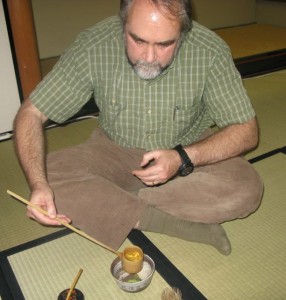

I was recently invited to Ritsumeikan‘s student tea ceremony circle. I watched the students timing each other as they performed the ritualized movements and was then shown how to prepare matcha, which is made from a powdered green tea that is stirred into the hot water with a bamboo whisk. The tea ceremony is a tradition that is focused outwards towards the other that you serve. As such it complements the Zen practice of meditation that is focused inwards on calming the mind.

Following Donal Keene’s comparison of Pachinko to Zen meditation (Zazen) I am tempted to see in the tea ceremony signs of Japanese game culture. In the tea ceremony you can see a passion or obsession similar to that of otaku fans. The picture above shows the tools (Haioshi) a member of the circle was using to sculpt the ash (Hai) in a brazier (Furo) which would be used to heat the water for tea at an upcoming ceremony. The ash in the brazier would be difficult to see, but it still gets the attention of a Zen garden. Likewise the ritualized movement of the ceremony suggests rythm games popular in Japan, though the idea in the tea ceremony is to move slowly and gracefully. The beautiful small tea rooms are small worlds where everything can be set right. And, unlike meditation, the tea ceremony is shared, collaborative play.

Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that the tea ceremony is a form of play in Huizinga’s sense of an activity set apart from the world with its particular magic space, utensils, and movements.