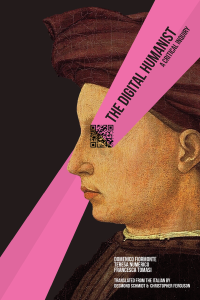

On Thursday I was part of a conference here in Verona (see my conference notes) that celebrated the seminar I led at the University of Verona and the English publication of The Digital Humanist by Domenico Fiormonte, Francesca Tomasi, and Teresa Numerico (with a Preface by me). This is the English adaptation/translation of their 2010 Italian book which has finally come out in English. Here is the edited text of my presentation. (Thanks to Domenico for helping me with the Italian!)

Dear Friends and Colleagues,

Today we are here to celebrate the end of a laboratory on digital humanities and a beginning with the publication of the The Digital Humanist: A Critical Inquiry by Domenico Fiormonte, Teresa Numerico and Francesca Tomasi.

Oggi si celebra la fine questa laboratorio che abbiamo creato insieme e una la publicazione in Inglese del libro L’umanista digitale che è stato pubblicato per la prima volta in Italiano nel 2010 e poi aggiornato e tradotto in inglese da Desmond Schmidt e Christopher Ferguson.

The English publication of this book is important to the book because part of what makes it “A Critical Inquiry” is that it questions the universality of English. I use the word universality in two senses, both of which are to be questioned:

First, that there is an assumption that we need a universal language or metalanguage – a dream of philosophers, a dream that can be said to have led to the idea of a universal machine or computer,

E secondo, uso la parola universale per il modo in cui l’Inglese invade l’informatica, dai motori di recerca ai linguaggi di programmazione, come abbiamo sentito oggi nelle presentazioni degli studenti.

Il filosofo della scienza e della tecnologia, Langdon Winner, ha scritto un bel testo dal titolo: “Do Artifacts Have Politics?” In questo articolo Winner cerca di navigare tra due posizioni opposte – quella del determinismo tecnologico che sostiene che ogni messaggio è determinato dal tecnologia–

And, he argues that neither can technologies be said to be neutral – the argument of so many technologists that relieves them of the need to take responsibility for what they develop.

Instead Winner argues that we have to attend to the artefacts themselves – some bring baggage or structure experience and some less so.

One of the great contributions of this book is just such a critical attending to the digital artefacts themselves – especially those like search engines or electronic texts that are important to us in the humanities.

Questo libro, invece di parlare dell’informatica in generale – parla delle tecnologie che usiamo come umanisti e ci aiuta a capire l’importanza del nostro lavoro – infatti direi che ci aiuta capire come dobbiamo assumerci la responsabilità per le nostre technologie.

As Heidegger and others point out, sometimes the hardest thing to do is to notice technologies that we use every day like the glasses on the end of our nose. We need to find ways back to noticing the systems of ready-to-hand in which we navigate our desires and dreams. That includes for Heidegger also noticing the way language itself structures our thinking.

But how can we do that? How can we attend? What practices can we draw on from the humanities?

Lev Manovich in an online essay talks about the comedy of breakdowns as an interruption that forces us to notice technology – something that was normal in Russia, but isn’t normal in the West.

Siegfried Zielinski – in Deep Time of the Media proposes an archaeology that pays attention to the failed technologies – the branches that have been left out of the origin myths.

This book provides, I think, three other, uniquely humanities ways into thinking again about technology:

First, it is written from the margins – at least the linguistic margins of an Anglophone discourse of technology (and digital humanities.) It was first written in Italian and draws on an Italian humanities computing tradition. The book reminds us to pay attention to language, so important to the humanities and technology too.

Second, it historicizes the technologies we take for granted – looking, for example, at key figures who imagined our cybernetic future.

Terzo, questo libro non soltanto guarda agli artefatti e ai sistemi in un modo critico, ma guarda anche ai modi in cui noi organizziamo il discorso accademico sull’informatica umanistica – direi che tratta le digital humanities come artefatto umano che deve anche essere criticato, specialmente perché siamo ciechi ai modi nei quali l’organizzazione della disciplina segue la cultura anglo-sassone. The digital humanist ci chiede di criticare come siamo e potremmo essere dei digital humanists. Questa è un questione di ethos – come viviamo con la tecnologia, come ci organizziamo per porre attenzione alla tecnologia

E’ per questo che raccomando questo libro specialmente a voi dotorandi.

For those of you just discovering the digital as a subject for humanities attention I recommend this book – it is a way in for humanists.

Voglio concludere con un commento sulla presentazione dei libri – se un libro e come una neonato – un natio come ne parlava Vico –è anche importante come il libro viene educato insegnato e interpretato.

Remember the lesson of Frankenstein. The tragedy is not that he was made of parts, but that he was abandoned at birth. The same can be said of the digital humanities – a field made of parts.

Questa e la seconda volta che aiuto a presentare questo libro. La prima volta è stata la settimana scorsa a Roma. Direi che addesso sono diventato un presentatore con esperienza nell’ allevamento. Posso annuciare il tour?

As I was just saying in Italian, this is the second time I present this book – and I’ve chosen to do it in two tongues – English and Italian. In this I’m drawing on a Canadian political tradition of bilingual presentations which I have always admired. Such bilingual talks weave two languages to make something that is not a universal language but is free of the particular blindness of a particular language.

My reason for switching is that if we are to avoid the universalizing tendency of technologies of thinking like language we have to habituate ourselves to travel back and forth translating and thinking across. That used to be obvious to the humanities, but we seem to have forgotten that discipline.

Attraversare le lingue è qualcosa che voi Italiani dovete fare per forza – per noi anglo-sassoni è una nuova esperienza – troppo volte aspettiamo che l’atro venga da noi invece di incontrarci a metà strada.

Nel frattempo, The Digital Humanist è un importante tentativo che attraversa Italiano e Inglese per invitarci tutti a dialogare.