Thanks to James K I discovered Twitterfall which shows a waterfall of tweets based on keywords and other settings. An interesting example of what St̩fan Sinclair and I call a Knowledge Radio Рan application that organizes knowledge into a live stream.

Hacking as a Way of Knowing: Our Project on Flickr

I put a photo set up on Flickr for our Hacking as a Way of Knowing project. The set documents the evolution of the project which I’ve tentatively named the “ReReader for the Writing on the Wall”. Thanks to all those who made the project and the workshop a success. Now I have to think a bit deeper about making as knowing and things as theories.

Hacking as a Way of Knowing – Part 2

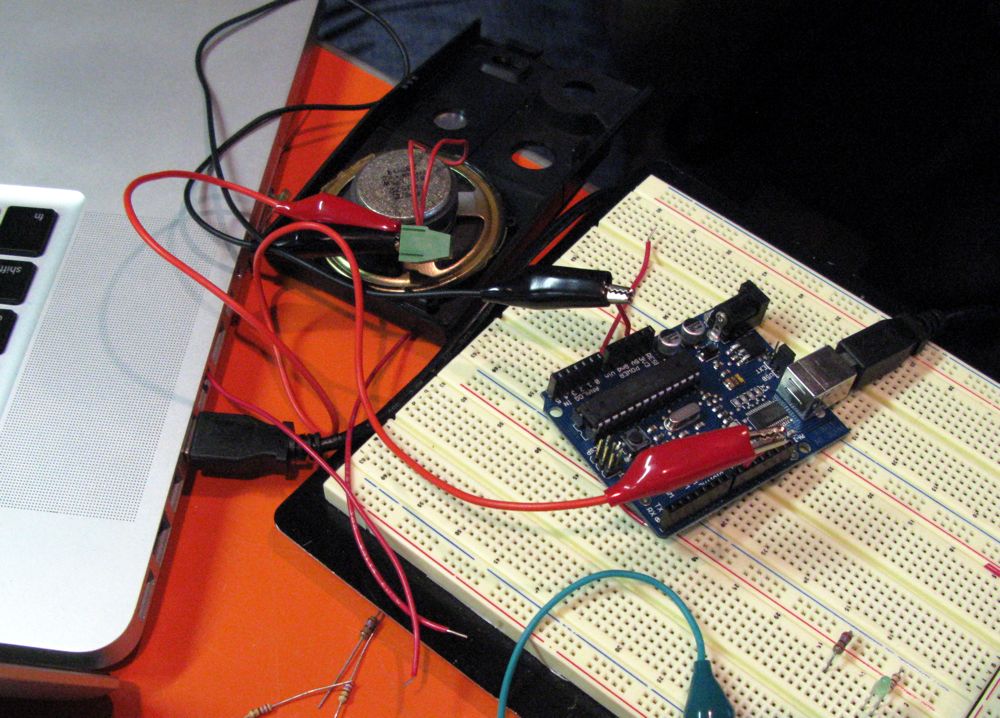

So a bunch of us started a project yesterday as part of the Hacking as a Way of Knowing workshop. Ours is, of course, the best project. We have motors that drive a reading of a fax carbon based on a “knowledge radio” on the Day of Digital Humanities.

Hacking as a Way of Knowing – Digital History

Today was the first day of the Hacking as a Way of Knowing e-waste fabrication workshop. Above you can see the text from a fax thermal printer roll projected onto a wall. (At least I think that’s what it is.) Below is an Arduino connected to a a speaker. Stéfan has working on taking a RSS feed and triggering events so we can connect stuff to it to create cool stuff.

We got talking about why fabrication is taking off. Turkel has his lab. Matt Ratto at the Univerity of Toronto has a lab (with a great name – CriticalMaking.com. Some of the reasons are:

- There is a growing amount of electronic waste visible and available to be repurposed (and reminding us of how much we waste.)

- As manufacturing moves out of North America we respond by exploring micro and personal manufacturing through fabrication. It is possible that this is the future of manufacturing here.

- As manufacturing becomes so complex that we can’t imagine how everyday things are made, fabrication gives us a way of thinking about the making of what’s around us. It allows us to reappropriate the everyday.

- The costs of fabrication (tools and materials) have dropped to the point where it is a viable hobby. What will fabrication look like when it is not longer only for those with skills?

- We have what I call an “Ikea” effect where the labour and costs for certain items is shifting. Ikea moved part of assembly (the end assembly that takes relatively little skill) to the buyer by creating smarter hardware. They shifted engineering smarts to joining technology that could be used by anyone. Fabrication benefits from a shift in smarts so that assembly can doable.

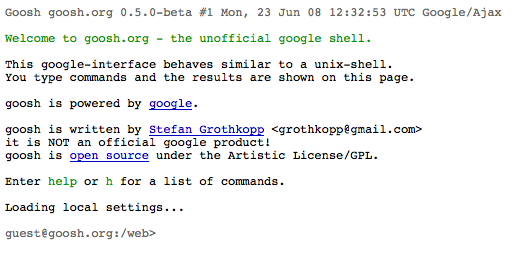

goosh.org – the unofficial google shell.

From Steve Ramsay’s twitter I discovered goosh.org – the unofficial google shell. What an idea! I’m not sure what I would use it for, but it seems dangerously close to brilliant.

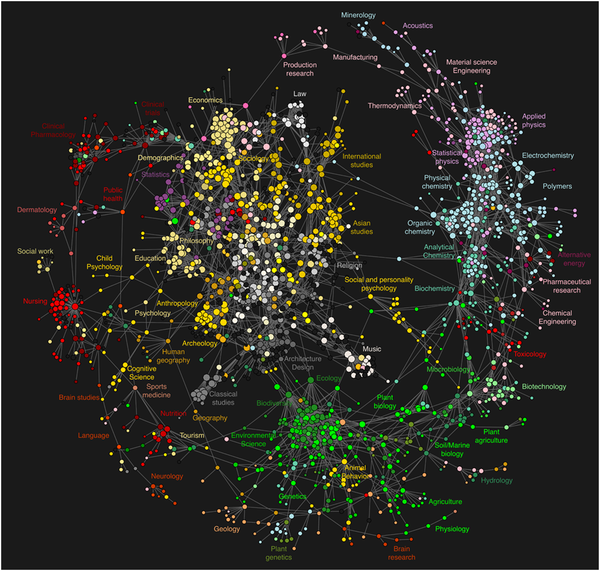

Clickstream Data Yields High-Resolution Maps of Science

Clickstream Data Yields High-Resolution Maps of Science is an article that presents an interesting view of the interdisciplinary relationships between the humanities and social sciences, on the one hand, and the sciences on the other. The article used “clickstream” data or usage data collected at various scholarly portals that show not citation links but connections in the activities of the users.

Clickstream Data Yields High-Resolution Maps of Science is an article that presents an interesting view of the interdisciplinary relationships between the humanities and social sciences, on the one hand, and the sciences on the other. The article used “clickstream” data or usage data collected at various scholarly portals that show not citation links but connections in the activities of the users.

The resulting model was visualized as a journal network that outlines the relationships between various scientific domains and clarifies the connection of the social sciences and humanities to the natural sciences.

They describe the visual appearance of the visualization (above) thus,

To provide a visual frame of reference, we summarize the overall visual appearance of the map of science in Fig. 5 in terms of a wheel metaphor. The wheel’s hub consists of a large inner cluster of tightly

connected social sciences and humanities journals (white, yellow and gray). Domain classifications for the journals in this cluster include international studies, Asian studies, religion, music, architecture and design, classical studies, archeology, psychology, anthropology, education, philosophy, statistics, sociology, economics, and finance. The wheel’s outer rim results from a myriad of connections in M’ between journals in the natural sciences (red, green, blue). In clockwise order, starting at 1PM, the rim contains physics, chemistry, biology, brain research, health care and clinical trials journals. Finally, the wheel’s spokes are given by connections in M’ that point from journals in the central hub to the outer rim.

This article came out of work funded by Mellon at the MESUR project.

Hacking as a Way of Knowing – Digital History

At the end of the week I’ll be going to Toronto for what I expect will be one of the most interesting workshops ever. William J. Turkel at Western has organized a hands-on workshop on Hacking as a Way of Knowing to reflect on electronic waste and data about the environment. The short description of the purpose is,

This three-day workshop will explore the theme of E-waste and environmental data. Working in small groups, participants will be given the task of hacking some typical consumer e-waste to create reflective technological assemblages that incorporate ‘nature’ in some form while calling one or more of our basic assumptions into question.

This is not so much about building something, but about thinking about how fabrication (hacking) is a way of thinking through AND in this case we will be thinking through the environment and all the waste around computing. I suspect I’m going to be embarassed by how much I waste.

IBM Watson: Question Answering for Jeopardy

From IBM Labs YouTube presence news of a IBM “Watson” System to Challenge Humans at Jeopardy! IBM’s Watson is a Question Answering system that IBM scientists hope “will be able to understand complex questions and answer with enough precision and speed to compete on Jeopardy!” (From the IBM press release.)

From IBM Labs YouTube presence news of a IBM “Watson” System to Challenge Humans at Jeopardy! IBM’s Watson is a Question Answering system that IBM scientists hope “will be able to understand complex questions and answer with enough precision and speed to compete on Jeopardy!” (From the IBM press release.)

Watson will be designed to deftly handle semantics “the meanings behind words” which will enable it to answer questions that require the identification of relevant and irrelevant content, the interpretation of ambiguous expression and puns, the decomposition of questions into sub-questions, and the logical synthesis of final answers. In addition, Watson will compute a statistical confidence in the responses it provides. Watson will be designed to do all of this in a matter of seconds, which will enable it to compete against humans, who have the ability to know what they know in less than a second. (From Addendum: About IBM’s Watson System)

The language IBM uses around this project is that of a “Grand Challenge.” It is smart how they have taken a analytical problem and used Jeopardy to give a target for the research, both in terms of speed and the types of questioning handled. Jeopardy also gives them a dramatic venue to demonstrate their progress just as Deep Blue playing Kasparov did.

The research is based on a Open Architecture for Question Answering (OAQA) that was jointly developed with Carnegie Mellon.

Present, Paper And Party

Yesterday I helped organize a gathering where graduate students here (and one prof) got to Present Papers And Party. The idea was that people presenting papers this summer could present informally and get some feedback. We had some interesting papers on games, but I could have structured the time better.

New Realities in Higher Education

New Realities in Higher Education is a blog gathering news about how the recession is affecting teaching in higher education.

The current and developing global recession is changing realities for students, institutions, and faculty members engaged in higher education. This blog chronicles those changes for academic / historical record purposes. Click on the header of each posting for the link to the complete news report.

I learned about this from the comments to a Tomorrow’s Professor entry about cutbacks at Stanford. The comments have been anonymized and are heartbreaking. A rough sense of what is happening and the attitudes:

- Many departments are having to cut staff, lecturers, photocopy budgets, travel funds, graduate funding and other types of expenditures not directly tied to tenured faculty and instruction. In short, in many cases departments are being handed cuts that force them to slash anything that is not committed.

- Early retirement packages are being used to encourage staff and senior faculty to leave. People who take these are generally not being replaced.

- In some places staff, faculty and administration are taking pay cuts or unpaid vacations.

- One place is down to 4 days a week so that they can save on energy costs for the fifth day.

- Some respondents are convinced there is hidden fat in universities that administrators are concealing in order to force change. These respondents think this is a manufactured “new reality”. Whether or not this reality is an appearance or a real reality, the paranoia and antagonism between faculty and administration in some posts is obviously part of what’s happening.

- And yet there are measured notes that suggest some institutions have good lines of communication where the budget realities are shared and departments are given the chance to develop a consensus about solutions.

- Graduate students and new faculty are extremely vulnerable with sessional jobs being cut and no new jobs for those about to finish. In some cases their in-program funding (TAships) is drying up and they don’t know how they will survive.

- There are complaints about investments in non academic functions from sports to new technologies (or the lack of them).

- Relations between universities/colleges and their state or provincial government are crucial. Does the president go public about the need for adequate funding and get into a fight with the state premier? When a state or province has only a couple of universities does that change the situation?

- And some places seem not to be facing significant cuts.

I think many of us are wondering if the cuts will be so deep that administrations start laying off tenured faculty or trying other, more drastic changes. On the one hand tenure seems sacred, on the other hand, why should staff and untenured faculty have to take the brunt of the cutbacks? We have already seen a shift in the ratio of tenured teaching staff to temporary teaching staff. That’s in part what the strike at York was about. Is it fair to protect senior research faculty by expanding the pool of temporary staff who are paid by course and have no security? Do we want a two-class system?

The deeper issue is whether the resources we have per student are being well spent. We keep cutting at a system designed some time ago rather than asking how to design a system in the face of very different funding. We keep cutting in the hope that we can hold out until the good times come again, but they never do (or if they do we don’t hear about them in the humanities.) What if structurally we will never be able to make the case for public funding that health care and road work can and therefore always be a budgetary afterthought? What if the cutting will be continuous for a decade or two until the baby boom and their needs have passed? Would we do things differently? Some possibilities are:

- Someone will have the bright idea that they can cut deeper if they remove the research function. The University of Toronto periodically argues for differential funding – that there should be a small number of universities funded to do research and teaching, and a larger number funded as super-high-schools.

- One advantage of restructuring as community colleges or high schools is that we might then unionize and negotiate as a provincial block. Negotiations might turn to things like class-sizes, contact hours, and the other things that tend to get cut. For that matter unions might represent all staff whether full-time, part-time, faculty, sessionals, or other. Unions that represent us all might be more able to argue for support for the whole over cuts to weaker groups. I’m not advocating this, just recognizing that our college and school colleagues negotiate differently and don’t seem to perpetually get bigger classes.

- Other states might move to a distributed distance model like the University of Phoenix that uses lots of practicioners rather than faculty. The idea would be you get rid of most full-time teaching staff, get rid of the demand for advanced credentials (like the PhD), and open up a teaching market so anyone can bid on teaching tasks if they have some credible experience. (What would experience to teach a philosophy course on “Appearance and Reality” look like?) This would keep teaching costs down, and, if you also get rid of the physical campus, keep the facilities costs down.

- We could see centralization of certain instructional and research functions where a small number of experts at elite institutions do the curricular development, the online streaming lectures, and the research for the rest of us. Poorer places buy services from the few places left that do original work. All you need locally to organize a really big class is a stadium to pipe the lectures into (if they aren’t accessed over the web) and staff to handle the collection of fees, the marking and the credentialing. Any expensive marking, as in reading papers and commenting on them, could be outsourced to the same people who students now pay to write their papers in the first place.

- We might see a return to very small and personal charter schools run by faculty teams who loosely associate with other teams as a “university.” Four faculty could organize a great book curriculum for 100 students (25 students a year for 4 years) as a very small college. Each faculty member could meet each class of 25 for 3 hours a week for a total of 12 hours of teaching a week. They would rent space and access to public library resources. If the 100 students were paying $10,000 each (half of that might be paid by the state) then the team would have a budget of $1,000,000 which could cover salaries, space and resource rentals. Note that such a model would be missing all sorts of things we take for granted at universities, but it would also have some advantages, especially when it came to class size and attention. There would be no administration to speak of, no admission system, no choice when it comes to courses, no support staff, no campus life, no residencies, no assessment of teaching, little research, no labs and so forth. To implement this we would need a dramatic change to how colleges are chartered. Imagine what it would be like if groups of smart graduate students could throw together competitive mini-colleges around cool topics like computer gaming in competition with us.

These are the dramatic (and in some cases horrible) scenarios. I hope that creative administrators with the involvement of their colleagues come up with humane and imaginative design alternatives for discussion. My point is that we do need to be thinking about the very idea of the university. Whatever choices we make, I think it is time to ask how we could run higher-education differently if we were starting from scratch, especially since that is how we will better understand the design of what we have. I suspect nobody wants to ask the question for fear of losing what we think we have before the barbarians, but surely we are committed to inquiry and that involves inquiry into how we run our institutions. If we don’t explore the scenarios others may do it for us with less pleasant results.

Then again this might all blow over.