Computational propaganda is ubiquitous, researchers say. But the field of psychology aims to help.

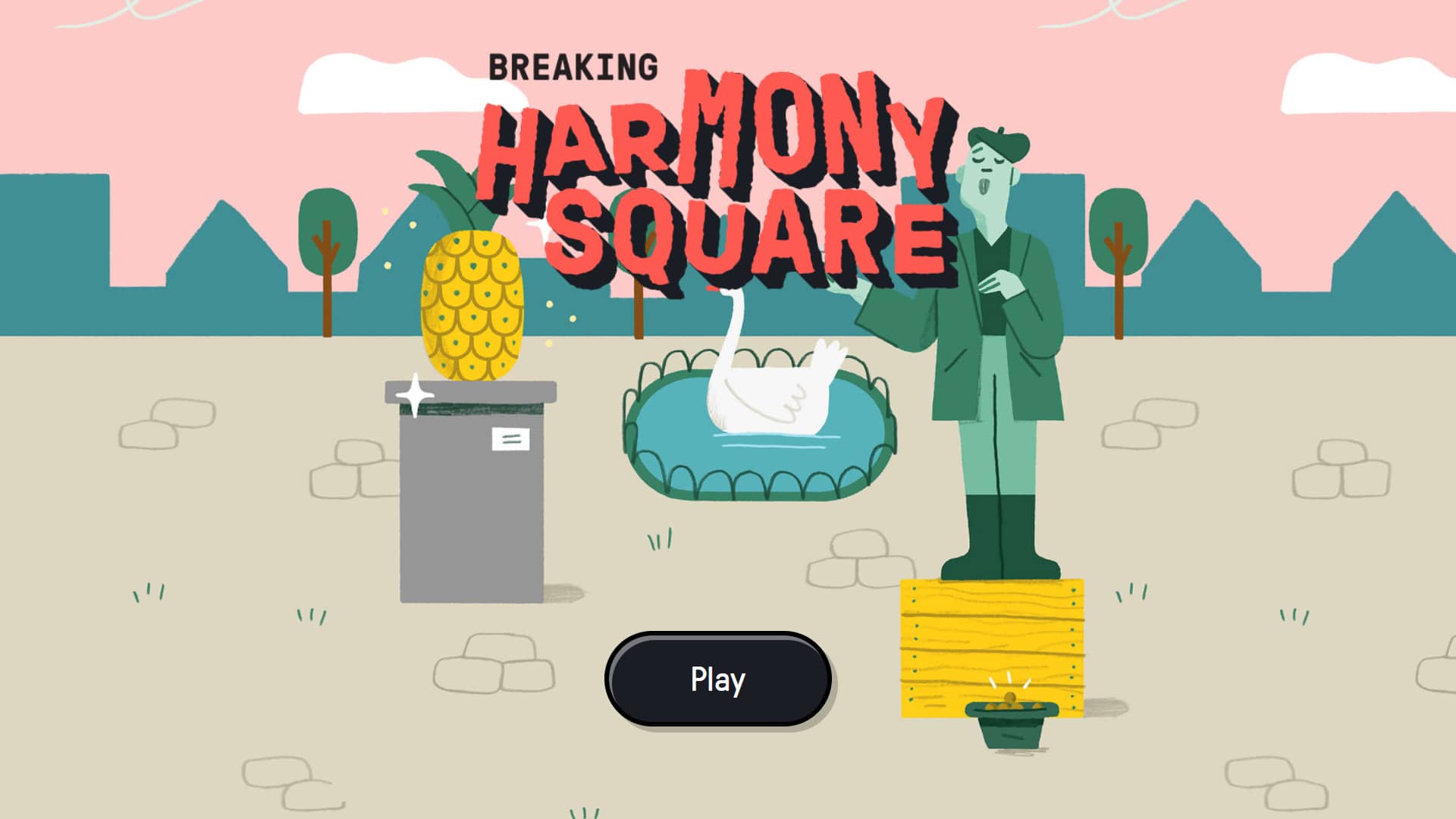

Undark has a fascinating article by Teresa Carr about using games to inoculate people against trolling and mininformation, Psychology, Misinformation, and the Public Square (May 3, 2021). The game is Breaking Harmony Square and the idea is to troll a community.

What’s the game like? The game feels like a branching, choose-your-own-adventure under the hood where a manager walks you through what might do or not and then complements you when you are a good troll. There is a ticker so you can see the news about Harmony Square. It feels a bit pedantic when the managerial/editorial voice says things like “Kudos for paying attention to buzzwords. You ignored the stuff that isn’t emotionally manipulative.” Still, the point is to understand what can be done to manipulate a community so that you are inoculated against it.

An important point made by the article is that games, education and other interventions are not enough. Drvier’s education is only part of safe roads. Laws and infrastructure are also important.

I can’t help feeling that we are repeating a pattern of panic and then literacy proposals in the face of new media politics. McLuhan drew our attention to manipulation by media and advertising and I remember well intentioned classes on reading advertising like this more current one. Did they work? Will misinformation literacy work now? Or, is the situation more complex with people like Trump willing to perform convenient untruths?

Whatever the effectiveness of games or literacy training, it is interesting how “truth” has made a comeback. At the very moment when we seem to be witnessing the social and political construction of knowledge, we are hearing calls for truth.