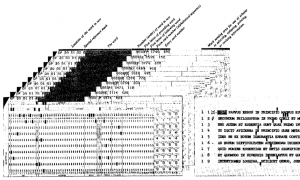

I came across a 1957 article by an IBM scientist, P. Tasman on the methods used in Roberto Busa’s Index Thomisticus project, with the title Literary Data Processing (IBM Journal of Research and Development, 1(3): 249-256.) The article, which is in the third issue of the IBM Journal of Research and Development, has an illustration of how they used punch cards for this project.

While the reproduction is poor, you can read the things encoded on the card for each word:

- Location in text

- Special reference mark

- Word

- Number of word in text

- First letter of preceding word

- First letter of following word

- Form card number

- Entry card number

At the end Tasman speculates on how these methods developed on the project could be used in other areas:

Apart from literary analysis, it appears that other areas of documentation such as legal, chemical, medical, scientific, and engineering information are now susceptible to the methods evolved. It is evident, of course, that the transcription of the documents in these other fields necessitates special sets of ground rules and codes in order to provide for information retrieval, and the results will depend entirely upon the degree and refinement of coding and the variety of cross referencing desired.

The indexing and coding techniques developed by this method offer a comparatively fast method of literature searching, and it appears that the machine-searching application may initiate a new era of language engineering. It should certainly lead to improved and more sophisticated techniques for use in libraries, chemical documentation, and abstract preparation, as well as in literary analysis.

Busa’s project may have been more than just the first humanities computing project. It seems to be one of the first projects to use computers in handling textual information and a project that showed the possibilities for searching any sort of literature. I should note that in the issue after the one in which Tasman’s article appears you have an article by H. P. Luhn (developer of the KWIC) on A Statistical Approach to Mechnized Encoding and Searching of Literary Information. (IBM Journal of Research and Development 1(4): 309-317.) Luhn specifically mentions the Tasman article and the concording methods developed as being useful to the larger statistical text mining that he proposes. For IBM researchers Busa’s project was an important first experiment handling unstructured text.

I learned about the Tasman article in a journal paper deposited by Thomas Nelson Winter on Roberto Busa, S.J., and the Invention of the Machine-Generated Concordance. The paper gives an excellent account of Busa’s project and its significance to concording. Well worth the read!