Michael Bérubé has written an important essay in The Chronicle titled The Humanities, Unraveled. He revisits the question of accepting all these grad students for whom there aren’t jobs and, following an essay No More Plan B by Anthony Grafton, makes the case for graduate programmes designed for alternative careers.

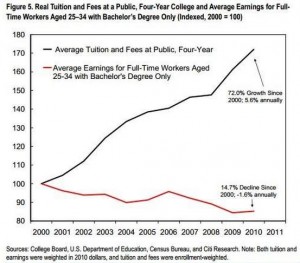

[W]hen we look at the public reputation of the humanities; when we compare the dilapidated Humanities Cottage on campus with the new $225-million Millennium Science Complex thats a real example, from my home institution; when we look at the academic job market for humanists, we cant avoid the conclusion that the value of the work we do, and the way we theorize value, simply isnt valued by very many people, on campus or off.

The alt-ac community poses a timely and bracing challenge to that attitude. It asks us what graduate curricula might be most readily transferable to careers outside academe perhaps curricula that include semester-long internships and/or administrative experience?—and whether those careers will be honored and validated by deans and provosts, who remain likely to evaluate the success of graduate programs in the humanities by their placement rates, which are likely to continue to refer exclusively to placements in academic positions.

I think the time has come to stop talking about Alt-Ac careers as only an alternative and start seriously designing graduate programmes for Alt-Ac first. Why first? Because I think the academy would actually benefit from students prepared for Alt-Ac. So what should we be thinking about?

- Despite what Grafton says, we should scale back the dissertation to something that can be written in a year or two. We have to scale it back or be open to alternative dissertations so that there is time/opportunity for other things. We should encourage project driven dissertations and funded dissertations where a Ph.D student is funded by a research team to do their research on the subject of the grant as part of the team. This is normal in the sciences and engineering and leads to faster completion times and healthier interaction between student and team. Imagine working on a thesis other people were actually interested in because it connected to what they were doing? Imagine being funded to complete in a timely fashion?

- We should stop trying to protect graduate students from things like internships, other disciplines, computing, and yes … jobs. Instead we should encourage them to try the things they are interested in while they have time. While for many of us the time of writing the dissertation has become an idealized moment of peace and focus before the chaos of a job, that doesn’t mean that is the only way to be a graduate student. Lets encourage students to get breadth along with some depth.

- Whether we leave the dissertation as is, we should change how they are supervised to make sure that students get more open and broad support. There are all sorts of healthy models out there that are less feudal. Even if we leave things as is we should expect of ourselves that read the literature (and university policies) about best practices in supervision. To my colleagues who supervise – RTFM!

- The trend has been to get rid of Masters programmes and focus on the PhDs. Direct-entry PhDs generate more money, but they are creating a situation where students have no way to test the waters before entering immediately into a stick-it-out-for-years-or-fail programme. I think this is a mistake as a significant MA could be the Alt-Ac degree, freeing the PhD to be the academic extension. Our 2 year MA in Humanities Computing has a thesis that forces students to embark on a substantial project. The two years give them enough time to learn skills and then apply them. Most take a third year either because they are in the joint MA/MLIS programme that gives them the professional degree or because they involved in so many neat projects (for which they are paid.) Most of our students have no trouble getting work even before they finish and it is because the programme gives them real apprenticing opportunities.

- We should break down the disciplinary barriers that make it difficult for students to take courses in other department or for students to apply to do an interdisciplinary PhD. Despite the best of intentions, students who want to cross boundaries find they have to do all the requirements for both units. There are all sorts of reasons for this and interdisciplinary escape hatches are expensive to maintain for the number of students that take them, but it should still possible and we should be vigilant to maintain those escape hatches. It would be interesting to imagine more radical approaches (as in accepting students into the humanities and helping them to develop their own programme.)

- We should get away from the sacred 3 unit – one semester course. We should encourage shorter intense courses and longer languid ones. I learned Aristotle by taking two solid, but slow years of it with a prof who basically had us think about a page of Aristotle a week. We went so slow it began to make sense as a way of thinking. Likewise I’ve been at intense retreats like THATcamps where I learn a lot in four days. Such short courses can help students engage a breadth of Alt-Ac perspectives without making too much of a commitment.

- Comprehensives and other forms of exams should be thrown out and replaced with internships, experiential applications, project apprenticeships or teaching apprenticeships. Lets give PhD students a choice of professional experiences instead of exams. Ask students to embark on 3 projects (from a teaching project to a community-based one) and then report back in different ways. That would give us a much better measure of whether a student was ready to write about a subject so as to make a career of it. Exams just relieve our fears of granting degrees to people who don’t know enough when the problem is we are granting degrees to people who can’t do much.

- Make it easy to do a graduate degree part-time. Many of the people who would actually benefit from an MA or PhD already have careers. Why aren’t we helping them expand their horizons and acquire knowledge/skills within the context of a real career? Many of our students end up working almost full time anyway, why not recognize the realities of their lives. We no longer live in a world that can provide a 7 year retreat experience for any more than a handful of students. Part-time students should be our primary audience, not an add on.

- Build graduate programs across universities. It is doubtful that universities will have the new resources to be able to start new graduate programs unless we collaborate. We have to find ways to build multi-university programs, as difficult as they are to administer. Properly done they provide students with access to a greater breadth of faculty and experiences. They also give us the capacity to innovate without having to make the case for 5 tenure-track positions in order to start a programme.

All of these may sound too radical, and none of this is original or easy. I certainly wouldn’t want all programmes to change just for the sake of a crisis (that has lasted a while so it may not count as a crisis). Rather, I would like to see a breath of experiments from the alternative to the purist that show that humanists value what they do enough to keep on adapting it for the next generation. Lets relax the reins and give some space to those who want to experiment (or not). It may be that the best approach is one of paying attention to the care of a programme however alternative or not it is.

I should add that I think the term “alternative” is misleading. There should be nothing alternative about careers beyond the academy. Extramural careers should be the norm not the alternative.