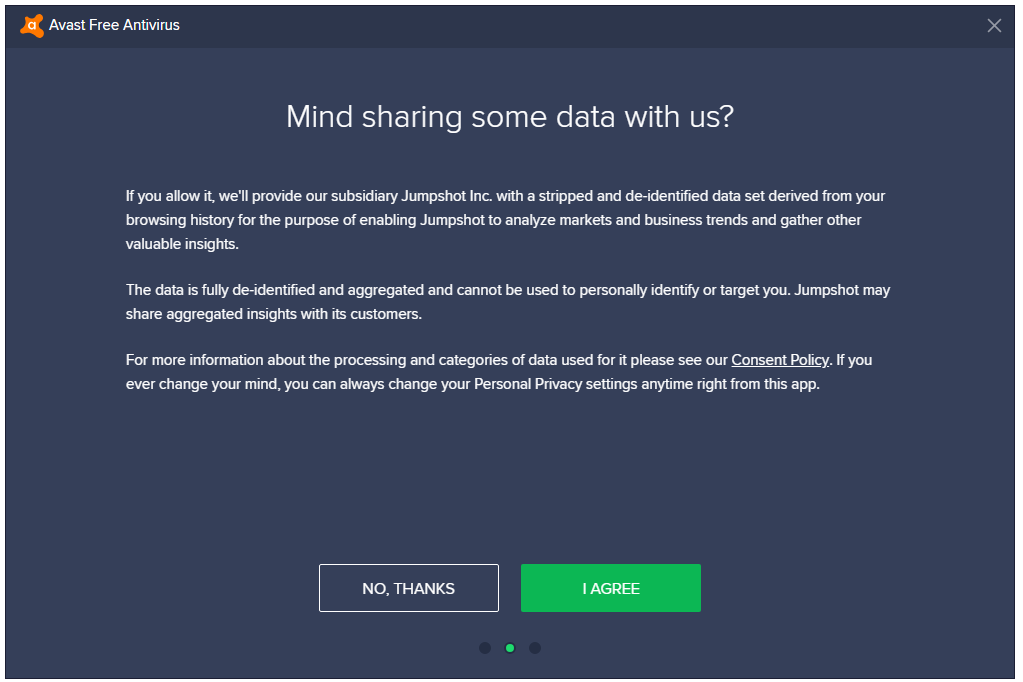

- The officer then asked Weizman to provide them with more information, like his travel for the last 15 years and contacts, which he understandably declined to do. In effect the system was asking him to surveil himself and share that with a foreign government. Are we going to be put in the situation where we have to surrender privacy in order to get access to government services? We do that already for commercial services.

- As Weizman points out, this shows the “arbitrary logic of the border” that is imposed on migrants. Borders have become grey zones where the laws inside a country don’t apply and the worst of a nation’s phobias are manifest.