Calen H. sent me a link to a very funny YouTube video on Opera Face Gestures. The idea is to control the Opera browser by making faces. Almost good enough to be implemented.

H. P. Luhn, KWIC and the Concordance

We all know that the Google display comes indirectly from the Concordance, but I have found in Luhn’s 1966 “Keyword-in-Context Index for Technical Literature (Kwic Index)” the explicit recognition of the link and the reason for drawing on the concordance.

the significance of such single keywords could, in most instances, be determined only by referring to the statement from which the keyword had been chosen. This somewhat tedious procedure may be alleviated to a significant degree by listing selected keywords together with surrounding words that act as modifiers pointing up the more specific sense in which a keyword has been applied. This method of indexing words is well established in the process of compiling concordances of important works of literature of the past. The added degree of information conveyed by such keyword-in-context indexes, or “KWIC Indexes” for short, can readily be provided by automatic processing. (p. 161)

The problem for Luhn is that simply retrieving words doesn’t give you a sense of their use. His solution, first shown in the late 1950s, was to provide some context (hence “keyword-in-context”) so that readers can disambiguate themselves and make decisions about which index items to follow. It is from the KWIC that we ultimately get the concordance features of the Google display, though it should be noted that Luhn was proposing KWIC as a way of printing automatically generated literature indexes where the kewwords were in the titles. In this quote Luhn explicitly acknowledges that this is a method well established in concordances.

There is also a link between Luhn and Father Busa. According to Black, quoted in Marguerite Fischer, “The Kwic Index Concept: A Retrospective View”,

the Pontifical Faculty of Philosophy in Milan decided that they would make an analytical index and concordance to the Summa Theologica of St. Thomas Aquinas, and approached IBM about the possibility of having the operations performed on Data Processing. Experience gained in this project contributed towards the development of the KWIC Index. (This is a quote on page 123 from Black, J. D., 1962, “The Keyword: Its Use in Abstracting, Indexing, and Retrieving Information”.)

From the concordance to KWIC through to Google?

For some historical notes on Luhn see, H. P. Luhn and Automatic Indexing.

Drucker: Blind Spots

Johanna Drucker has an essay in the Chronicle about how humanists should be involved developing their work environments, Blind Spots. She has a nice phrase for the attitude by some scholars that someone else should do the work of developing the knowledge environment of the future – she calls it the “hand-waving magic wand approach to the future”. She concludes here essay,

Unless scholars in the humanities help design and model the environments in which they will work, they will not be able to use them. Tools developed for PlayStation and PowerPoint, Word, and Excel will be as appropriate to our intellectual labors as a Playskool workbench is to the chores of a real plumber. I once bought a very beautiful portable Olivetti typewriter because an artist friend of mine said it was so elegantly designed that it had been immediately put into the Museum of Modern Art collection. The problem? It wasn’t designed for typing. Any keyboardist with any skill at all constantly clogged its keys. A thing of beauty, it was a pain forever. I finally threw it from the fourth-floor tower of Wurster Hall at the University of California at Berkeley. Try doing that with the interface to your university library. Now reflect on who is responsible for getting it to work as an environment that supports scholarship.

We face a critical juncture. Leaving it to “them” is unfair, wrongheaded, and irresponsible. Them is us.

Johanna’s essay is addressed to scholars reminding us that we need to take responsibility for working things out. There is, however, another audience that needs to be addressed and that is the audience that believes that humanists aren’t the right people to be involved in designing infrastructure. The argument would be that there are professional software engineers who are trained to design portals for communities – they should be given the job so we don’t end up reinventing the wheel or doing a poor job. Obviously the answer lies in a creative design collaboration and humanists with computing development experience can play a crucial role in the mix, but how do we build such teams?

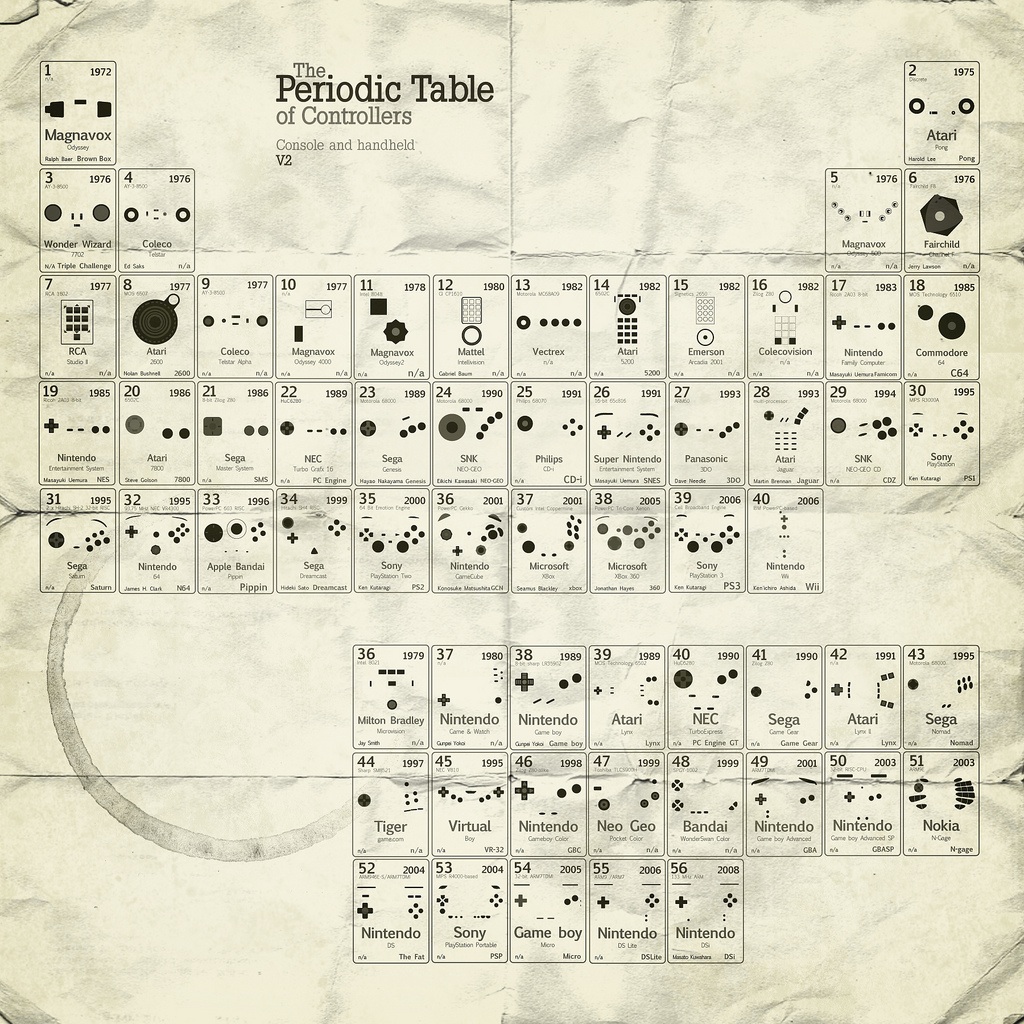

periodic table of controllers V.2

Derek P. pointed my class on Computers and Culture to this periodic table of controllers on Flickr. This is version “V.2 UPDATED” and presents an history of video game (both consoles and handheld) controller buttons and knobs. It uses the periodic table as a design idea. Attractive and fascinating to look through. I almost see a pattern

Clay Shirky: Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable

Thanks to Peter O I came across Clay Shirky’s excellent analysis of what’s going on with newspapers and the web, Newspapers and Thinking the Unthinkable . Some of the salient points:

- Change has been so rapid that it has changed who is pragmatic and who is a fabulist. Newspapers are in denial about the realities of online content so those who describe what is happening (the pragmatists) are treated as fabulists.

Revolutions create a curious inversion of perception. In ordinary times, people who do no more than describe the world around them are seen as pragmatists, while those who imagine fabulous alternative futures are viewed as radicals. The last couple of decades haven’t been ordinary, however. Inside the papers, the pragmatists were the ones simply looking out the window and noticing that the real world was increasingly resembling the unthinkable scenario. These people were treated as if they were barking mad. Meanwhile the people spinning visions of popular walled gardens and enthusiastic micropayment adoption, visions unsupported by reality, were regarded not as charlatans but saviors.

When reality is labeled unthinkable, it creates a kind of sickness in an industry.

- The economics of publishing have changed. It used to be that there was a tremendous upfront cost to set up a newspaper or broadcasting facility. Now the infrastructure of distribution is paid for by all so publishing is cheap.

With the old economics destroyed, organizational forms perfected for industrial production have to be replaced with structures optimized for digital data. It makes increasingly less sense even to talk about a publishing industry, because the core problem publishing solves — the incredible difficulty, complexity, and expense of making something available to the public — has stopped being a problem.

- It is easy to describe life before or after an epochal shift. It is hard to describe the chaos of experiments during the shift. Shirky looks to The Printing Press as an Agent of Change as an example of the hard type of history.

What Eisenstein focused on, though, was how many historians ignored the transition from one era to the other. To describe the world before or after the spread of print was child’s play; those dates were safely distanced from upheaval. But what was happening in 1500? The hard question Eisenstein’s book asks is “How did we get from the world before the printing press to the world after it? What was the revolution itself like?â€

- Advertisers don’t want to pay for the costs of a full-featured newspaper (with international bureaus and investigative reporting.) They will move their money to where it connects with their (usually local) audience.

The competition-deflecting effects of printing cost got destroyed by the internet, where everyone pays for the infrastructure, and then everyone gets to use it. And when Wal-Mart, and the local Maytag dealer, and the law firm hiring a secretary, and that kid down the block selling his bike, were all able to use that infrastructure to get out of their old relationship with the publisher, they did. They’d never really signed up to fund the Baghdad bureau anyway.

- Newspaper reporting provides a public service that will be missed, but knowing we will miss it doesn’t save it. We just don’t know how to fill the gap that will be left when daily papers dissappear in cities.

“You’re gonna miss us when we’re gone!†has never been much of a business model. So who covers all that news if some significant fraction of the currently employed newspaper people lose their jobs?

I don’t know. Nobody knows. We’re collectively living through 1500, when it’s easier to see what’s broken than what will replace it.

Actually I think there are ideas floating around as to what might fill the gap:

- Blogs may take up some of the slack with various advocacy groups and NGOs providing investigative reporting in the areas that concern them. I think it is wrong to assume that amateurs will necessarily do a worse job than professional reporters. In fact, as most know, professionals are too busy to usually go into depth and whenever they write about something you know they get it wrong in all sorts of ways. A blog like Buckets of Grewal probably does a more indepth job of examining the Grewal controversy than any newspaper story. The difference is rather that the professionals are committed to breadth and they write better.

- Publicly funded broadcasters like the BBC and the CBC will provide tax funded news reporting with foreign bureaus and so on. They don’t have to have make a profit and can invest in things perceived as useful for society.

- There will always be some big and international newspapers like the New York Times or Reuters because there will always be a demand for that sort of news. The internet reduces diversity – every city doesn’t need a newspaper with a foreign bureau. All we need is a couple of news services with foreign bureaus.

- Some companies have already figured out how to package news as analysis and get other businesses to pay for it. This will accelerate as newspapers fail. Companies like Oxford Analytica will meet the demand of multinational businesses who need access to strategic information. The sooner the newspapers fail the sooner we will see these companies come out of the woodwork and start selling their products to us.

To conclude with another quote from the Shirky essay, “Society doesn’t need newspapers. What we need is journalism.”

Google Notebook Stopped

According to the Official Google Notebook Blog they are stopping development on the Google Notebook. I rather liked Google Notebook for gathering notes, to do lists, and so on. Google Docs doesn’t have the same ease of use. Oh well, time to find something else.

THRU YOU | Kutiman mixes YouTube

From Peter O and others the amazing YouTube remix, THRU YOU | Kutiman mixes YouTube. Alarmingly good music.

And from Peter R a link to Extreme Sheet LED Herding. Flock remix.

INKE: Implementing New Knowledge Environments

Congratulations to Ray Siemens and company for INKE: Implementing New Knowledge Environments which got funding as a Major Collaborative Research Initiative from SSHRC. I’m part of the Interface Design group led by Stan Ruecker.

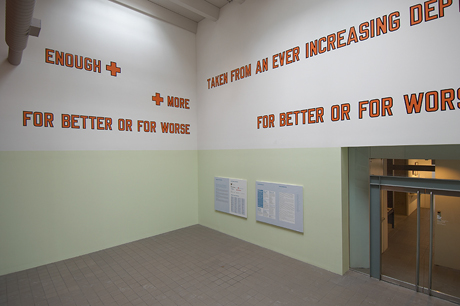

The Power Plant: Laurence Weiner

The Globe and Mail has a review of the Lawrence Weiner show at the The Power Plant in Toronto (who must have one of the worst gallery web sites I’ve seen in a long time – lots of navigation for no content in very small type!) e-flux has a better site about the show.

The Globe and Mail article, “Brilliantly maddening word sculptures” by Gary Michael Dault (Thursday, March 19th, 2009, Section R, p. 1) nicely explores the issues around language and art raised by such conceptual work. Dault walked through the show with Weiner and Dault ends the articles with,

We talk about whether language actually means anything at all. “Language does mean something,†Weiner contends gaily, “but not what you thought it meant.†There’s the other side of a cul-de-sac for you.

Weiner’s sculpture with words goes back to the 1960s. His Declaration of Intent (1968) articulates a relationship between instructions for a work of art and the fabricated work.

“1. The artist may construct the piece. 2. The piece may be fabricated. 3. The piece need not be built. Each being equal and consistent with the intent of the artist the decision as to condition rests with the receiver upon the occasion of receivership.”

Does it matter if the work is actually put together from bits and pieces? Do the bits and pieces of social media (like the bits of blog entires, or the pictures of words in the Dictionary) make a whole or its semblance?

MIT: Open Access Mandate

From Twitter I found a link to Peter Suber, Open Access News where there is a story of MIT’s unanimous faculty vote to adopt an Open Access mandate that gives the University the right to archive and make available their articles. Like the Harvard mandate, faculty can opt out if they have a good reason.

Each Faculty member grants to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology nonexclusive permission to make available his or her scholarly articles and to exercise the copyright in those articles for the purpose of open dissemination.