From Twitter I learned about this list of cultural Non-profit crowdsourcing projects. I’m amazed there are so few, but some of that is that many projects are probably not listed, or failed early on.

No girls allowed

I’ve been meaning to blog about a nice feature in Polygon, No girls allowed. The essay starts by talking about gendered toys (and toy store aisles) and then moves on to why there isn’t the same gendering in games, but worse:

As for the boys section — there isn’t one. Everything else is for boys.

If the selection at the average retailer is anything to go by, girls don’t play video games. If cultural stereotypes are anything to go by, video games are for males. They’re the makers, the buyers and the players.

It has been fashionable to point to statistics that suggest “forty-five percent of all game players are women.” (Entertainment Software Association Industry Facts) Such facts, however, apply to all games, but not necessarily to retail games which are marketed more to males. The essay therefore looks at marketing and the vicious cycle of designing for a market (young men) that then reinforces beliefs about the market (it is best to target young men.)

According to Roeser, it makes sense from a marketing perspective for the video game industry to have pursued a male audience, which is exactly what it did starting in the early ’90s.

Tracey Lien then looks back at the history of game marketing and notes how it is only recently that there has been such market segmentation. Lien writes about early women developers like Carol Shaw who worked for Atari and how they weren’t designing for a particular gender.

Things changed in the mid 1980s after the Atari crash. Nintendo saved the industry by reintroducing games as toys which were then marketed as toys. Nintendo started gathering demographic information and discovered that more boys were playing which then fed into segmentation.

In the 1990s, the messaging of video game advertisements takes a different turn. Television commercials for the Game Boy feature only young boys and teenagers. The ad for the Game Boy Color has a boy zapping what appears to be a knight with a finger laser. Atari filmed a bizarre series of infomercials that shows a man how much his life will improve if he upgrades to the Jaguar console. With each “improvement,” he has more and more attractive women fawning over him. There is nothing in any of the ads that indicate that the consoles and games are for anyone other than young men.

The marketing segmentation became a “self-fulfilling prophecy” that ignored all the games popular with women like Myst and the Sims. The marketing and media present the male oriented games as the important or real games and the others as exceptions. Perhaps Grand Theft Auto is the exception and Farmville is the norm. Perhaps retail console games are just a fraction of game culture.

This essay strikes me as a great entry into talking about gender and games for a course. I also like the web design with the images that alternate from one side to the other.

On a related note, see the Let Toys Be Toys (for Girls and Boys) advocacy web site.

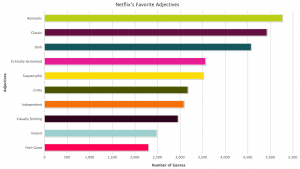

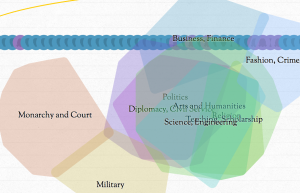

How Netflix Reverse Engineered Hollywood

Alexis C. Madrigal has a fine article in The Atlantic on How Netflix Reverse Engineered Hollywood (Jan. 2, 2014). The article moves from an interesting problem about Netflix’s micro-genres, to text analysis of results of a scrape, to reverse engineering the Netflix algorithm, to creating a genre generator (at the top of the article) and then to an interview with the Netflix VP of Product who was responsible for the tagging system. It is a lovely example of thinking through something and using technology when needed. The text analysis isn’t the point, it is a tool to use in understanding the 76,897 micro-genres uncovered. (Think about it … Netflix has over 70,000 genres of movies and TV shows, some with no actual movies or shows as examples of the micro-genre.)

Madrigal goes on to talk about the procedure Netflix uses to create genres and use them in recommending shows. It turns out to be a combination of content analysis (actual humans watching a movie/show and ranking it in various ways) and automatic methods that combine tags. This combination of human and machine methods is also the process Madrigal describes for his own pursuit of Netflix genres. It is another sense of humanities computing – those procedures that involve both human and algorithmic interventions.

The post ends with an anomaly that illustrates the hybridity of procedure. It turns out the most named actor is Raymond Burr of Perry Mason. Netflix has a larger number of altgenres with Raymond Burr than anyone else. Why would he rank so high in micro-genres? Madrigal tries a theory as to why this is that is refuted by the VP Yellin, but Yellin can’t explain the anomaly either. As Madrigal points out, in Perry Mason shows the mystery is always resolved by the end, but in the case of the mystery of Raymond Burr in genre, there is no revealing bit of evidence that helps us understand how he rose in the ranks.

On the other hand, no one — not even Yellin — is quite sure why there are so many altgenres that feature Raymond Burr and Barbara Hale. It’s inexplicable with human logic. It’s just something that happened.

I tried on a bunch of different names for the Perry Mason thing: ghost, gremlin, not-quite-a-bug. What do you call the something-in-the-code-and-data which led to the existence of these microgenres?

The vexing, remarkable conclusion is that when companies combine human intelligence and machine intelligence, some things happen that we cannot understand.

“Let me get philosophical for a minute. In a human world, life is made interesting by serendipity,” Yellin told me. “The more complexity you add to a machine world, you’re adding serendipity that you couldn’t imagine. Perry Mason is going to happen. These ghosts in the machine are always going to be a by-product of the complexity. And sometimes we call it a bug and sometimes we call it a feature.”

Perhaps this serendipity is what is original in the hybrid procedures involving human practices and algorithms? For some these anomalies are the false positives that disrupt big data’s certainty, for others they are the other insight that emerges from the mixing of human and computer processes. As Madrigal concludes:

Perry Mason episodes were famous for the reveal, the pivotal moment in a trial when Mason would reveal the crucial piece of evidence that makes it all makes sense and wins the day.

Now, reality gets coded into data for the machines, and then decoded back into descriptions for humans. Along the way, humans ability to understand what’s happening gets thinned out. When we go looking for answers and causes, we rarely find that aha! evidence or have the Perry Mason moment. Because it all doesn’t actually make sense.

Netflix may have solved the mystery of what to watch next, but that generated its own smaller mysteries.

And sometimes we call that a bug and sometimes we call it a feature.

We need to talk about TED by Benjamin Bratton

The Guardian has reprinted the trasnscript of Benjamin Bratton’s We need to talk about TED talk that is critical of TED. He looks at each of the three terms in T.E.D. (Technology, Entertainment, Design) and here is paraphrase of some of his points:

- TED talks conceptualize the future, but tend to oversimplify it.

- TED wants to be about imagining the future, but it tends to promote placebo politics and technology.

- We are told that change is accelerating, but while that may be true of technology, it isn’t true of politics and culture.

- TED talks have too much faith in technology. Another futurism is possible.

- Capitalism is presented as being about rocket ships and nanomedicine. It is actually about Walmart jobs, McMansions and government spying.

He ends by talking about design. He argues that it shouldn’t be about innovation, but about innoculation. Design is presented in TED as the heroic solving a puzzles that will magically fix everything. Instead he argues for design as slogging through the hard stuff – understanding the politics and cultural issues.

He ends by summarizing why he feels TED is not just a distraction, but harmful. He believes TED misdirects our attention by charming us with the entertaining simple solutions while avoiding the messy, chaotic, complex issues that can’t be solved by technology.

I sometimes wonder if Humanities Computing didn’t serve a similar purpose in the humanities. Is it a form of comic (technological) relief from the brutal truths we confront in the humanities … especially the suspicion that we make no difference when we do confront racism, sexism, surveillance, politics and technohype. Why not relax and play a bit with the other?

WPA: Uses and Limitations of Automated Writing Evaluation

The Council of Writing Program Administrators has made available a very useful Research Bibliography on the Uses and Limitations of Automated Writing Evaluation Software (PDF). This is part of a set of WPA-ComPile Research Bibliographies. There are paragraph long summaries of the articles that are quite useful.

What seems to be missing is an ethical discussion of automated evaluation. Do we need to tell people if we use automated evaluation? Writing for someone feels like a very personal act (even in a large class). What are the expectations of writers that their writing would be read?

Kindred Britain

Susan alerted me to an interesting interactive of Kindred Britain that lets you see how different luminaries in British history are connected. This interactive is difficult to use at first. You should really go though the tutorial that opens immediately as the visualizations and controls are not obvious. Once you do you are rewarded with a three layered visualization:

- Network

- Timeline, and

- Geography

These layers are linked so manipulating one changes things in the others. The authors have written essays on what they did.

Grad Student Mini-Conference On The Digital Humanities

Stéfan Sinclair invited me to a half-day conference and lunchy that closed his LLCU-602: Digital Humanities – New Approaches to Scholarship course. You can see my conference notes at Grad Student Mini-Conference On The Digital Humanities. At lunch while the others were eating I was asked to talk about careers in the digital humanities. My talk was on “Thinking Through” as a practice in the humanities that is open to the digital. I started by talking about the recent Von Trotta film about Hannah Arendt which presents Arendt as an uncompromising advocate for thinking for oneself. I tried to spin out how one might think for oneself through the epochal interactive matter we have before us.

What I didn’t have time to argue was how thinking through is for me an alternative way of characterizing what we do in the digital humanities. It is an alternative, on the one hand, to Willard McCarty’s argument for modeling (as the model, so to speak), and Matt Kirchenbaum’s argument that for the digital humanities “as/is” tactical.

My argument suffers from some of the same problems that Fish finds in Ramsay’s work (in whose company I quite happy to be); namely that I find the digital humanities both to be an extension of existing humanistic ways of thinking and also a new way. I tried to show how it is simultaneously an old way of thinking and a new one. What has changed is the matter(s) we think through and the dangers we ford. The new matters are the digital evidence and computing affordances. The new dangers are the discourses of efficiency and instrumentality.

An Alberta researcher offers object lessons in the gamification of learning

I was interviewed by email the other day by Danny Bradbury from the Commerce Lab. The interview is now up at An Alberta researcher offers object lessons in the gamification of learning. Rereading the interview I’m struck by the disconnect between the research we do and what industry does. We do research for the sake of research, but often we don’t connect the research to the concrete problems of practicioners whether a teacher or in industry. For that matter, in the academy, most of us really don’t know much about the realities in business any more than other consumers. We make assumptions, but don’t check them. We don’t actually know what sort of research has been done or not in industry. That isn’t all our fault as industry tends to guard its research as a competitive advantage. Jane Jacobs in Systems of Survival describes the deep differences as between two ethical systems:

- The Guardian system which is open and sharing, uses force and shuns trade.

- The Commercial system that is competitive, thrifty, innovative and industrious

Continue reading An Alberta researcher offers object lessons in the gamification of learning

Defining Digital Humanities

Melissa Terras, Julianne Nyhan and Edward Vanhoutte have just edited a reader on Defining Digital Humanities. I have two works in this collection, “Is Humanities Computing an Academic Discipline”, which is a paper I gave for a seminar at the University of Virginia, and a blog entry “Inclusion in the Digital Humanities”. I also note that they have selected definitions (of DH) from the Day of Digital Humanities. This seems to be a trend now – books introducing the field include definitions culled from the project.

Interpreting the CSEC Presentation: Watch Out Olympians in the House!

The Globe and Mail has put up a high quality version of the CSEC (Communications Security Establishment Canada) Presentation that showed how they were spying on the Brazilian Ministry of Mines and Energy. The images are of slides for a talk on “CSEC – Advanced Network Tradecraft” that was titled, “And They Said To The Titans: «Watch Out Olympians In The House!»”. In a different, more critical spirit of “watching out”, here is an initial reading of the slides. What can we learn about how organizations like CSEC are spying on us? What can we learn about how they think about their “tradecraft”? What can we learn about the tools they have developed? What follows is a rhetorical interpretation.