I was just sent an invitation to IconoTag by an old friend, Jame Turner. It is a multilingual image tagging research project where you choose a language and tag 12 images in that language. I’m not sure what the research is, but it reminds me of the Google’s Image Labeler which seems loosely based on Luis von Ahn’s work – projects like CAPTCHA and reCAPTCHA.

Category: Social Networking

Day of Digital Humanities 2010: You are invited to participate

Well, we are starting up the second Day of Digital Humanities project. You are invited to participate!.

You can see what we did in last year’s project here. The idea was to have digital humanists blog one day of what they did and then combine it all into a dataset that can be studied. We call it “autoethnography of a community.” It was fascinating and stressful to run last year. I’m hoping I can enjoy it more this year.

The project will run on March 18th, 2010. We are hoping that we will get more graduate students and more colleagues from outside North America!

YouTube – Digital Preservation and Nuclear Disaster: An Animation

Seamus pointed us to a great animation on YouTube, Digital Preservation and Nuclear Disaster. They nicely dramatize the challenges and need for digital preservation.

Scott Smallwood and Musical Interactives

Scott Smallwood came to talk to our interactives group about his work on musical instruments. Scott was involved with the Princeton Laptop Orchestra (PLOrk) and demonstrated one of the hemispherical speakers that they designed so that laptop musicians could join and play with others. The idea was that a laptop musician, instead of plugging into a sound system (PA), should be able to make sound from where they are just like the analogue instruments. I wonder what the visualization equivalent is? Will these new pocket projectors we can begin to imagine visualization instrument that are portable. Pattie Maes and Pranav Mistry’s demo of SixthSense at TED is an example of creative thinking about outdoor interface.

Collaboration: Digital Humanities And Computer Science

I have now wrapped up my conference report on the Digital Humanities And Computer Science symposium. At the end I was on a panel on collaboration between the digital humanities and computer science. In many ways the DHCS symposium is an example of collaboration and how to build it. Below are the quotes and theses on collaboration that I spoke to.

Continue reading Collaboration: Digital Humanities And Computer Science

digitalresearchtools / FrontPage

DiRT: Digital Research Tools is an interesting wiki for keeping track of digital research tools. The editors have done a good job – this strikes me as something worth investing in as a place to discover tools for the humanities.

brightkite.com

Twitter is so yesterday … I’m trying out brightkite.com a location-based social network tool. If you download the iPhone app then you can “Check In” so your friends (or everyone) knows where you are (were). Alternatively you can post a note to your (or a nearbye) location or you can post a photo.

Twitter is so yesterday … I’m trying out brightkite.com a location-based social network tool. If you download the iPhone app then you can “Check In” so your friends (or everyone) knows where you are (were). Alternatively you can post a note to your (or a nearbye) location or you can post a photo.

I want to see if this can be used for geo-games or adding a knowledge layer to locations. I can get a “Placestream” by location, but the emphasis of the interface is on friends nearby (all five people in Edmonton that I don’t care about) and what’s happening (the inane “I’m here” posts of the terminally boring.) I want to create a quality layer of location-based knowledge that someone could subscribe to, like a “Local History of Edmonton” that people could turn on to get local history in the wild.

They seem to be collaborating with Layar, which is cool, and they do have an API …

TPM: The Philosophers’ Magazine | The real thing?

Thanks to Peter I came across an article in The Philosophers’ Magazine titled The real thing? (by Julian Baggini, Issue 43, posted May 5, 2009) about social epistemology. Social epistemology according to Alvin Goldman, who was interviewed for the article, examines the social dimension of knowing. Goldman is quoted as saying,

Historically, epistemology focused on how you can get the truth about the world. The question for social epistemology is something like, how does the social affect people’s attempts to get the truth? So what I want to do, and this has been part of my efforts for these 10 years or so, is to try to give a bigger focus to the social side of epistemology, while remaining continuous with the philosophical tradition.

Clickstream Data Yields High-Resolution Maps of Science

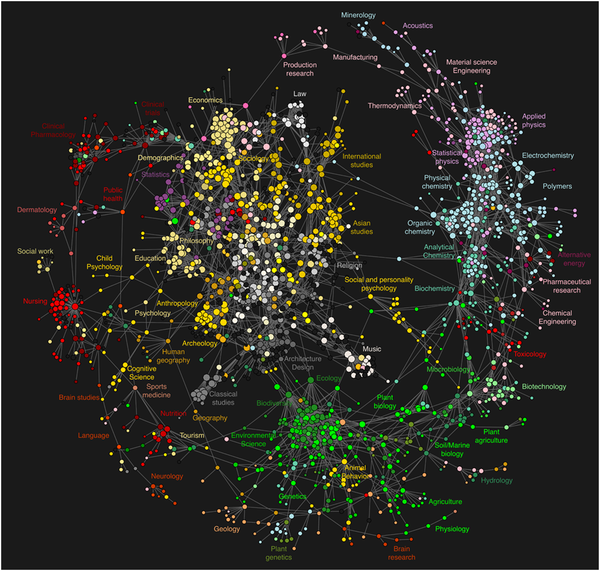

Clickstream Data Yields High-Resolution Maps of Science is an article that presents an interesting view of the interdisciplinary relationships between the humanities and social sciences, on the one hand, and the sciences on the other. The article used “clickstream” data or usage data collected at various scholarly portals that show not citation links but connections in the activities of the users.

Clickstream Data Yields High-Resolution Maps of Science is an article that presents an interesting view of the interdisciplinary relationships between the humanities and social sciences, on the one hand, and the sciences on the other. The article used “clickstream” data or usage data collected at various scholarly portals that show not citation links but connections in the activities of the users.

The resulting model was visualized as a journal network that outlines the relationships between various scientific domains and clarifies the connection of the social sciences and humanities to the natural sciences.

They describe the visual appearance of the visualization (above) thus,

To provide a visual frame of reference, we summarize the overall visual appearance of the map of science in Fig. 5 in terms of a wheel metaphor. The wheel’s hub consists of a large inner cluster of tightly

connected social sciences and humanities journals (white, yellow and gray). Domain classifications for the journals in this cluster include international studies, Asian studies, religion, music, architecture and design, classical studies, archeology, psychology, anthropology, education, philosophy, statistics, sociology, economics, and finance. The wheel’s outer rim results from a myriad of connections in M’ between journals in the natural sciences (red, green, blue). In clockwise order, starting at 1PM, the rim contains physics, chemistry, biology, brain research, health care and clinical trials journals. Finally, the wheel’s spokes are given by connections in M’ that point from journals in the central hub to the outer rim.

This article came out of work funded by Mellon at the MESUR project.

Steve.Museum: Social Tagging Tool

Steve is an open source social tagging tool that lets you publish a collection and collect tags. It is developed by museum folk for research into tagging of cultural objects. It seems to me to be an adaptation of the reCAPTCHA idea or Google’s image tagging game.

Steve is an open source social tagging tool that lets you publish a collection and collect tags. It is developed by museum folk for research into tagging of cultural objects. It seems to me to be an adaptation of the reCAPTCHA idea or Google’s image tagging game.

Our current research project, “T3: Text, Tags, Trust,” a partnership with the University of Maryland’s School, is funded, in part, by a National Leadership Grant for Research from the U.S. Institute of Museum and Library Sciences. Results of a recently-completed IMLS research project, “Researching Social Tagging and Folksonomy in the Art Museum,” are presented in the Research section of this website. Data collected at http://tagger.steve.museum provides a testbed for researching our hypotheses about social tagging.

See the Research section of the site for research results and a dataset for experimentation.

Thanks to Megan for this.