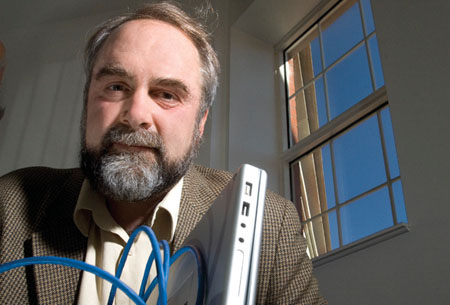

Richard drew my attention to the upcoming competition between IBM’s Watson deep question and answer system and top Jeopardy! champions, IBM’s “Watson” Computing System to Challenge All Time Greatest Jeopardy! Champions. I’d blogged on Watson before – it’s a custom system designed to mine large collections of data for answers to questions. Here is what IBM says its applications are,

Beyond Jeopardy!, the technology behind Watson can be adapted to solve problems and drive progress in various fields. The computer has the ability to sift through vast amounts of data and return precise answers, ranking its confidence in its answers. The technology could be applied in areas such as healthcare, to help accurately diagnose patients, to improve online self-service help desks, to provide tourists and citizens with specific information regarding cities, prompt customer support via phone, and much more.