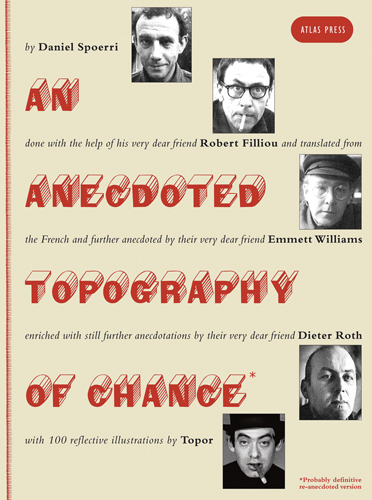

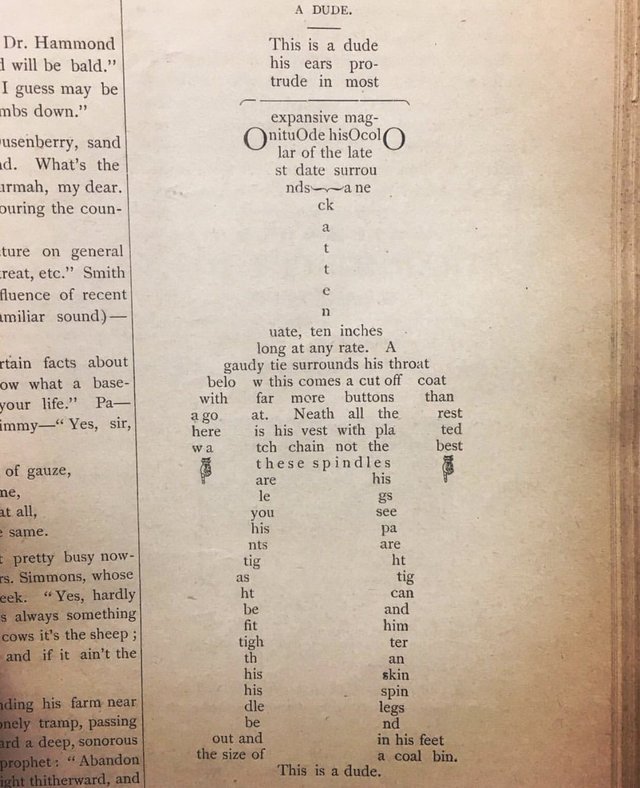

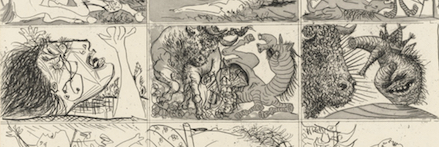

Drawing on a selection of non-keyboard ‘index’ typewriters, this exhibition explores how input mechanisms and alphabetic arrangements were devised and contested continually in the process of popularising typewrites as personal objects. The display particularly looks at how the letters of the alphabe

Reading Thomas S. Mullaney’s The Chinese Typewriter I’m struck by the variety of different typewriting solutions. As you can see from this exhibit web site, One letter at a time: index typewriters and the alphabetic interface — Contextual Alternate, there were all sorts of alternatives to the QWERTY keyboard early on, and many of them could accommodate more keys so as to support other languages including a non-alphabetic script like Chinese. As Mullaney points out there is a history to the emergence of the typewriter that we assume is normal.

This history of our collapsing technolinguistic imaginary took place across four phases: an initial period of plurality and fluidity in the West in the late 1800s, in which there existed a diverse assortment of machines through which engineers, inventors, and everyday individuals could imagine the very technology of typewriting, as well as its potential expansion to non-English and non-Latin writing systems; second, a period of collapsing possibility around the turn of the century in which a specific typewriter form—the shift-keyboard typewriter—achieved unparalleled dominance, erasing prior alternatives first from the market and then from the imagination; next, a period of rapid globalization from the 1900s onward in which the technolinguistic monoculture of shift-keyboard typewriting achieved global proportions, becoming the technological benchmark against which was measured the “efficiency” and thus modernity of an ever-increasing number of world scripts; and, finally, the machine’s encounter with the one world script that remained frustratingly outside its otherwise universal embrace: Chinese.

Mullaney, Thomas S.. The Chinese Typewriter (Kindle Locations 1183-1191). MIT Press. Kindle Edition.