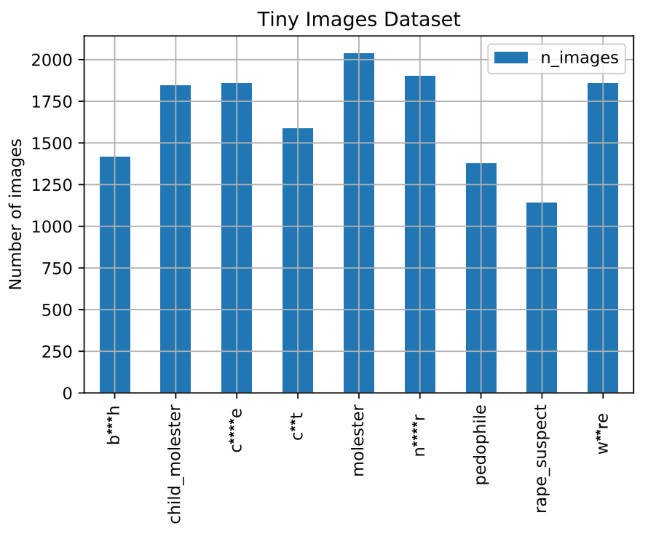

Vinay Prabhu, chief scientist at UnifyID, a privacy startup in Silicon Valley, and Abeba Birhane, a PhD candidate at University College Dublin in Ireland, pored over the MIT database and discovered thousands of images labelled with racist slurs for Black and Asian people, and derogatory terms used to describe women. They revealed their findings in a paper undergoing peer review for the 2021 Workshop on Applications of Computer Vision conference.

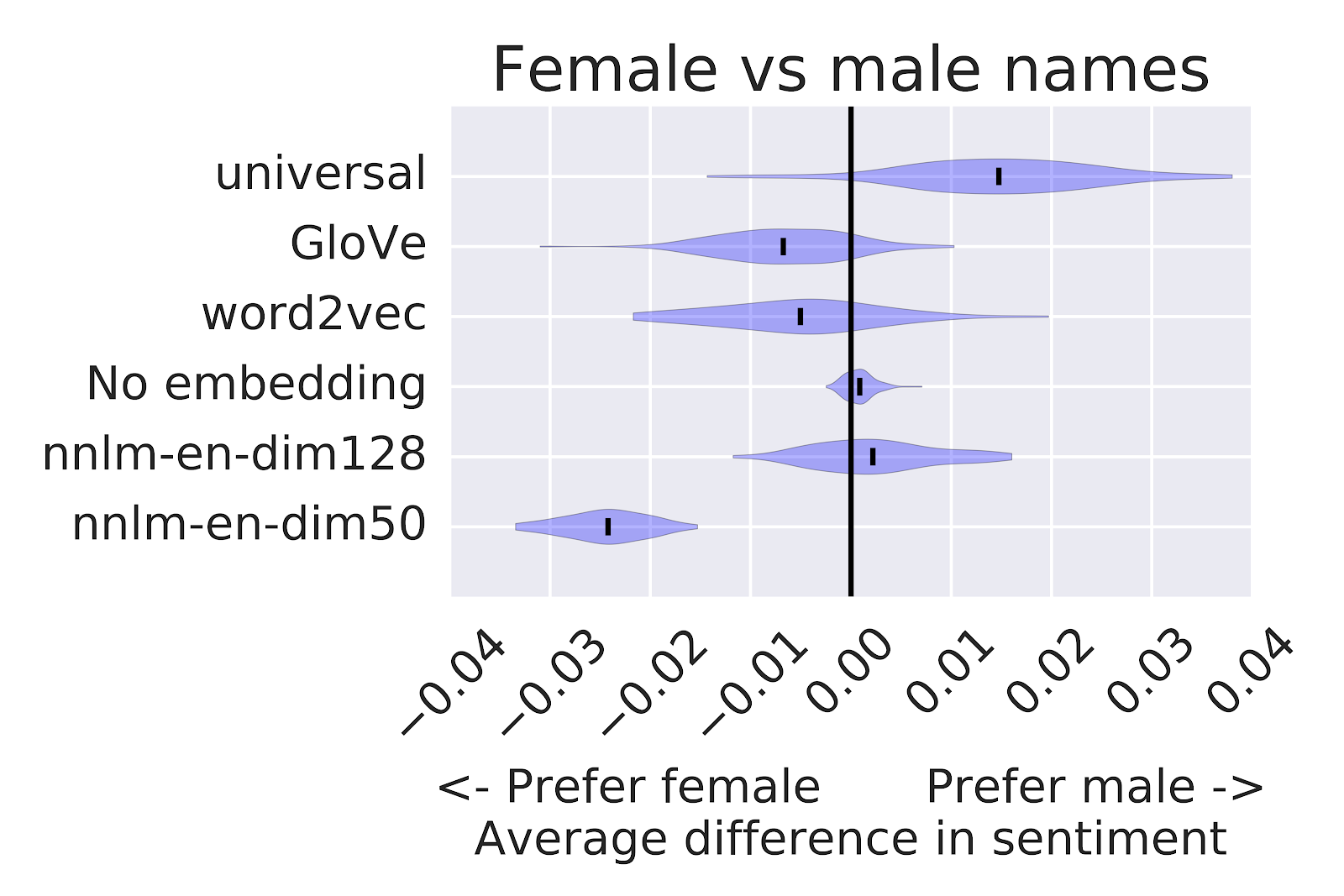

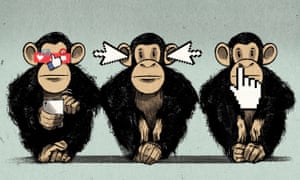

Another one of those “what were they thinking when they created the dataset stories” from The Register tells about how MIT apologizes, permanently pulls offline huge dataset that taught AI systems to use racist, misogynistic slurs. The MIT Tiny Images dataset was created automatically using scripts that used the WordNet database of terms which itself held derogatory terms. Nobody thought to check either the terms taken from WordNet or the resulting images scoured from the net. As a result there are not only lots of images for which permission was not secured, but also racists, sexist, and otherwise derogatory labels on the images which in turn means that if you train an AI on these it will generate racist/sexist results.

The article also mentions a general problem with academic datasets. Companies like Facebook can afford to hire actors to pose for images and can thus secure permissions to use the images for training. Academic datasets (and some commercial ones like the Clearview AI database) tend to be scraped and therefore will not have the explicit permission of the copyright holders or people shown. In effect, academics are resorting to mass surveillance to generate training sets. One wonders if we could crowdsource a training set by and for people?