The Game of Writing (Gwrit) project that I am part of just got support through a University of Alberta Blended Learning Award. See the 2014 Selected Courses. This award is going towards creating a flipped version of Writing 101, a service course that is being scaled up to support large sections by Roger Graves and Heather Graves. With the Blended Learning Award support from the Centre for Teaching and Learning and with Faculty of Arts funding we are redeveloping GWrit to be used in large sections of Writing 101. Here is part of the abstract of the proposal,

Research suggests that by creating a rich online environment for students to connect and interact with instructors and peers they can improve as writers. We are currently building a gamified online writing environment, The Game of Writing (GWrit), for Writing Studies 101 (WRS 101) that can support student writers and alumni. WRS 101 is a high demand service course required for many degree programs across the University. We are creating a large class version that blends face-to-face with gamification strategies. In GWrit students will choose and work on assignments or quests that are part of the course. Their progress on these assignments or quests will be shared with peers and instructional staff; in this way all students can see who is working on the same quests, and they can ask for help or advice from them. Informal assessment will be available online from peers in the class; from paid peer tutors; from GTAs; and from alumni. This represents a significant expansion of the informal assessment available in traditional face-to-face courses, where peers and sometimes the instructor give informal feedback. We also intend to invite alumni to post assignments/quests that come from a workplace writing context. Students who complete WRS 101 will continue to have access to GWrit throughout their undergraduate careers and as alumni.

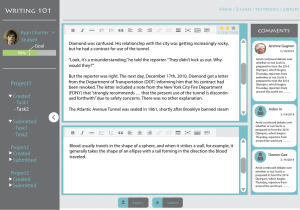

GWrit started as a prototype developed with support from GRAND. The original idea was an open writing environment where folks could challenge each other to compete at writing and where you could get analytics on your writing (number of words written, tasks completed, and visualizations like word clouds.) This research prototype is now being completely redeveloped by the Arts Resource Centre as a learning tool that can be used by students of our courses. We are adding commenting features so that students (and later alumni) can provide writing guidance in a structured fashion.