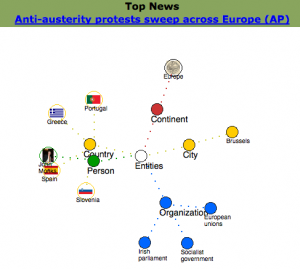

Jon pointed me to an online and illustrated essay Books in the Age of the iPad by Craig Mod that makes an interesting argument about the relative uses of digital reading devices like the iPad. He argues that there are two broad groups of content:

- Formless Content which doesn’t have a well-defined form. This sort of content can be easily poured into new bottles from iPhones to iPads. It doesn’t matter what form you read it in. (The illustration above is meant to suggest that such content can be poured into print, screen, or moble.)

- Definite Content which does have a definite form. The form for such works matters to the content so you can’t easily pour it into a new form. Such content could be designed to be viewed on an interactive screen (and hence it would be awkward to pour it onto print) or it could be designed to be read in paperback (and hence it would be awkward to read it on the screen.)

Mod argues that we should start moving Formless Content to digital devices and in the case of Definite Content we should be willing to leave it on the platform it was designed for. Thus art books should stay on paper while cheap novels should be available also in digital forms for mobile reading.

Contrast this to Dale Salwak’s To every page, turn, turn, turn (Times Higher Education, Sept. 2, 2010), an online essay with the Times Higher Education bemoaning the loss of “deep reading.” I have no problem with Salwak’s defense of reading and the reading of books, but I’m not sure that there is anything inherently “deep” about books unless by deep he means longer (than essays on the web.) I don’t see why one can’t have a quiet, deep, reading experience off an iPad, though the argument might be made that the iPad has more distractions available. He ends with an argument I haven’t heard before – that books can be your friends (when you don’t have any?)

We all know that a love for books usually starts early in life. If our students come from homes where the predominant sound is the turning of pages, then from our experiences they will hear an affirmation of their own; if, on the other hand, they come from homes in which books are rarely seen, never talked about and seldom read, they may in time feel angry or cheated by their intellectual void. It is our task as educators and adults to provide a model for the reading life and the rewards and insights it can yield.

“Hold on to your books,” I say. “They will help you through. Let them be your best friend, and they will remain a solace in your life as they continue to be in mine.”

Of course today youth find false friends online not between the covers.