Imagine, if you can, a small room, hexagonal in shape, like the cell of a bee. It is lighted neither by window nor by lamp, yet it is filled with a soft radiance. There are no apertures for ventilation, yet the air is fresh. There are no musical instruments, and yet, at the moment that my meditation opens, this room is throbbing with melodious sounds. An armchair is in the centre, by its side a reading-desk — that is all the furniture. And in the armchair there sits a swaddled lump of flesh — a woman, about five feet high, with a face as white as a fungus. It is to her that the little room belongs.

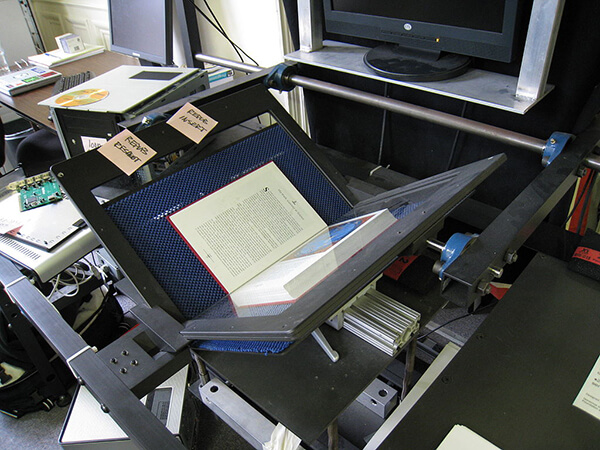

Like many, I reread E.M. Forester’s The Machine Stops this week while in isolation. This short story was published in 1909 and written as a reaction to The Time Machine by H.G. Wells. (See the full text here (PDF).) In Forester it is the machine that keeps working the utopia of isolated pods; in Wells it is a caste of workers, the Morlochs, who also turn out to eat the leisure class. Forester felt that technology was likely to be the problem, or part of the problem, not class.

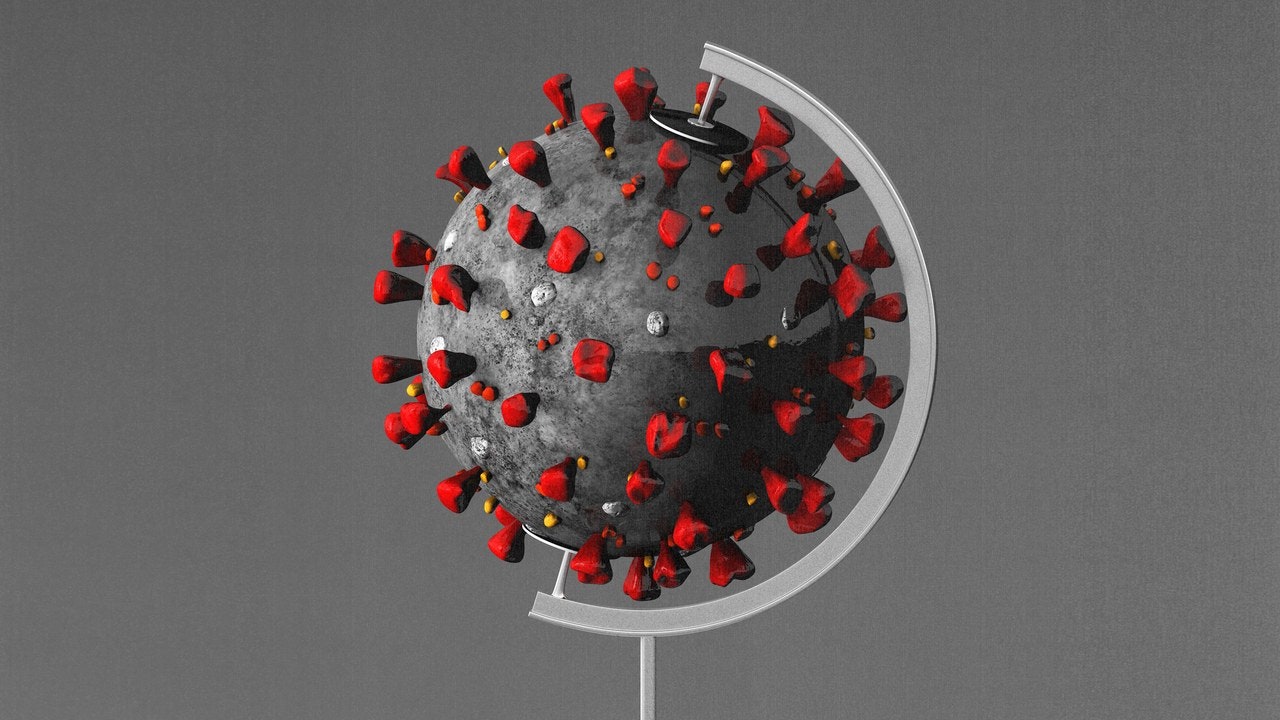

In this pandemic we see a bit of both. Following Wells we see a class of gig-economy deliverers who facilitate the isolated life of those of us who do intellectual work. Intellectual work has gone virtual, but we still need a physical layer maintained. (Even the language of a stack of layers comes metaphorically from computing.) But we also see in our virtualized work a dependence on an information machine that lets our bodies sit on the couch in isolation while we listen to throbbing melodies. My body certainly feels like it is settling into a swaddled lump of fungus.

An intriguing aspect of “The Machine Stops” is how Vashti, the mother who loves the life of the machine, measures everything in terms of ideas. She complains that flying to see her son and seeing the earth below gives her no ideas. Ideas don’t come from original experiences but from layers of interpretation. Ideas are the currency of an intellectual life of leisure which loses touch with the “real world.”

At the end, as the machine stops and Kuno, Vashti’s son, comes to his mother in the disaster, they reflect on how a few homeless refugees living on the surface might survive and learn not to trust the machine.

“I have seen them, spoken to them, loved them. They are hiding in the mist and the ferns until our civilization stops. To-day they are the Homeless — to-morrow—”

“Oh, to-morrow — some fool will start the Machine again, to-morrow.”

“Never,” said Kuno, “never. Humanity has learnt its lesson.”