Domenico pointed me to an entry on InfoLet (a blog he and others keep in Italian on informatics and literature.) The entry announces a book La macchina nel tempo: Studi di informatica umanistica in onore did Tito Orlandi that brings together many of the top digital humanists in Italy to celebrate Tito Orlandi’s contribution to the field. You can order online at http://www.lelettere.it. Continue reading The machine in time: In honour of Tito Orlandi

Category: Internet Culture and Technology

Staff to be banned from sending emails

“The deluge of information will be one of the most important problems a company will have to face (in the future). It is time to think differently.” Reading useless messages is terrible for concentration, as it takes 64 seconds to get back on the ball after doing so, according to a recent study by the social and business responsibility watchdog ORSE. “Poorly controlled, the email can become a devastating tool,” it warned.

There is more and more criticism of email and how it can distract you. Here is an article from the Telegraph about a French company where Staff to be banned from sending emails. What is interesting is that the CEO of Atos is advocating using instant messaging and a Facebook-like social network. This is supposed to be less distracting.

Akihabara: Otaku Holy Land

If you are interested in Japanese otaku culture you have probably heard about Akhihabara or Akiba for short. Akiba is a neighbourhood of Tokyo famous for electronics shops, game shops, maid cafés and arcades. I was lucky to get a tour of Akiba by Michiya Kawajiri and Kiyonori Nagasaki on November 30th, 2011. Akiba is similar to Osaka’s Nipponbashi neighbourhood, but larger and with maid cafés. You can see my photos of Akihabara on Flickr.

Web literature in China

From a story in the Guardian I discovered that online reading is taking off in China. According to China Daily story, Web literature turns a page with profitable storyline a large percentage of Chinese web users are reading long serialized novels for a 30-50 cents per 100,000 words (which is about a dollar for every 600-1000 pages!) The Guardian story Has China found the future of publishing? suggests that the convenience, the price, the type of serialized literature, the economic model (of independent authors and commercial sites), and the proliferation of e-readers has made it a viable business. I’m guessing that serialization is a way of discouraging pirates – people who want the next chapter will pay to get it as soon as possible.

Canadian Writing Research Collaboratory Launch

I am at the Canadian Writing Research Collaboratory (CWRC) launch. CWRC is building a collaborative editing environment that will allow editorial projects to manage the editing of electronic scholarly editions. Among other things CWRC is developing an online XML editor, a editorial workflow management tools, and integrated repository.

The keynote speakers for the event include Shawna Lemay and Aritha Van Herk.

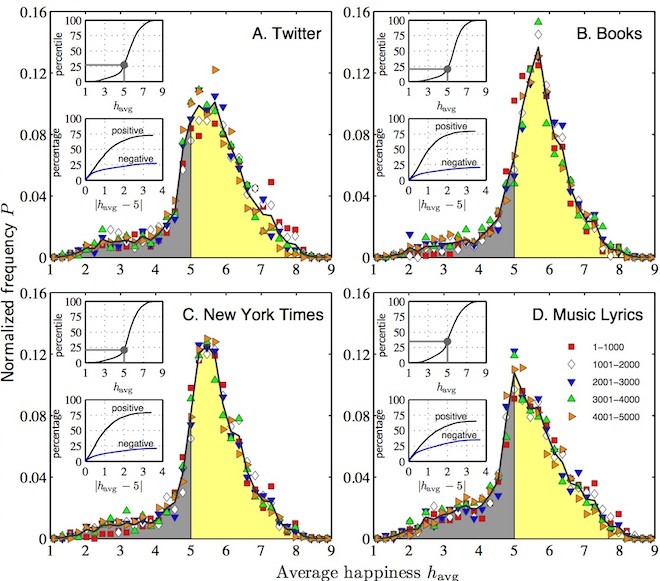

Happy Words Trump Negativity in the English Language

Happy Words Trump Negativity in the English Language is an interesting story about a study by Kloumann and colleagues on Positivity of the English Language. They used Mechanical Turk to get people to assess whether the high frequency words used in Twitter, Books, the New York Times and Music Lyrics were positive. Their study showed that overwhelmingly English is a positive language. Thanks to Stan for this.

Day of Archaeology

Megan pointed me to the ADay of Archaeology project. This project was conceived of during one of our Day of Digital Humanities projects and builds on the idea. It serves partly as community outreach for archaeology:

The Day of Archaeology 2011 aims to give a window into the daily lives of archaeologists. Written by over 400 contributors, it chronicles what they did on one day, July 29th 2011, from those in the field through to specialists working in laboratories and behind computers. This date coincides with the Festival of British Archaeology, which runs from 16th – 31st July 2011.

I also note that they had far more participants in their first year than we had even in our third! We need to learn from them.

Internet use and transactive memory – Contemplative Computing

From Humanist I was led to a good summary blog entry on Internet use and transactive memory. Transactive memory is a group or stored memory that we depend on instead of remember the information itself. We do this all the time (even before computers) when, for example, we depend on a cookbook for a recipe we have used before, but can’t be bothered to memorize. Given books like Carr’s The Shallows, there is debate about whether Google and the internet as transactive memory is making us stupider.

The real question is not whether offloading memory to other people or to things makes us stupid; humans do that all the time, and it shouldn’t be surprising that we do it with computers. The issues, I think, are 1) whether we do this consciously, as a matter of choice rather than as an accident; and 2) what we seek to gain by doing so.

This entry was sparked by recent news of research results on this subject by Dr. Sparrow and others (see YouTube interview). You can see Carr’s blog entry at Rough Type: Nicholas Carr’s Blog: Minds like sieves. Carr seems to think this reinforces his view that we are shifting to depending too much on technological transactive memory. Sparrow is more careful about drawing conclusions. We may have always depended on transactive memory, but are focusing now on one type – the internet. In Plato’s Phaedrus Socrates focused on writing as the technology tempting us to forget.

Of course, forgetting costs so we may not have to worry if we don’t want to pay.

The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood | James Gleick

I just finished Jame Gleick’s The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood. One of the best books I’ve read in some time. Despite its length (527 pages including index, bibliography and notes) it doesn’t exhaust the subject pedantically. Many of the chapters hint and more things to think about. It also takes an unexpected trajectory. I expected it to go from Babbage and the telegraph to computers and then Engelbart and information extensions. Instead he works his way through physics and math. He looks at ideas about how to measure information and the materiality of information explaining the startling conclusion that “Forgetting takes work.” (p. 362)

The second to last chapter “News News Every Day” is as good an exploration of the issue of information overload as I have read. He suggests that the perception of “overload” comes from the metaphoric application of our understanding of electrical circuits as in “overloading the circuits.” If one believes the nervous system is like an electrical network then it is possible to overload the network with too much input. That, after all, is what Carr argues in The Shallows (though he uses cognitive science.) None-the-less electrical and now computing metaphors for the mind and nervous system are haunting the discussion about information. Is one overloaded with information when you turn a corner in the woods and see a new vista of lakes and mountains? What Gleick does is connect information overload with the insight that it is forgetting that is expensive. We feel overloaded because it takes work not to find information, but to filter out information. To have peaceful moment thinking you need to forget and that is expensive.

Gleick ends, as he should, with meaning. Information theory ignores meaning, but information is not informative unless it means something to someone at some time. Where does the meaning come from? Is it interconnectedness? Does the hypertext network (and tools that measure connectedness like Google) give meaning to the data? No, for Gleick it is human choice.

As ever, it is the choice that informs us (in the original sense of that word). Selecting the genuine takes work; then forgetting takes even more work. (p. 425)

More on the Shallows

In an earlier blog post I mentioned distraction and Nicholas Carr’s book, The Shallows. Here is a more complete reaction now that I’ve finished the book.

Carr argues that the web is an interruption technology that is changing the way we think. The multiple media, the hypertext links, and the constant flow of information distract us. He surveys research on reading and how the brain handles multimedia. He argues that the web is changing our brains. Sustained “deep” reading is what we aren’t doing.

His argument looks for a balance of rapid surfing (flitting) and slow contemplation, reading, and thinking. His argument is partly cognitive – around the way our memory formation works. He argues that our memory is organic and not at all like a computer. To form the long term memories that shape our mind we need to go slow, to reinforce and to think about things. The hyperdistraction of the web overloads short term memory and inhibits the development of long term memories. These long term memories are not information stored (that is the computer analogy) but our mind. The long term shaping shapes processing not just storage. A good example (which he doesn’t use) is language. As you learn a language you learn to think in that language, not just to store vocabulary and grammatical rules.

Carr also attacks the technoliterati, especially Page and Brin of Google. He attacks them for arguing that the web (and Google) are offloading memory to free up space in our brains. This, he argues, is just wrong from a cognitive perspective. We don’t have a limit to storage because memory is not storage. To offload it is not to think it and not to let it shape you.

I’m not sure he is right that books are that much better, though he quotes some studies (about how hypertext, the foundation of the web, doesn’t help much.) It is probably quiet reading that is more conducive to thinking than books. I also wonder if some computer games are an example of sustained thinking toys.

There is in the last chapter “A Think Like Me” an interesting philosophical discussion about how we shape and are shaped by technologies. He quotes McLuhan to the effect that extensions numb us. If you extend your arm with a tool, then you don’t feel with your hands. If you extend your mind with a tool like the web then you numb your mind.

At times Carr is realistic that we want a balance. We like to be numbed from some things like the cold. We use houses even if they isolate us. The trick is probably to be able to choose the level of engagement and to choose how you want to think. I don’t want to think about the outside weather so I have a thermostat and automatic heating. I do want to think about other things.