Elon Musk thinks a free market of ideas will self-correct. Liberals want to regulate it. Both are missing a deeper predicament.

Jennifer Szalai of the New York Times has a good book review or essay on misinformation and disinformation, Elon Musk, X and the Problem of Misinformation in an Era Without Trust. She writes about how Big Tech (Facebook and Google) benefit from the view that people are being manipulated by social media. It helps sell their services even though there is less evidence of clear and easy manipulation. It is possible that there is an academic business of Big Disinfo that is invested in a story about fake news and its solutions. The problem instead may be a problem of the authority of elites who regularly lie to the US public. This of the lies told after 9/11 to justify the “war on terror”; why should we believe any “elite”?

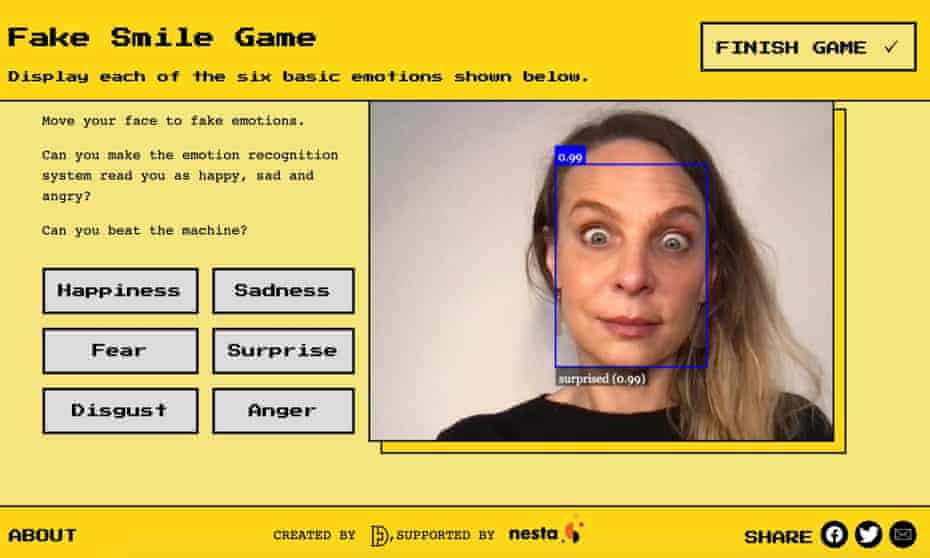

One answer is to call people to “Do your own research.” Of course that call has its own agenda. It tends to be a call for unsophisticated research through the internet. Of course, everyone should do their own research, but we can’t in most cases. What would it take to really understand vaccines through your own research, as opposed to joining some epistemic community and calling research the parroting of their truisms. With the internet there is an abundance of communities of research to join that will make you feel well-researched. Who needs a PhD? Who needs to actually do original research? Conspiracies like academic communities provide safe haven for networks of ideas.