Peter Organsciak has created a new version of TAToo.

To try to set your own up see, Setup you TAToo.

Peter Organsciak has created a new version of TAToo.

To try to set your own up see, Setup you TAToo.

I am at ITSEE in Birmingham at a workshop on tools and collaboration. See my Conference Report, Tools For Collaborative Scholarly Editing Over The Web.

There is a lot of talk about ontologies and interoperation of tools.

Stephen Ramsay sent me one of my first Python programs that I wrote in response to his telling me about Perl poems. No doubt I was also influenced by Jerry McGann and his ideas on deformation.

#!/usr/bin/python

import random

def Random_Means(Words):

return random.randrange(len(Words))

How_Much = ["How much", "All", "Some", "Every", "The", "No"]

Of_What = ["interpretation", "rhetoric", "fiction", "fabrication",

"deformation","representation"]

Could_Be = ["could be", "was", "is", "will be", "would be"]

At_End = [".", "!", "?"]

All = Of_What[Random_Means(Of_What)]

Interpretation = Could_Be[Random_Means(Could_Be)]

Is = How_Much[Random_Means(How_Much)]

Just = Of_What[Random_Means(Of_What)]

Deformation = At_End[Random_Means(At_End)]

print Is + " " + All + " " + Interpretation + " " + Just + Deformation #?

This playful exercise then led to Untitled #4 which led to our dialogue with the same name which led to the Animation!

Stan sent me a link to this blog about information and visualization, Information Is Beautiful. Take, for example, The Billion Dollar Gram which shows and compares things that billions of dollars are being spent on.

Not long ago I blogged about death and your online identity. Now I’ve come across a service called SlightlyMorbid which will send prepared messages to contacts when they are contacted by a trusted party. It is a sort of dead-man’s switch for a bunch of last emails to your online friends who wouldn’t otherwise hear of your death. Great name for a service, though.

Peter sent me a link to Mozilla Labs Jetpack, a project to develop a way that makes it easy for people to extend the power of their browsers using Javascript. It strikes me that there is a desire and need for an easy programming extension that provides, as HyperCard did years ago, a way for amateurs to extend their environment with widgets. Widgets, gadgets, and other small utilities have their place, but we need a common ground for them for the paradigm to take off.

Back to Pontypool, the semiotic zombie movie that has infected me. The image above is of the poster for the missing cat Honey that seems to have something to do with the start of the semiotic infection. The movie starts with Grant Mazzy’s voice over the radio talking about,

Mrs French’s cat is missing. The signs are posted all over town. Have you seen Honey? Well, we have all seen the posters, but nobody has seen Honey the cat. Nobody, until last Thursday morning when Miss Collettepiscine … (drove off the bridge to avoid the cat)

He goes on to pun on “Pontypool” (the name of the town the movie takes place in), Miss Collettepiscine’s name (French for “panty-pool”), and the local name of the bridge she drove off. He keeps repeating variations of Pontypool a hint at the language virus to come.

As for the language virus, I replayed parts of the movie where they talk about it. At about 58 minutes in they hear the character Ken clearly get infected and begin to repeat himself as they talk on the cellphone. Dr. Mendez concludes, “That’s it, he is gone. He is just a crude radio signal, seeking.” A little later Mendez gets it and proposes,

Mendez: No … it can’t be, it can’t be. It’s viral, that much is clear. But not of the blood, not of the air, not on or even in our bodies. It is here.

Grant: Where?

Mendez: It is in words. Not all words, not all speaking, but in some. Some words are infected. And it spreads out when the contaminated word is spoken. Ohhhh. We are witnessing the emergence of a new arrangement for life … and our language is its host. It could have sprung spontaneously out of a perception. If it found its way into language it could leap into reality itself, changing everything. It may be boundless. It may be a God bug.

Grant: OK, Dr. Mendez. Look, I don’t even believe in UFOs, so I … I’ve got to stop you there with that God bug thing.

Mendez: Well that is very sensible because UFOs don’t exist. But I assure you, there is a monster loose and it is bouncing through our language, frantically trying to keep its host alive.

Grant: Is this transmission itself … um …

Mendez: No, no, no, no. If the bug enters us, it does not enter by making contact with our eardrum. It enters us when we hear the word and we understand it. Understand?

It is when the word is understood that the virus takes hold. And it copies itself in our understanding.

Grant: Should we be … talking about this?

Sydney: What are we talking about?

Grant: Should we be talking at all?

Mendez: Well, to be safe, no, probably not. Talking is risky, and well, talk radio is high risk. And so … we should stop.

Grant: But, we need to tell people about this. People need to know. We have to get this out.

Mendez: Well it’s your call Mr Mazzy. But let’s just hope that your getting out there doesn’t destroy your world.

As one thoughtful review essay points out, Pontypool is not the first to play with the meme of information viruses that can infect us. Snow Crash, the Stephenson novel which features a language-virus, even appears in the movie.

Pontypool itself is infectious, morphing from form to form. Sequels are threatened. The book, Pontypool Changes Everything, which starts with a character who keeps Ovid’s Metamorphoses in his, led to the movie which led to the radio play which was created by re-editing the movie audio (and it apparently has a different ending with “paper”.)

Thanks to readers for pointing out the spam you are getting when you read my blog with the Google Reader. I’m trying to fix the problem. If you have links to good explanations of the problem please email me.

Stan pointed me to a neat circular visualization tool, Circos – visualize genomes and genomic data. As the site title says, Circos is for visualizing genomic information, but the circular model strikes me a applicable to other domains. In fact, Camilo Arango in Computing Science, just defended a MSc thesis on a Course Browser design that uses a circular design to show requisites between courses. While the circular design is attractive, I wonder if it is misleading for linear information, like a text, if one wraps the text around the edge of the circle, the way TextArc does.

The Circos site has an interesting slide show on visualizing quantitative information by Martin Krzywinski that starts with Tufte and then shows different genomic visualization models leading up to Circos.

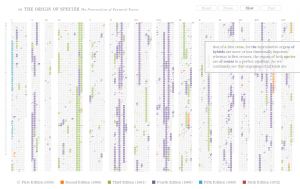

Sean pointed me to a lovely visualization by Ben Fry called The Preservation Of Favoured Traces. The animated visualization shows the edits of Darwin’s The Origin Of Species edition by edition. It is a rich-prospect view of the entire work with color coded lines where changes were made. It was developed in Processing. Ben Fry says the following about the project:

We often think of scientific ideas, such as Darwin’s theory of evolution, as fixed notions that are accepted as finished. In fact, Darwin’s On the Origin of Species evolved over the course of several editions he wrote, edited, and updated during his lifetime. The first English edition was approximately 150,000 words and the sixth is a much larger 190,000 words. In the changes are refinements and shifts in ideas — whether increasing the weight of a statement, adding details, or even a change in the idea itself.