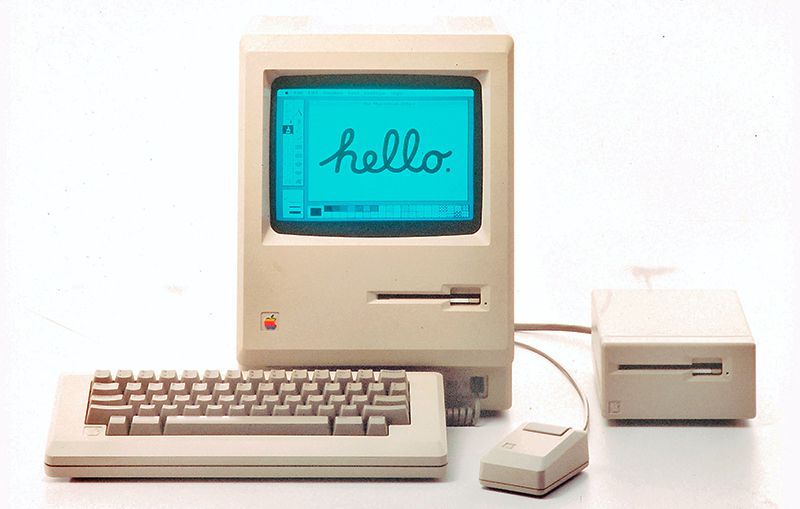

MacRumors has a story about how today is the 36th anniversary of the unveiling of the Macintosh. See 36 Years Ago Today, Steve Jobs Unveiled the First Macintosh. At the time I was working in Kuwait and had a Apple II clone. When a Macintosh came to a computer store I went down with a friend to try it. I must admit the Graphical User Interface (GUI) appealed to me immediately despite the poor performance. When I got back to Canada in 1985 to start graduate school I bought my first Macintosh, a 512K with a second disk drive. Later I hacked a RAM upgrade and got a small hard drive. Of course now I regret selling the computer to a friend in order to upgrade.

How Science Fiction Imagined the 2020s

What ‘Blade Runner,’ cyberpunk, and Octavia Butler had to say about the age we’re entering now

2020 is not just any year, but because it is shorthand for perfect vision, it is a date that people liked to imagine in the past. OneZero, a Medium publication has a nice story on How Science Fiction Imagined the 2020s (Jan. 17, 2020). The article looks at stories like Blade Runner (1982) that predicted what these years would be like. How accurate were they? Did they get the spirit of this age right? The author, Tim Maugham, reflects on why do many stories of the 1980s and early 1990s seemed to be concerned with many of the same issues that concern us now. He seems a similar concern with inequality and book/bust economies. He also sees sci-fi writers like Octavia Butler paying attention back then to climate change.

It was also the era when climate change started to make the news for the first time, and while it didn’t find its way into the public consciousness quickly enough, it certainly seemed to have grabbed the interest of science fiction writers.

Endgame for the Humanities?

The academic study of literature is no longer on the verge of field collapse. It’s in the midst of it. Preliminary data suggest that hiring is at an all-time low. Entire subfields (modernism, Victorian poetry) have essentially ceased to exist. In some years, top-tier departments are failing to place a single student in a tenure-track job.

The Chronicle Review has released a free collection on Endgame: Can Literary Studies Survive (PDF) Endgame is a collection of short essays about the collapse of literary studies in the US. The same is probably true of the other fields in the interpretative humanities and social sciences. This collection gives a human face to the important (and depressing) article Benjamin Schmidt wrote in The Atlantic about the decline in humanities majors since 2008, The Humanities Are In Crisis.

The Illusionistic Magic of Geometric Figuring

the purpose aimed at by Mantegna and Pozzo was not so much “to simulate stereopsis”—the process by which we see depth—but rather to achieve “a simulation of the perceptual effect of stereoptic vision.” Far from being visual literalists, these painters were literal illusionists—their aim was to make their audiences see something that wasn’t there.

CABINET has a nice essay by Margaret Wertheim connecting Bacon to Renaissance perspective to video games, The Illusionistic Magic of Geometric Figuring. Wertheim argues that starting with Roger Bacon there was a growing interest in the psychological power of virtual representation. Artists starting with Giotto in Assisi the Mantegna and later Pozzo created ever more perspectival representations that were seen as stunning at the time. (Pozzo painted the ceiling of St. Ignatius Being Received into Heaven in Sant’Ignazio di Loyola a Campo Marzio, Rome.)

The frescos in Assisi heralded a revolution both in representation and in metaphysical leaning whose consequences for Western art, philosophy, and science can hardly be underestimated. It is here, too, that we may locate the seed of the video gaming industry. Bacon was giving voice to an emerging view that the God of Judeo-Christianity had created the world according to geometric laws and that Truth was thus to be found in geometrical representation. This Christian mathematicism would culminate in the scientific achievements of Galileo and Newton four centuries later…

Wertheim connects this to the ever more immersive graphics of the videogame industry. Sometimes I forget just how far the graphics have come from the first immersive games I played like Myst. Whatever else some games do, they are certainly visually powerful. It often seems a shame to have to go on a mission rather than just explore the world represented.

There are 2,373 squirrels in Central Park. I know because I helped count them

I volunteered for the first squirrel census in the city. Here’s what I learned, in a nutshell.

From Lauren Klein on Twitter I learned about a great New York Times article on There are 2,373 squirrels in Central Park. I know because I helped count them. The article is by Denise Lau (Jan. 8, 2020.) As Klein points out, it is about the messiness of data collection. (Note that she has a book coming out on Data Feminism with Catherine D’Ignazio.)

Codecademy vs. The BBC Micro

The Computer Literacy Project, on the other hand, is what a bunch of producers and civil servants at the BBC thought would be the best way to educate the nation about computing. I admit that it is a bit elitist to suggest we should laud this group of people for teaching the masses what they were incapable of seeking out on their own. But I can’t help but think they got it right. Lots of people first learned about computing using a BBC Micro, and many of these people went on to become successful software developers or game designers.

I’ve just discovered Two-Bit History (0b10), a series of long and thorough blog essays on the history of computing by Sinclair Target. One essay is on Codecademy vs. The BBC Micro. The essay gives the background of the BBC Computer Literacy Project that led the BBC to commission as suitable microcomputer, the BBC Micro. He uses this history to then compare the way the BBC literacy project taught a nation (the UK) computing to the way the Codeacademy does now. The BBC project comes out better as it doesn’t drop immediately into drop into programming without explaining, something the Codecademy does.

I should add that the early 1980s was a period when many constituencies developed their own computer systems, not just the BBC. In Ontario the Ministry of Education launched a process that led to the ICON which was used in Ontario schools in the mid to late 1980s.

In 2020, let’s stop AI ethics-washing and actually do something – MIT Technology Review

But talk is just that—it’s not enough. For all the lip service paid to these issues, many organizations’ AI ethics guidelines remain vague and hard to implement.

Thanks to Oliver I came across this call for an end to ethics-washing by artificial intelligence reporter Karen Hao in the MIT Technology Review, In 2020, let’s stop AI ethics-washing and actually do something The call echoes something I’ve been talking about – that we need to move beyond guidelines, lists of principles, and checklists. She nicely talks about some of the initiatives to hold AI accountable that are taking place and what should happen. Read on if you want to see what I think we need.

The 100 Worst Ed-Tech Debacles of the Decade

With the end of the year there are some great articles showing up reflecting on debacles of the decade. One of my favorites is The 100 Worst Ed-Tech Debacles of the Decade. Ed-Tech is one of those fields where over and over techies think they know better. Some of the debacles Watters discusses:

- 3D Printing

- The “Flipped Classroom” (Full disclosure: I sat on a committee that funded these.)

- Op-Eds to ban laptops

- Clickers

- Stories about the end of the library

- Interactive whiteboards

- The K-12 Cyber Incident Map (Check it out here)

- IBM Watson

- The Year of the MOOC

This collection of 100 terrible ideas in instructional technology should be mandatory reading for all of us who have been keen on ed-tech. (And I am one who has develop ed-tech and oversold it.) Each item is a mini essay with links worth following.

From Facebook: An Update on Building a Global Oversight Board

We’re sharing the progress we’ve made in building a new organization with independent oversight over how Facebook makes decisions on content.

Brent Harris, Director of Governance and Global Affairs at Facebook has an interesting blog post that provides An Update on Building a Global Oversight Board (Dec. 12, 2019). Facebook is developing an independent Global Oversight Board which will be able to make decisions about content on Facebook.

I can’t help feeling that Facebook is still trying to avoid being a content company. Instead of admitting that parts of what they do matches what media content companies do, they want to stick to a naive, but convenient, view that Facebook is a technological facilitator and content comes from somewhere else. This, like the view that bias in AI is always in the data and not in the algorithms, allows the company to continue with the pretence that they are about clean technology and algorithms. All the old human forms of judgement will be handled by an independent GOB so Facebook doesn’t have to admit they might have a position on something.

What Facebook should do is admit that they are a media company and that they make decisions that influence what users see (or not.) They should do what newspapers do – embrace the editorial function as part of what it means to deal in content. There is still, in newspapers, an affectation to the separation between opinionated editorial and objective reporting functions, but it is one that is open for discussion. What Facebook is doing is a not-taking-responsibility, but sequestering of responsibility. This will allow Facebook to play innocent as wave after wave of fake news stories sweep through their system.

Still, it is an interesting response by a company that obviously wants to deal in news for the economic value, but doesn’t want to corrupted by it.

The weird, wonderful world of Y2K survival guides

The category amounted to a giant feedback loop in which the existence of Y2K alarmism led to more of the same.

Harry McCracken in Fast Company has a great article on The weird, wonderful world of Y2K survival guides: A look back (Dec. 13, 2019).The article samples some of the hype around the disruptive potential of the millenium. Particularly worrisome are the political aspects of the folly. People (again) predicted the fall of the government and the need to prepare for the ensuing chaos. (Why is it that some people look so forward to such collapse?)

Technical savvy didn’t necessarily inoculate an author against millennium-bug panic. Edward Yourdon was a distinguished software architect with plenty of experience relevant to the challenge of assessing the Y2K bug’s impact. His level of Y2K gloominess waxed and waned, but he was prone to declarations such as “my own personal Y2K plans include a very simple assumption: the government of the U.S., as we currently know it, will fall on 1/1/2000. Period.”

Interestingly, few people panicked despite all the predictions. Most people, went out and celebrated.

All of this should be a warning for those of us who are tempted to predict that artificial intelligence or social media will lead to some sort of disaster. There is an ethics to predicting ethical disruption. Disruption, almost by definition, never happens as you thought it would.