I finally got around to reading the latest Pamphlets of the Stanford Literary Lab. This pamphlet, 12. Literature Measured (PDF) written by Franco Moretti, is a reflection on the Lab’s research practices and why they chose to publish pamphlets. It is apparently the introduction to a French edition of the pamphlets. The pamphlet makes some important points about their work and the digital humanities in general.

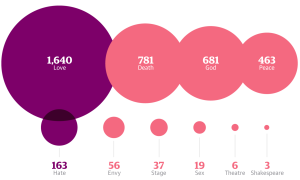

Images come first, in our pamphlets, because – by visualizing empirical findings – they constitute the specific object of study of computational criticism; they are our “text”; the counterpart to what a well-defined excerpt is to close reading. (p. 3)

I take this to mean that the image shows the empirical findings or the model drawn from the data. That model is studied through the visualization. The visualization is not an illustration or supplement.

By frustrating our expectations, failed experiments “estrange” our natural habits of thought, offering us a chance to transform them. (p. 4)

The pamphlet has a good section on failure and how that is not just a rhetorical ploy, but important to research. I would add that only certain types of failure are so. There are dumb failures too. He then moves on to the question of successes in the digital humanities and ends with an interesting reflection on how the digital humanities and Marxist criticism don’t seem to have much to do with each other.

But he (Bordieu) also stands for something less obvious, and rather perplexing: the near-absence from digital humanities, and from our own work as well, of that other sociological approach that is Marxist criticism (Raymond Williams, in “A Quantitative Literary History”, being the lone exception). This disjunction – perfectly mutual, as the indiference of Marxist criticism is only shaken by its occasional salvo against digital humanities as an accessory to the corporate attack on the university – is puzzling, considering the vast social horizon which digital archives could open to historical materialism, and the critical depth which the latter could inject into the “programming imagination”. It’s a strange state of a airs; and it’s not clear what, if anything, may eventually change it. For now, let’s just acknowledge that this is how things stand; and that – for the present writer – something needs to be done. It would be nice if, one day, big data could lead us back to big questions. (p. 7)