The Digging Into Data program commissioned CLIR (Council on Library and Information Resources) to study and report on the first round of the programme. The report includes case studies on the 8 initial projects including one on our Criminal Intent project that is titled Using Zotero and TAPOR on the Old Bailey Proceedings: Data Mining with Criminal Intent (DMCI). More interesting are some of the reflections on big data and research in the humanities that the authors make:

1. One Culture. As the title hints, one of the conclusions is that in digital research the lines between disciplines and sectors have been blurred to the point where it is more accurate to say there is one culture of e-research. This is obviously a play on C. P. Snow’s Two Cultures. In big data that two cultures of the science and humanities, which have been alienated from each other for a century or two, are now coming back together around big data.

Rather than working in silos bounded by disciplinary methods, participants in this project have created a single culture of e-research that encompasses what have been called the e-sciences as well as the digital humanities: not a choice between the scientific and humanistic visions of the world, but a coherent amalgam of people and organizations embracing both. (p. 1)

2. Collaborate. A clear message of the report is that to do this sort of e-research people need to learn to collaborate and by that they don’t just mean learning to get along. They mean deliberate collaboration that is managed. I know our team had to consciously develop patterns of collaboration to get things done across 3 countries and many more universities. It also means collaborating across disciplines and this is where the “one culture” of the report is aspirational – something the report both announces and encourages. Without saying so, the report also serves as a warning that we could end up with a different polarization just as the separation of scientific and humanistic culture is healed. We could end up with polarization between those who work on big data (of any sort) using computational techniques and those who work with theory and criticism in the small. We could find humanists and scientists who use statistical and empirical methods in one culture while humanists and scientists who use theory and modelling gather as a different culture. One culture always spawns two and so on.

3. Expand Concepts. The recommendations push the idea that all sorts of people/stakeholders need to expand their ideas about research. We need to expand our ideas about what constitutes research evidence, what constitutes research activity, what constitutes research deliverables and who should be doing research in what configurations. The humanities and other interpretative fields should stop thinking of research as a process that turns the reading of books and articles into the writing of more books and articles. The new scale of data calls for a new scale of concepts and a new scale of organization.

It is interesting how this report follows the creation of the Digging Into Data program. It is a validation of the act of creating the programme and creating it as it was. The funding agencies, led by Brett Bobley, ran a consultation and then gambled on a programme designed to encourage and foreground certain types of research. By and large their design had the effect they wanted. To some extent CLIR reports that research is becoming what Digging encouraged us to think it should be. Digging took seriously Greg Crane’s question, “what can you do with a million books”, but they abstracted it to “what can you do with gigabytes of data?” and created incentives (funding) to get us to come up with compelling examples, which in turn legitimize the program’s hypothesis that this is important.

In other words we should acknowledge and respect the politics of granting. Digging set out to create the conditions where a certain type of research thrived and got attention. The first round of the programme was, for this reason, widely advertised, heavily promoted, and now carefully studied and reported on. All the teams had to participate in a small conference in Washington that got significant press coverage. Digging is an example of how granting councils can be creative and change the research culture.

The Digging into Data Challenge presents us with a new paradigm: a digital ecology of data, algorithms, metadata, analytical and visualization tools, and new forms of scholarly expression that result from this research. The implications of these projects and their digital milieu for the economics and management of higher education, as well as for the practices of research, teaching, and learning, are profound, not only for researchers engaged in computationally intensive work but also for college and university administrations, scholarly societies, funding agencies, research libraries, academic publishers, and students. (p. 2)

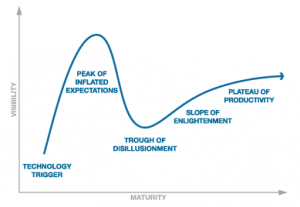

The word “presents” can mean many things here. The new paradigm is both a creation of the programme and a result of changes in the research environment. The very presentation of research is changed by the scale of data. Visualizations replace quotations as the favored way into the data. And, of course, granting councils commission reports that re-present a heady mix of new paradigms and case studies.