This evening we are hosting a video conferencing talk by Edward Snowden at the University of Alberta. These are some live notes taken during the talk for which I was one of the moderators. Like all live notes they will be full of misunderstandings.

Joseph Wiebe of Augustana College gave the introduction. Wiebe asked what is the place of cybersecurity in public life?

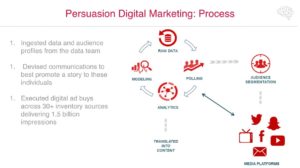

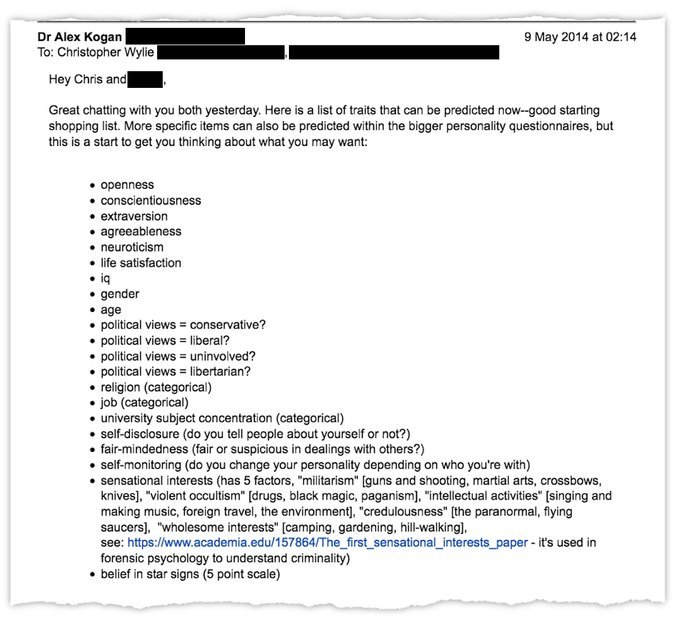

“What an incredible time?” is how Snowden started, talking about the Cambridge Analytica and Facebook story. Technology is changing and connecting across borders. We are in the midst of the greatest redistribution of power in the history of humankind without anyone being asked for their vote or opinion. Large platforms take advantage of our need for human connection and turn our desires into a weakness. They have perfected the most effective system of control.

The revelations of 2013 were never about just surveillance, they were about democracy. We feel something has been neglected in the news and in politics. It is the death of influence. It is a system of manipulation that robs us of power by a cadre of the unaccountable. It works because it is largely invisible and is all connected to the use and abuse of our data. We are talking about power that comes from information.

He told us to learn from the mistake of 5 years ago and not focus too much on surveillance, but to look beyond the lever to those putting their weight on it.

Back to the problem of illiberal technologies. Information and control is meant to be distributed among the people. Surveillance technology change has outstripped democratic institutions. Powerful institutions are trying to get as much control of these technologies as they can before their is a backlash. It will be very hard to take control back once everyone gets used to it.

Snowden talked about how Facebook was gathering all sorts of information from our phones. They (Facebook and Google) operate on our ignorance because there is no way we can keep up with changes in privacy policies. Governments are even worse with laws that allow mass surveillance.

There is an interesting interaction between governments with China modelling its surveillance laws on those of the US. Governments seem to experiment with clearly illegal technologies and the courts don’t do anything. Everything is secret so we can’t even know and make a decision.

What can we do when ordinary oversight breaks down and our checks and balances are bypassed. The public is left to rely on public resources like journalism and academia. We depend then public facts. Governments can manipulate those facts.

This is the tragedy of our times. We are being forced to rely on the press. This press is being captured and controlled and attacked. And how does the press know what is happening? They depend on whistleblowers who have no protection. Governments see the press as a threat. Journalists rank in the hierarchy of danger between hackers and terrorists.

What sort of world will we face when governments figure out how to manage the press? What will we not know without the press.

One can argue that extraordinary times call for extraordinary measures, but who gets to decide? We don’t seem to have a voice even through our elected officials.

National security is a euphemism. We are witnessing the construction of a world where the most common political value is fear. Everyone argues we are living in danger and using that to control us. What is really happening is that morality has been replaced with legalisms. Rights have become a vulnerability.

Snowden disagrees. If we all disagree then things can change. Even in the face of real danger, there are limits to what should be allowed. Following Thoreau we need to resist. We don’t need a respect for the law, but for the right. The law is no substitute for justice or conscience.

Snowden would not be surprised if Facebook’s final defense is that “its legal.” But we need to ask if it is right. A wrong should not be turned into a right. We should be skeptical of those in power and the powers that shape our future. There times in history and in our lives when the only possible decision is to break the law.