Reading Andrew Booth’s Mechanical Resolution of Linguistic Problems (1958) I came across some interesting passages about the beginnings of text computing that suggest an alternative to the canonical Roberto Busa story of origin. Booth (the primary author) starts the book with a “Historical Introduction” in which he alludes to Busa’s project as part of a list of linguistic problems that run parallel to the problems of machine translation:

In parallel with these (machine translation) problems are various others, sometimes of a higher, sometimes of a lower degree of sophistry. There is, for example the problem of the analysis of the frequency of occurence of words in a given text. … Another problem of the same generic type is that of constructing concordances for given texts, that is, lists, usually in alphabetic order, of the words in these texts, each word being accompanied by a set of page and line references to the place of its occurrence. … The interest at Birkbeck College in this field was chiefly engendered by some earlier research work on the Dialogues of Plato … Parallel work in this field has been carried out by the I.B.M. Corporation, and it appears that some of this work is now being put to practical use in the preparation of a concordance for the works of Thomas Aquinas.

A more involved application of the same sort is to the stylistic analysis of a work by purely mechanical means. (p. 5-6)

In Mechanical Resolutions he continues with a discussion of how to use computers to count words and to generate concordances. He has a chapter on the problem of Plato’s dialogues which seems to have been a set problem at that time and, of course, there are chapters on dictionaries and machine translation. He describes some experiments he did starting in the late 40s that suggest that Searle’s Chinese Room Argument of 1980 might have been based on real human simulations.

Although no machine was available at this time (1948), the ideas of Booth and Richens were extensively tested by the construction of limited dictionaries of the type envisaged. These were used by a human untutored in the languages concerned, who applied only those rules which could eventually be performed by a machine. The results of these early ‘translations’ were extremely odd, … (p. 2)

Did others run such simulations of computing with “untutored” humans in the early years when they didn’t have access to real systems? See also the PDF of Richens and Booth, Some Methods of Mechanized Translation.

As for Andrew D. Booth, he ended up in Canada working on French/English translation for the Hansard, the bilingual transcript of parlimentary debates. (Note that Bill Winder has also been working on these, but using them as source texts for bilingual collocations. ) Andrew and Kathleen Booth wrote a contribution on The Origins of MT (PDF) that describes his early encounters with pioneers of computing around the possibilities of machine translation starting in 1946.

We date realistic possibilities starting with two meetings held in 1946. The first was between Warren Weaver, Director of the Natural Sciences Division of the Rockefeller Foundation, and Norbert Wiener. The second was between Weaver and A.D. Booth in that same year. The Weaver-Wiener discussion centered on the extensive code-breaking activities carried out during the World War II. The argument ran as follows: decryption is simply the conversion of one set of “words”–the code–into a second set, the message. The discussion between Weaver and A.D. Booth on June 20, 1946, in New York identified the fact that the code-breaking process in no way resembled language translation because it was known a priori that the decrypting process must result in a unique output. (p. 25)

Booth seems to have successfully raised funds from the Nuffield Foundation for a computer at Birkbeck College at the University of London that was used by L. Brandwood for work on Plato, among others. In 1962 he and his wife migrated to Saskatchewan to work on bilingual translation and then to Lakehead in Ontario where they “continued with emphasis on the construction of a large dictionary and the use of statistical techniques in linguistic analysis” in 1972. They retired to British Columbia in 1978 as most sensible Canadians do.

In short, Andrew Booth seems to have been involved in the design of early computers in order to get systems that could do machine translation and that led him to support a variety of text processing projects including stylistic analysis and concording. His work has been picked up as important to the history of machine translation, but not for the history of humanities computing. Why is that?

In a 1960 paper on The future of automatic digital computers he concludes,

My feeling on all questions of input-output is, however, the less the better. The ideal use of a machine is not to produce masses of paper with which to encourage Parkinsonian administrators and to stifle human inventiveness, but to make all decisions on the basis of its own internal operations. Thus computers of the future will communicate directly with each other and human beings will only be called on to make those judgements in which aesthetic considerations are involved. (p. 360)

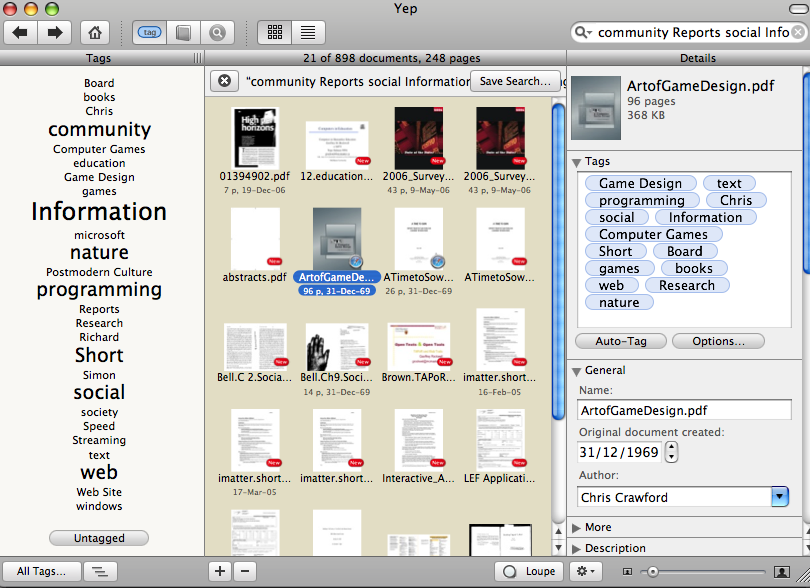

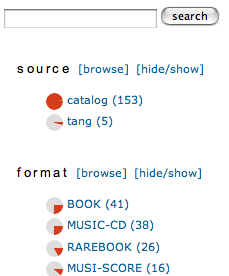

Blacklight is a neat project that Bethany Nowviskie pointed me to at the University of Virginia. They have indexed some 3.7 million records from their library online catalogue and set up a faceted search and browse tool.

Blacklight is a neat project that Bethany Nowviskie pointed me to at the University of Virginia. They have indexed some 3.7 million records from their library online catalogue and set up a faceted search and browse tool.