A Advanced Collaborative Support project that I was part of was funded, see HathiTrust Research Center Awards Three ACS Projects. Our project, called The Trace of Theory, sets out to first see if we can identify subsets of the HathiTrust volumes that are “theoretical” and then study try to track “theory” through these subsets.

Category: History of Computing and Multimedia

The computer program billed as unbeatable at poker

The Toronto Star has a nice story, The computer program billed as unbeatable at poker, about a poker playing program Cepehus that was developed at the Computer Poker Research here at the University of Alberta. Michael Bowling is quoted to the effect that,

No matter what you do, no matter how strong a player you are, even if you look at our strategy in every detail . . . there is no way you are going to be able of have any realistic edge on us.

On average we are playing perfectly. And that’s kind of the average that really matters.

You can play Cepehus at their web site. You can read their paper “Heads-up limit hold’em poker is solved”, just published in Science here (DOI: 10.1126/science.1259433).

UNIty in diVERSITY talk on “Big Data in the Humanities”

Last week I gave a talk for the UNIty in diVERSITY speaker series on “Big Data in the Humanities.” They have now put that up on Vimeo. The talk looked at the history of reading technologies and then some of the research at U of Alberta we are doing around issues of what to do with all that big data.

The future of the book: An essay from The Economist

The Economist has a nice essay on The future of the book. (Thanks to Lynne for sending this along.) The essay has three interfaces:

- A listening interface

- A remediated book interface where you can flip pages

- A scrolling interface

As much as we have moved beyond skeuomorphic interfaces that carry over design cues from older objects, the book interface is actually attractive. It suits the topic, which is captured in the title of the essay, “From Papyrus to Pixels: The Digital Transformation Has Only Just Begun.”

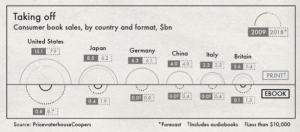

The content of the essay looks at how books have been remediated over time (from scroll to print) and then discusses the current shifts to ebooks. It points out that the ebook market is not like the digital music market. People still like print books and they don’t like to pick them apart like they do albums. The essay is particularly interesting on the self-publishing phenomenon and how authors are bypassing publishers and stores by publishing through Amazon.

The last chapter talks about audio books, one of the formats of the essay itself, and other formats (like treadmill forms that flash words at speed). This is where they get to the “transformation that has only just begun.”

Donkey Kong (Arcade) – The Cutting Room Floor

CONGRATULATION ! IF YOU ANALYSE DIFFICULT THIS PROGRAM,WE WOULD TEACH YOU.***** TEL.TOKYO-JAPAN 044(244)2151 EXTENTION 304 SYSTEM DESIGN IKEGAMI CO. LIM.

From Slashdot I learned about The Cutting Room Floor, a wiki “dedicated to unearthing and researching unused and cut content from video games.” For example, they have information about Donkey Kong (Arcade) that includes unused music, unused graphics, hidden text (see above), and regional difference. Yet another example of how the fan community is doing history of videogames in innovative ways.

We Have Never Been Digital

Historian of technology Thomas Haigh has written a nice reflection on the intersection of computing and the humanities, We Have Never Been Digital (PDF) (Communications of the ACM, 57:9, Sept 2014, 24-28). He gives a nice tour of the history of the idea that computers are revolutionary starting with Berkeley’s 1949 Giant Brains: Or Machines That Think. He talks about the shift to the “digital” locating it in the launch of Wired, Stewart Brand and Negroponte’s Being Digital. He rightly points out that the digital is not evenly distributed and that it has a material and analogue basis. Just as Latour argued that we have never been (entirely) modern, Haigh points out that we have never been and never will be entirely digital.

This leads to a critique of the “dated neologism” digital humanities. In a cute move he questions what makes humanists digital? Is it using email or building a web page? He rightly points out that the definition has been changing as the technology does, though I’m not sure that is a problem. The digital humanities should change – that is what makes disciplines vital. He also feels we get the mix of computing and the humanities wrong; that we should be using humanities methods to understand technology not the other way around.

There is a sense in which historians of information technology work at the intersection of computing and the humanities. Certainly we have attempted, with rather less success, to interest humanists in computing as an area of study. Yet our aim is, in a sense, the opposite of the digital humanists: we seek to apply the tools and methods of the humanities to the subject of computing…

On this I think he is right – that we should be doing both the study of computing through the lens of the humanities and experimenting with the uses of computing in the humanities. I would go further and suggest that one way to understand computing is to try it on that which you know and that is the distinctive contribution of the digital humanities. We don’t just “yack” about it, we try to “hack” it. We think-through technology in a way that should complement the philosophy and history of technology. Haigh should welcome the digital humanities or imagine what we could be rather than dismiss the field because we haven’t committed to only humanistic methods, however limited.

Haigh concludes with a “suspicion” I have been hearing since the 1990s – that the digital humanities will disappear (like all trends) leaving only real historians and other humanists using the tools appropriate to the original fields. He may be right, but as a historian he should ask why certain disciplines thrive and other don’t. I suspect that science and technology studies could suffer the same fate – the historians, sociologists, and philosophers could back to their homes and stop identifying with the interdisciplinary field. For that matter, what essential claim does any discipline have? Could history fade away because all of us do it, or statistics disappear because statistical techniques are used in other disciplines? Who needs math when everyone does it?

The use of computing in the other humanities is exactly why the digital humanities is thriving – we provide a trading zone for new methods and a place where they can be worked out across the concerns of other disciplines. Does each discipline have to work out how texts should be encoded for interchange and analysis or do we share enough to do it together under a rubric like computing in the humanities? As for changing methods – the methods definitive of the digital humanities that are discussed and traded will change as they get absorbed into other disciplines so … no, there isn’t a particular technology that is definitive of DH and that’s what other disciplines want – a collegial discipline from which to draw experimental methods. Why is it that the digital humanities are expected to be coherent, stable and definable in a way no other humanities discipline is?

Here I have to say that Matt Kirschenbaum has done us an unintentional disfavor by discussing the tactical use of “digital humanities” in English departments. He has led others to believe that there is something essentially mercenary or instrumental to the field that dirties it compared to the pure and uneconomical pursuit of truth to be found in science and technology studies, for example. The truth is that no discipline has ever been pure or entirely corrupt. STS has itself been the site of positioning at every university I’ve been at. It sounds from Haigh that STS has suffered the same trials of not being taken seriously by the big departments that humanities computing worried about for decades. Perhaps STS could partner with DH to develop a richer trading zone for ideas and techniques.

I should add that many of us are in DH not for tactical reasons, but because it is a better home to the thinking-through we believe is important than the disciplines we came from. I was visiting the University of Virginia in 2001-2 and participated in the NEH funded meetings to develop the MA in Digital Humanities. My memory is that when we discussed names for the programme it was to make the field accessible. We were choosing among imperfect names, none of which could ever communicate the possibilities we hoped for. At the end it was a choice as to what would best communicate to potential students what they could study.

The Material in Digital Books

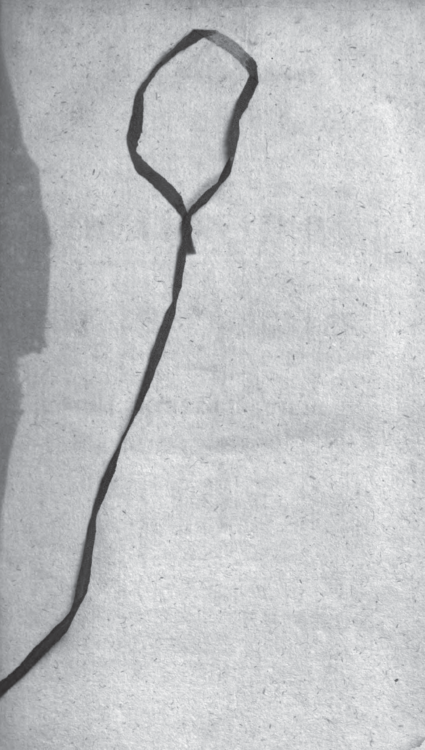

Elika Ortega in a talk at Experimental Interfaces for Reading 2.0 mentioned two web sites that gather interesting material traces in digital books. One is The Art of Google Books that gathers interesting scans in Google Books (like the image above).

The other is the site Book Traces where people upload interesting examples of marginal marks. Here is their call for examples:

Readers wrote in their books, and left notes, pictures, letters, flowers, locks of hair, and other things between their pages. We need your help identifying them because many are in danger of being discarded as libraries go digital. Books printed between 1820 and 1923 are at particular risk. Help us prove the value of maintaining rich print collections in our libraries.

Book Traces also has a Tumblr blog.

Why are these traces important? One reason is that they help us understand what readers were doing and think while reading.

Replaying Japan 2014

Last week we organized Replaying Japan 2014 here in Edmoton. This was the second international conference on Japanese game studies and the third event we co-organized with the Ritsumeikan Center for Game Studies (in Japanese with English pamphlet).

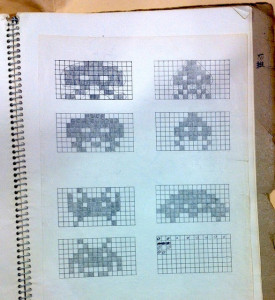

The opening keynote was by Tomohiro Nishikado, the designer of Space Invaders – the 1978 game that launched specialty arcades in Japan. He talked about the design process and showed his notebooks which he had brought. Here you can see the page on his notebook with the sketches of the aliens and then the bitmap versions. I kept my conference notes on his talk and others here.

The conference was a huge success with over 100 attendees from 6 countries and over 20 universities. We had people from industry, academia and government too. We had a significant number of Japanese speakers despite English being the language of the conference. After the conference we met to plan for next year’s conference in Kyoto. See you there!

This conference was supported by the Japan Foundation, the GRAND Network of Centres of Excellence, the Prince Takamado Centre, the Ritsumeikan Center for Game Studies, CIRCA, and the University of Alberta.

The Amiga Lounge

From Slashdot I came across a site on the Amiga called the The Amiga Lounge. On the site they have a story on The Almost forgotten Story of the Amiga 2000. The 2000 isn’t a favorite for collection, but it was the machine that took the Video Toaster card which made video editing and effects possible on the Amiga before other personal computers.

AMICO dissolved

I just discovered (about 9 years after the fact) that The Art Museum Image Consortium (AMICO) was dissolved in 2005. For a while AMICO seemed to be one of the major art historical image banks for teaching and research. Now they are gone, though they have kept a web site for archival purposes (see screenshot of entry web page above.)

I have written before about digital centres that have closed down, AMICO isn’t an example of a centre, but it was an important project which is now gone. I can’t find any discussion about the dissolution, but will look. In general, I think we need to learn from the passing of projects.