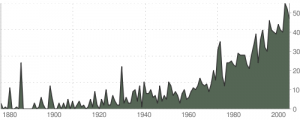

Back to Pontypool, the semiotic zombie movie that has infected me. The image above is of the poster for the missing cat Honey that seems to have something to do with the start of the semiotic infection. The movie starts with Grant Mazzy’s voice over the radio talking about,

Mrs French’s cat is missing. The signs are posted all over town. Have you seen Honey? Well, we have all seen the posters, but nobody has seen Honey the cat. Nobody, until last Thursday morning when Miss Collettepiscine … (drove off the bridge to avoid the cat)

He goes on to pun on “Pontypool” (the name of the town the movie takes place in), Miss Collettepiscine’s name (French for “panty-pool”), and the local name of the bridge she drove off. He keeps repeating variations of Pontypool a hint at the language virus to come.

As for the language virus, I replayed parts of the movie where they talk about it. At about 58 minutes in they hear the character Ken clearly get infected and begin to repeat himself as they talk on the cellphone. Dr. Mendez concludes, “That’s it, he is gone. He is just a crude radio signal, seeking.” A little later Mendez gets it and proposes,

Mendez: No … it can’t be, it can’t be. It’s viral, that much is clear. But not of the blood, not of the air, not on or even in our bodies. It is here.

Grant: Where?

Mendez: It is in words. Not all words, not all speaking, but in some. Some words are infected. And it spreads out when the contaminated word is spoken. Ohhhh. We are witnessing the emergence of a new arrangement for life … and our language is its host. It could have sprung spontaneously out of a perception. If it found its way into language it could leap into reality itself, changing everything. It may be boundless. It may be a God bug.

Grant: OK, Dr. Mendez. Look, I don’t even believe in UFOs, so I … I’ve got to stop you there with that God bug thing.

Mendez: Well that is very sensible because UFOs don’t exist. But I assure you, there is a monster loose and it is bouncing through our language, frantically trying to keep its host alive.

Grant: Is this transmission itself … um …

Mendez: No, no, no, no. If the bug enters us, it does not enter by making contact with our eardrum. It enters us when we hear the word and we understand it. Understand?

It is when the word is understood that the virus takes hold. And it copies itself in our understanding.

Grant: Should we be … talking about this?

Sydney: What are we talking about?

Grant: Should we be talking at all?

Mendez: Well, to be safe, no, probably not. Talking is risky, and well, talk radio is high risk. And so … we should stop.

Grant: But, we need to tell people about this. People need to know. We have to get this out.

Mendez: Well it’s your call Mr Mazzy. But let’s just hope that your getting out there doesn’t destroy your world.

As one thoughtful review essay points out, Pontypool is not the first to play with the meme of information viruses that can infect us. Snow Crash, the Stephenson novel which features a language-virus, even appears in the movie.

Pontypool itself is infectious, morphing from form to form. Sequels are threatened. The book, Pontypool Changes Everything, which starts with a character who keeps Ovid’s Metamorphoses in his, led to the movie which led to the radio play which was created by re-editing the movie audio (and it apparently has a different ending with “paper”.)