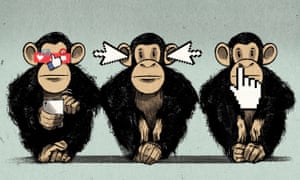

Is “excellence” really the most efficient metric for distributing the resources available to the world’s scientists, teachers, and scholars? Does “excellence” live up to the expectations that academic communities place upon it? Is “excellence” excellent? And are we being excellent to each other in using it?

During the panel today on Journals in the digital age: penser de nouveaux modèles de publication en sciences humaines at CSDH-SCHN 2020 someone linked to an essay on “Excellence R Us”: university research and the fetishisation of excellence in Palgrave Communications (2017). The essay does what should have been done some time ago, it questions the excellence of “excellence” as a value for everything in universities. The very overuse of “excellence” has devalued the concept. Surely much of what we do these days is “good enough” especially as our budgets are cut and cut.

The article has three major parts:

- Rhetoric of excellence – it looks at how there is little consensus around what excellence between disciplines. Within disciplines it is negotiated and can become conservative.

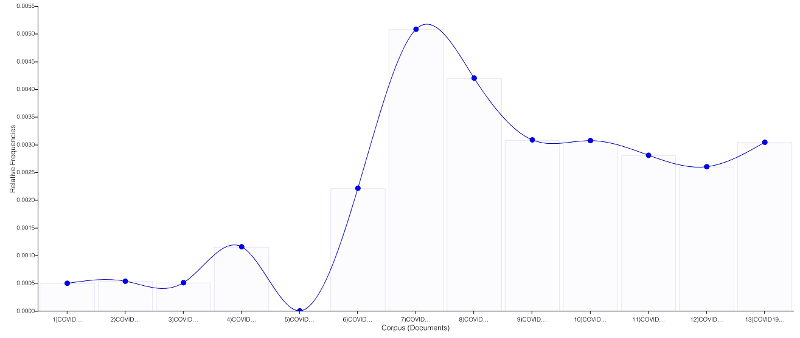

- Is “excellence” good for research – the second section argues that there is little correlation between forms of excellence review and long term metrics. They go on to outline some of the unfortunate side-effects of the push for excellence; how it can distort research and funding by promoting competition rather than collaboration. They also talk about how excellence disincentivizes replication – who wants to bother with replication if

- Alternative narratives – the third section looks at alternative ways of distributing funding. They discuss looking at “soundness” and “capacity” as an alternatives to the winner-takes-all of excellence.

So much more could and should be addressed on this subject. I have often wondered about the effect of the success rates in grant programmes (percentage of applicants funded). When the success rate gets really low, as it is with many NEH programmes, it almost becomes a waste of time to apply and superstitions about success abound. SSHRC has healthier success rates that generally ensure that most researchers gets funded if they persist and rework their proposals.

Hypercompetition in turn leads to greater (we might even say more shameless …) attempts to perform this “excellence”, driving a circular conservatism and reification of existing power structures while harming rather than improving the qualities of the underlying activity.

Ultimately the “adjunctification” of the university, where few faculty get tenure, also leads to hypercompetition and an impoverished research environment. Getting tenure could end up being the most prestigious (and fundamental) of grants – the grant of a research career.