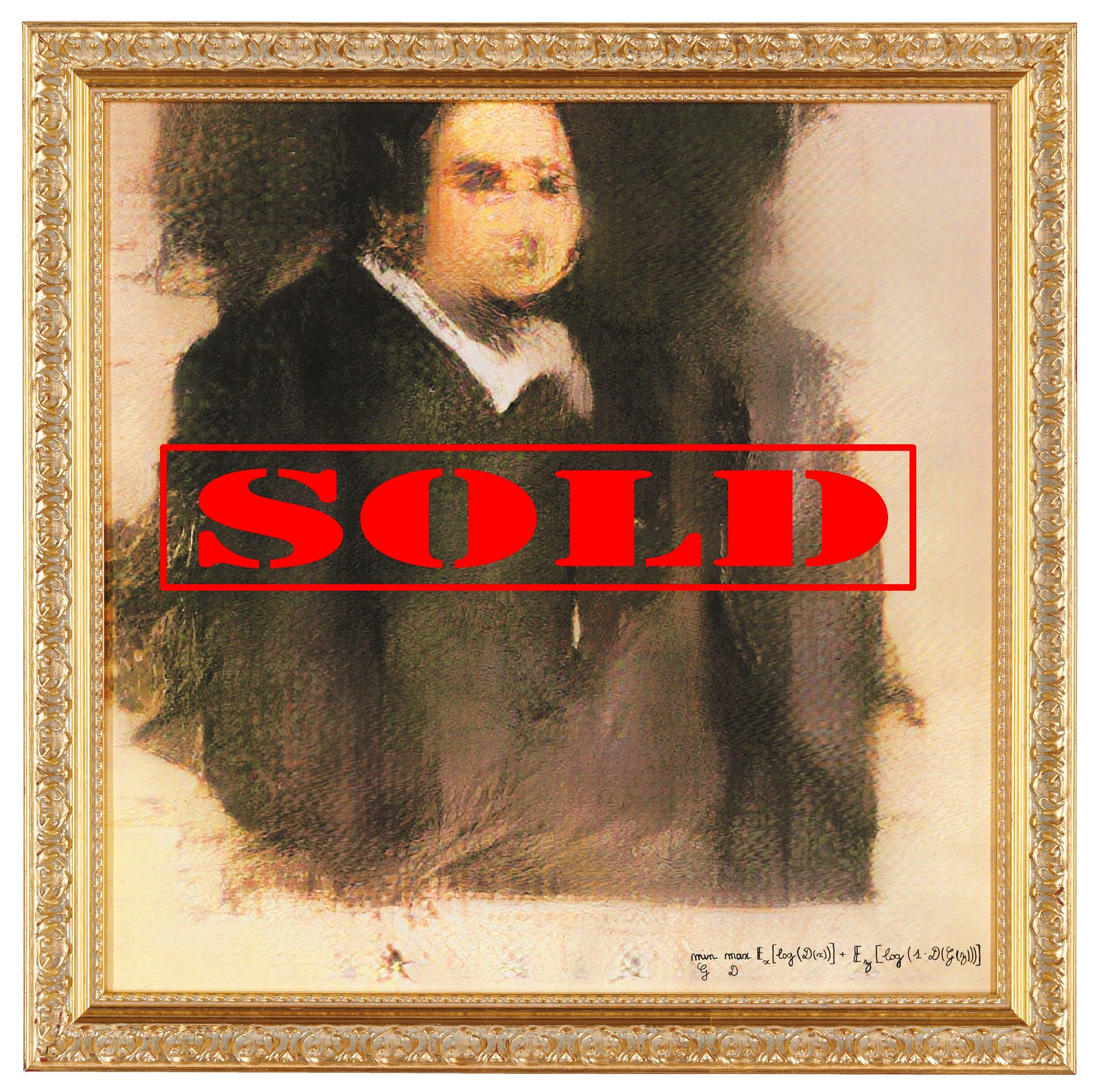

Seen in the wild, robots often appear cute and nonthreatening. This doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be hostile.

Wired magazine has a nice short piece that suggests, Of Course Citizens Should Be Allowed to Kick Robots. In some ways the point of the essay is not how to treat robots, but whether we should tolerate these surveillance robots on our sidewalks.

Blanket no-punching policies are useless in a world full of terrible people with even worse ideas. That’s even more true in a world where robots now do those people’s bidding. Robots, like people, are not all the same. While K5 can’t threaten bodily harm, the data it collects can cause real problems, and the social position it puts us all in—ever suspicious, ever watched, ever worried about what might be seen—is just as scary. At the very least, it’s a relationship we should question, not blithely accept as K5 rolls by.

The question, “Is it OK to kick a robot?” is a good one that nicely brings the ethics of human-robot co-existence down to earth and onto our side walks. What sort of respect do the proliferation of robots and scooters deserve? How should we treat these stupid things when enter our everyday spaces?