Catalogue of billions of phrases from 107 million papers could ease computerized searching of the literature.

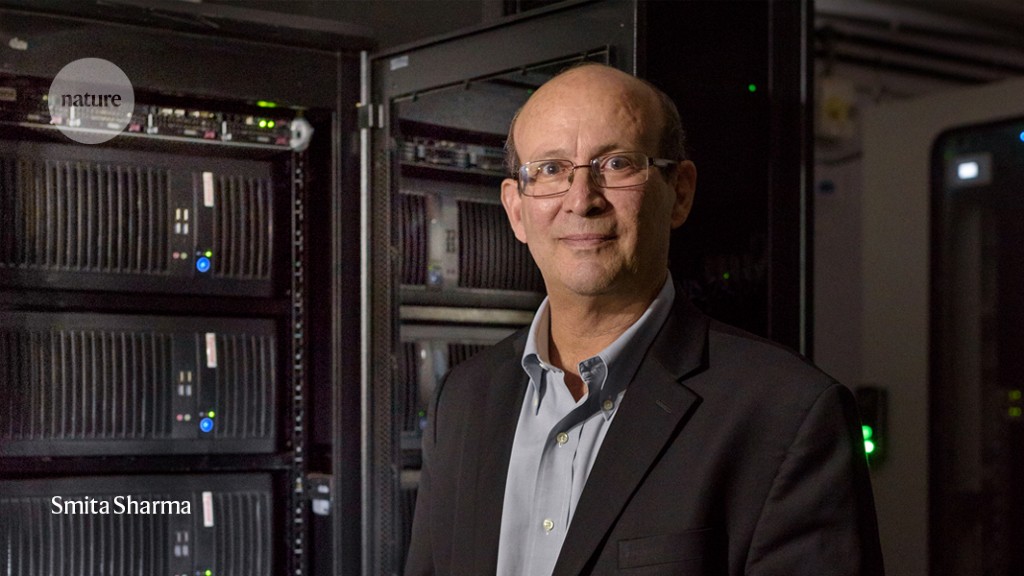

From Ian I learned about a Giant, free index to world’s research papers released online. The General Index, as it is called, makes ngrams of up to 5 words available with pointers to relevant journal articles.

The massive index is available from the Internet Archive here. Here is how it is described.

Public Resource, a registered nonprofit organization based in California, has created a General Index to scientific journals. The General Index consists of a listing of n-grams, from unigrams to five-grams, extracted from 107 million journal articles.

The General Index is non-consumptive, in that the underlying articles are not released, and it is transformative in that the release consists of the extraction of facts that are derived from that underlying corpus. The General Index is available for free download with no restrictions on use. This is an initial release, and the hope is to improve the quality of text extraction, broaden the scope of the underlying corpus, provide more sophisticated metrics associated with terms, and other enhancements.

Access to the full corpus of scholarly journals is an essential facility to the practice of science in our modern world. The General Index is an invaluable utility for researchers who wish to search for articles about plants, chemicals, genes, proteins, materials, geographical locations, and other entities of interest. The General Index allows scholars and students all over the world to perform specialized and customized searches within the scope of their disciplines and research over the full corpus.

Access to knowledge is a human right and the increase and diffusion of knowledge depends on our ability to stand on the shoulders of giants. We applaud the release of the General Index and look forward to the progress of this worthy endeavor.

There must be some neat uses of this. I wonder if someone like Google might make a diachronic viewer similar to their Google Books Ngram Viewer available?