I’m at the Montréal International Games Summit 2010 (MIGS) for today and tomorrow. My conference notes are at Philosophi.ca – MIGS conference report.

Category: Computer Games

Cultivated Play: Farmville | MediaCommons

Thanks to Erik (again) I was pointed to this essay on Cultivated Play: Farmville by A. J. Patrick Liszkiewicz in MediaCommons.

The essay starts by asking why Farmville (a plug-in game for Facebook) is so popular. Why is harvesting virtual pumpkins (lots of clicks) fun for Facebook users? Patrick argues that Farmville is popular because we are polite people who want to be good to each other,

The secret to Farmville’s popularity is neither gameplay nor aesthetics. Farmville is popular because in entangles users in a web of social obligations. When users log into Facebook, they are reminded that their neighbors have sent them gifts, posted bonuses on their walls, and helped with each others’ farms. In turn, they are obligated to return the courtesies. As the French sociologist Marcel Mauss tells us, gifts are never free: they bind the giver and receiver in a loop of reciprocity. It is rude to refuse a gift, and ruder still to not return the kindness. We play Farmville, then, because we are trying to be good to one another. We play Farmville because we are polite, cultivated people.

Liszkiewicz goes on to argue that Farmville resembles work, but it is Zynga (and Facebook) that benefit. This game takes advantage of our natural civility and sense of neighborly obligation to exploit us. He ends up calling ita “sociopathic application” because it exploits our sociability to control us.

As someone who quit Facebook in a huff over how they were exploiting my information I can’t play Farmville and therefore I’m not sure that it has no redeeming qualities. I do, however, agree that we must examine what we are doing and quit those social sites that exploit us.

Glass

Thanks to Erik I have discovered an interesting web annotation feature called Glass. At the moment they are in beta and you have to get an invitation code to get an account, but they aren’t that hard to get.

Glass lets you add glass slides to web pages that you can invite other Glass users to see. These slides can hold conversations about a web site. You could use it to discuss an interface with a graphic designer. There might be educational uses too.

The interface of Glass is clean and it seems to nicely meet a need. Now … can we make a game with it? Can we do with it what PMOG (now called the Nethernet) was doing?

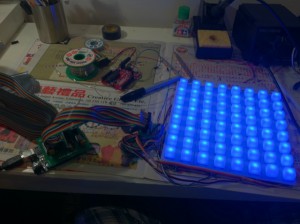

Arduinome@UofA

Garry Wong has finished my first Arduinome. This is a monome built with Arduinos with some customizations. Garry, Calen Henry, Patrick Von Hauff, and Huiwen Ji developed a version of the Arduinome for research into interactivity. They designed a case that can enclose the Arduinome and prototyped some interactive uses for it including a game. Now they are refining the case so it can be ordered from Ponoko by others who don’t have access to a shop. Now we have to come up with ideas for the experiments using the Arduinome.

Seth Priebatsch: The game layer on top of the world

Seth Priebatsch gave an interesting TED talk, The game layer on top of the world. He lists for game dynamics thatcan be used to motivate people.

- Appointment Dynamic – you have to return somewhere to achieve something

- Influence and Status – you play to get badges and other indicators of status

- Progression Dynamic – you have to work up through levels

- Communal Discovery – people work together to solve problems

He argues that the last decade was the decade of social and the next is the decade of games. He wants us to develop the game infrastructure right and use it for good. Facebook dominates the social by running what is effectively the great social graph that joins us. Do we want a single company monetizing our game layer?

A related project is XPArena – “a learning experience points platform” that allows educators to define points for learning achievements. This lets educators turn things into a game.

Thanks to Peter for this.

JSTOR: Journal of Educational Sociology, Vol. 23, No. 4, (Dec., 1949)

In 1944 the Journal of Educational Sociology had an issue on “The Comics as an Educational Media”. The Editorial by Harvey Zorbaugh began by quoting Sterling North of the Chicago Daily News who wrote,

Virtually every child in America is reading color “comic” magazines- a poisonous mushroom growth of the last two years. …

Badly drawn, badly written and badly printed – a strain on young eyes and young nervous systems – the effect of these pulp-paper nightmares is that of a violent stimulant. (p. 193-4)

Zorbaugh and the other authors of the articles collected in this issue are, however, interested in how comics can be leveraged for learning. Zorbaugh ends his editorial with,

It is time the amazing cultural phenomenon of the growth of the comics is subjected to dispassionate scrutiny. Somewhere between vituperation and complacency must be found a road to the under- standing and use of this great new medium of communication and social influence. For the comics are here to stay.

I was struck reading this journal issue how we are going through the same motons with videogames. We have public anxiety about video games, we worry that videogames are violent stimulants, and yet we recognize they are here to stay. Someone gets the bright idea then of trying to create serious games that stimulate the mind, not violence. Academics (like me) follow. Here is the argument from one of the other articles in the issue,

In recent decades, invention and technology have developed motion pictures, the radio, and, latterly, the comic. The first two have already been harnessed to the purposes of education. It is appropriate to examine from the standpoint of educational method this most recently ar- rived entertainment device that has attracted such an extraordinary following. Any form of language that reaches one hundred million1 of our people naturally engages the attention of educationists, whose major activity is communication. (W. W. D. Sones, “The Comics and Instructional Method”, p. 232.)

What then happened to serious comics? I can’t think of any educational comics even though I collected comic books as a kid. Were serious educational comics a failure? If they were, what does that suggest for serious games? It is tempting to say that the lesson of educational comics is that serious games too will vanish as another educational fad. I suspect there are other answers:

- Perhaps serious comics did work. There were, after all, educational comics like GE’s Adventures in Electricity. Perhaps they were effective educational (and promotional) tools even if never as popular with youth as action comics. Now, of course, we have a wealth of serious graphic novels like Maus by Art Spiegelman.

- Perhaps textbooks learned from comic artists and began to use graphic elements where they illustrated the point. Many of the books I read my children like those by David Macaulay (Castle, City, Cathedral, and The Way Things Work) were drawn, though they didn’t use all the comic conventions. The comic may have evolved as it got serious.

- Society eventually finds a way to manage new media. No one thinks comics are poisoning our children any more. Something happened and now comics are not the threat. Hence we don’t need to tame them any more … or perhaps they aren’t the threat because we tamed them?

Gamification – Using game mechanics in business

Slashdot pointed me to an interesting article, Play to win: The game-based economy (CNNMoney.com, JP Mangalindan, Sept. 3, 2010) which is about how companies are using game mechanics to generate business.

Chalk it up to basic human behavior, which game makers have been trying to understand and appeal to for decades. The more effective a game resonates with users, the better its sales. The developer’s goal is to design a structure and system of rules in which players will a) enjoy the process or journey, and b) create a sense of added value. As gamers and developers have found, a fun process coupled with a system for incentives or rewards for a job well done can become downright addictive.

So it’s no surprise to some gamers — including yours truly — that the very same game-play mechanics that hook players are slowly wending their way into other parts of the economy, too.

The article lists some interesting examples like Mint.com which turns personal finance into a game or the Nike+ site and technology.

Erector Set – Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

I just finished Bruce Watson’s book on A. C. Gilbert, the invetor of the Erector Set titled The Man Who Changed How Boys and Toys Were Made. The book doesn’t quite work as either biography or as social history, but it ends by asking why the Erector sets and other construction toys from Gilbert Toys failed in the late 60s. Watson suggests three changes:

- From Edison to Einstein. The first shift was a shift in paradigm from science being about invention (with Edison as the hero) to science being about theory (with Einstein as paradigm.)

- After the A-Bomb. The second shift was the change in how we perceive science after the Atom Bomb. Science was no longer a unquestioned good. Watson suggests that Frankenstein’s Monster (the film with Boris Karloff) also contributed to a changing in attitude towards science.

- The Cool. The final nail was the emergence of teen culture in the 60s – a culture concerned with the cool. Kids who constructed things with Erector sets were seen not as boys, but as nerds.

Toys like Erector, which in its time was very successful, aimed to appeal to boys. They avoided presenting themselves as “educational” as that would be the kiss of death. Instead they were for tinkering and playing engineer. They appealed to parents as a solution to the “boy problem” of energetic boys getting into trouble (something we solve with drugs today.) With time, playing with Erector sets making bridges ceased to appeal to boys as a manly thing to do. It ceased to be cool and boys began to be seen less as a problem than as a market for which entertainment could be designed. Why solve the boy problem when you could feed the cool boys with rock and roll, television and movies. Toys are now sold in conjunction with TV shows (cartoons or other).

Watson ends the book by pointing out that the videogame industry now sells much more than the toy industry – especially the educational toy industry. Videogames are this generation’s boy toys. What will be next? I can’t help wonder if there is a return to construction with all the interest in Arduino’s, fabrication, and robotics.

Why it’s okay to wage joystick jihad – The Globe and Mail

The Globe and Mail today had a story in the Focus section titled, Why it’s okay to wage joystick jihad (Poplak, Richard, Aug. 27, 2010). The story looks at the controversy raised by the forthcoming Medal of Honor game that takes place in Afghanistan and which allows players to play a Taliban fighter. The story quotes MacKay (our minister of defense),

“The men and women of the Canadian Forces, our allies, aid workers and innocent Afghans are being shot at, and sometimes killed, by the Taliban. This is reality,” Mr. MacKay’s statement said. “I find it wrong to have anyone, children in particular, playing the role of the Taliban. I’m sure most Canadians are uncomfortable and angry about this.”

Poplak dismisses (in my mind too quickly) the argument that there is danger in imitating disreputable characters.

Speaking from the position of a frequent playground ersatz robber, I can confirm that role-playing doesn’t necessarily imply empathy and attachment. There is, after all, no appreciable evidence suggesting that children who play Indians are likely to grow up as advocates for Indians’ rights.

The argument from imitation is not that in playing Indians we would sympthize with them; it is that in repeatedly playing and practicing certain activities we would become conditioned by the activities.

What I like about the story is how it engages and quickly surveys the relationship between games and war. Games can be about all sorts of things, but an extraordinary number of them are about war and fighting. Why is it war that we want to play?

Hoppala! Augments

Lucio introduced me to a cool authoring environment from Layar called Hoppala!. Hoppala! Augmentation lets you author a Layar game on a map on the web. You can attach icons, media and text to the mapped points. We are using this as part of an authoring environment for PicoSafari (soon to be called fAR-Play). PicoSafari is a augmented reality game platform that humanities computing and computing science students created. It has been extended so that we can create adventures with questions you have to answer before you can see the next location. Our goal is to make it easy for people to author games and Hoppala! looks like a great tool.