In 1944 the Journal of Educational Sociology had an issue on “The Comics as an Educational Media”. The Editorial by Harvey Zorbaugh began by quoting Sterling North of the Chicago Daily News who wrote,

Virtually every child in America is reading color “comic” magazines- a poisonous mushroom growth of the last two years. …

Badly drawn, badly written and badly printed – a strain on young eyes and young nervous systems – the effect of these pulp-paper nightmares is that of a violent stimulant. (p. 193-4)

Zorbaugh and the other authors of the articles collected in this issue are, however, interested in how comics can be leveraged for learning. Zorbaugh ends his editorial with,

It is time the amazing cultural phenomenon of the growth of the comics is subjected to dispassionate scrutiny. Somewhere between vituperation and complacency must be found a road to the under- standing and use of this great new medium of communication and social influence. For the comics are here to stay.

I was struck reading this journal issue how we are going through the same motons with videogames. We have public anxiety about video games, we worry that videogames are violent stimulants, and yet we recognize they are here to stay. Someone gets the bright idea then of trying to create serious games that stimulate the mind, not violence. Academics (like me) follow. Here is the argument from one of the other articles in the issue,

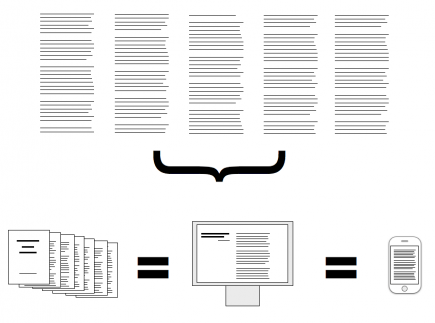

In recent decades, invention and technology have developed motion pictures, the radio, and, latterly, the comic. The first two have already been harnessed to the purposes of education. It is appropriate to examine from the standpoint of educational method this most recently ar- rived entertainment device that has attracted such an extraordinary following. Any form of language that reaches one hundred million1 of our people naturally engages the attention of educationists, whose major activity is communication. (W. W. D. Sones, “The Comics and Instructional Method”, p. 232.)

What then happened to serious comics? I can’t think of any educational comics even though I collected comic books as a kid. Were serious educational comics a failure? If they were, what does that suggest for serious games? It is tempting to say that the lesson of educational comics is that serious games too will vanish as another educational fad. I suspect there are other answers:

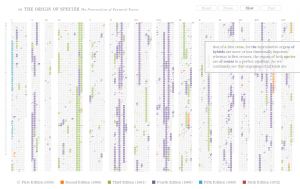

- Perhaps serious comics did work. There were, after all, educational comics like GE’s Adventures in Electricity. Perhaps they were effective educational (and promotional) tools even if never as popular with youth as action comics. Now, of course, we have a wealth of serious graphic novels like Maus by Art Spiegelman.

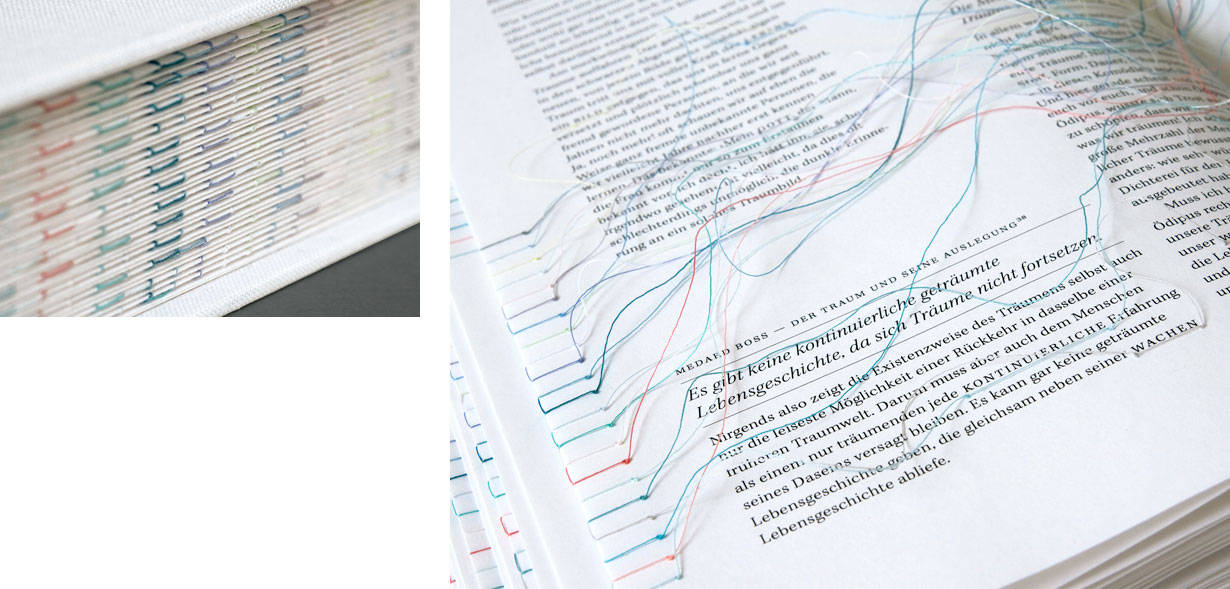

- Perhaps textbooks learned from comic artists and began to use graphic elements where they illustrated the point. Many of the books I read my children like those by David Macaulay (Castle, City, Cathedral, and The Way Things Work) were drawn, though they didn’t use all the comic conventions. The comic may have evolved as it got serious.

- Society eventually finds a way to manage new media. No one thinks comics are poisoning our children any more. Something happened and now comics are not the threat. Hence we don’t need to tame them any more … or perhaps they aren’t the threat because we tamed them?