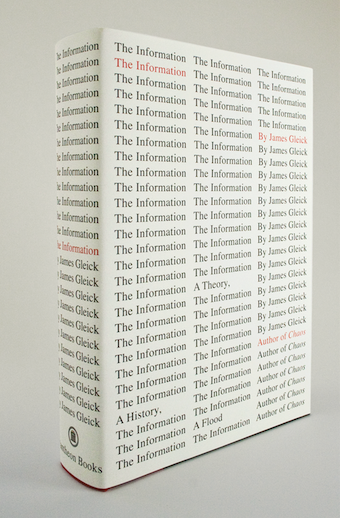

I just finished Jame Gleick’s The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood. One of the best books I’ve read in some time. Despite its length (527 pages including index, bibliography and notes) it doesn’t exhaust the subject pedantically. Many of the chapters hint and more things to think about. It also takes an unexpected trajectory. I expected it to go from Babbage and the telegraph to computers and then Engelbart and information extensions. Instead he works his way through physics and math. He looks at ideas about how to measure information and the materiality of information explaining the startling conclusion that “Forgetting takes work.” (p. 362)

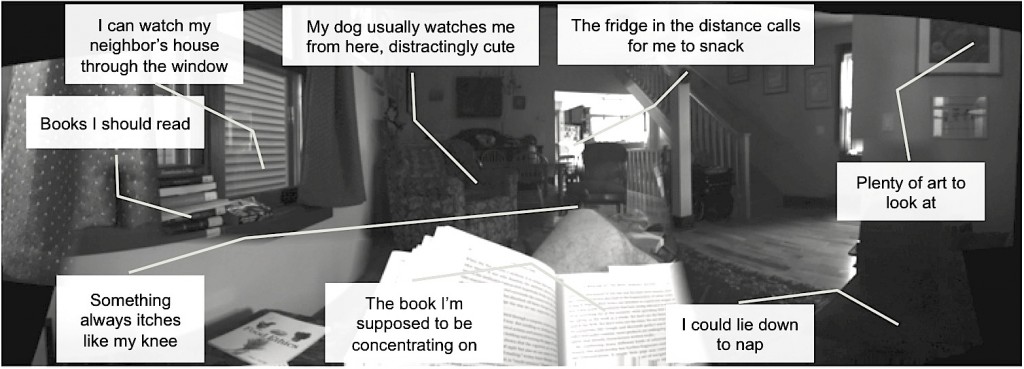

The second to last chapter “News News Every Day” is as good an exploration of the issue of information overload as I have read. He suggests that the perception of “overload” comes from the metaphoric application of our understanding of electrical circuits as in “overloading the circuits.” If one believes the nervous system is like an electrical network then it is possible to overload the network with too much input. That, after all, is what Carr argues in The Shallows (though he uses cognitive science.) None-the-less electrical and now computing metaphors for the mind and nervous system are haunting the discussion about information. Is one overloaded with information when you turn a corner in the woods and see a new vista of lakes and mountains? What Gleick does is connect information overload with the insight that it is forgetting that is expensive. We feel overloaded because it takes work not to find information, but to filter out information. To have peaceful moment thinking you need to forget and that is expensive.

Gleick ends, as he should, with meaning. Information theory ignores meaning, but information is not informative unless it means something to someone at some time. Where does the meaning come from? Is it interconnectedness? Does the hypertext network (and tools that measure connectedness like Google) give meaning to the data? No, for Gleick it is human choice.

As ever, it is the choice that informs us (in the original sense of that word). Selecting the genuine takes work; then forgetting takes even more work. (p. 425)