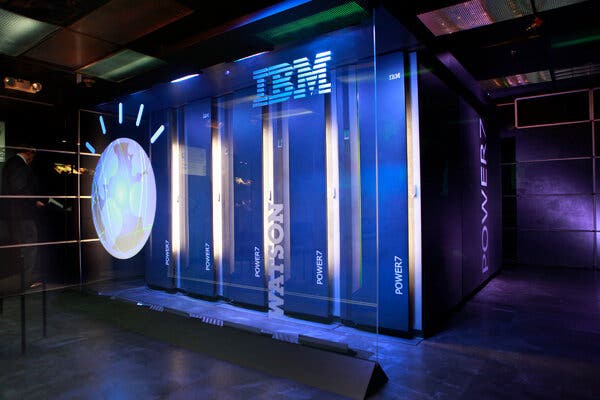

The US military is testing AI that helps predict events days in advance, helping it make proactive decisions..

Endgadget has a story on how the Pentagon believes its precognitive AI can predict events ‘days in advance’. It is clear that for most the value in AI and surveillance is prediction and yet there are some fundamental contradictions. As Hume pointed out centuries ago, all prediction is based on extrapolation from past behaviour. We simply don’t know the future; the best we can do is select features of past behaviour that seemed to do a good job predicting (retrospectively) and hope they will work in the future. Alas, we get seduced by the effectiveness of retrospective work. As Smith and Cordes put it in The Phantom Pattern Problem:

How, in this modern era of big data and powerful computers, can experts be so foolish? Ironically, big data and powerful computers are part of the problem. We have all been bred to be fooled—to be attracted to shiny patterns and glittery correlations. (p. 11)

What if machine learning and big data were really best suited for suited for studying the past and not predicting the future? Would there be the hype? the investment?

When the next AI winter comes we in the humanities could pick up the pieces and use these techniques to try to explain the past, but I’m getting ahead of myself and predicting another winter.