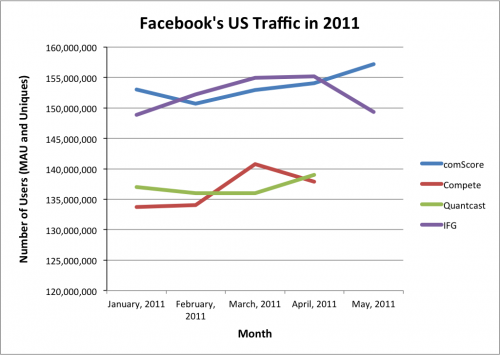

According to Inside Facebook available data shows Facebook user numbers possibly flattening in early-adopter countries like the Canada, UK and the US. This article follows on an article Facebook Sees Big Traffic Drops in US and Canada as It Nears 700 Million Users Worldwide that got a fair amount of press attention. What is going on? In the article about available data they say,

there do appear to be some overriding trends here. Canada, the United Kingdom and a few other early adopting countries have alternately shown gains and losses starting in 2010. Up until then, growth had generally been much steadier.

I doubt this means that Facebook is about disappear. It is still growing world wide. They may just be hitting a saturation point – something you would expect. We might ask if or how Facebook will change once its user base is not expanding. Are they dependent on a perception of growth and will they suffer once Facebook is no longer the hot growing thing? Will users migrate their social networking to the next big thing?

I would add a general reflection which is that there are now more social media sites than I can keep up with. There isn’t enough time to blog, Facebook, Twitter, Flickr and so on. We now have choose that social media that suit our changing lives and where our friends are. My academic friends have migrated to Twitter (while I’m still stuck blogging.) Facebook is what my mother likes. The trick is to not feel one has to keep up with it all.