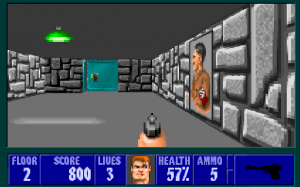

From Slashdot a browser version of Wolfenstein 3D from Bethesda – Celebrating 20 Years of Wolfenstein 3D. You can play the game and choose levels (including secret ones.) There is a nice YouTube video with John Carmack, the director, talking about creating Wolfenstein.

Category: History of Computing and Multimedia

A walk through The Waste Land

Daniel sent the link to this YouTube video, A walk through The Waste Land, that shows an iPad edition of The Waste Land developed by Touch Press. The version has the text, audio readings by various people, a video of a performance, the manuscripts, notes and photos. I was struck by how this extends to the iPad the experiments of the late 1980s and 1990s that exploded with the availability of HyperCard, Macromedia Director and CD-ROM. The most active publisher was Voyager that remediated books and documentaries to create interactive works like Poetry in Motion (Vimeo demo of CD) or the expanded book series, but all sorts of educational materials were also being created that never got published. As a parent I was especially aware of the availability of titles as I was buying them for my kids (who, frankly, ignored them.) Dr. Seuss ABC was one of the more effective remediations. Kids (and parents) could click on anything on the screen and entertaining animations would reinforce the alphabet.

Digital Humanities in Italy: Tito Orlandi

I just got a complementary copy of La macchina nel tempo: Studi dei informatica umanistica in onore di Tito Orlandi (The Time Machine: Studies in humanities computing in honour of Tito Orlandi) which I blogged about before. This got me wondering how much of Prof. Tito Orlandi’s writings are available online and what his legacy is. It turns out that Orlandi has put together a list of his publications with links to online versions where possible. There are even some in English like the excellent Is Humanities Computing a Discipline?

But how might one summarize Orlandi’s contribution? In his prefatory “Controcanto,” one of the editors of The Time Machine, Domenico Fiormonte, writes about first encountering Orlandi in a bunker where Fiormonte then spent a summer. During that summer he learned 3 things:

- Everything that in the humanities is taken for granted (starting with the concept of text) has to be formalized in informatics.

- The passage from analogue to digital is process of profound redefinition for the “cultural object”.

- Thus, every act of encoding (or digital representation) presupposes (or forces us into) a hermeneutical act. (p. VI, my translation)

These three lessons seem about as good a starting place for the digital humanities as any. They also suggest some of what Tito Orlandi was interested in, namely formalization, redefinition, and interpretation. But surveying Orlandi’s writings, using the list of digital humanities publications from his personal site, you can see other themes. He believed that we needed to develop the theoretical foundations of humanities computing and that we should do that from the mathematical model of the computer, not how it works practically. (See Informatica, Formalizzazione e Discipline Umanistiche (in Italian.)) He believed that would help us understand how one can model culture on a computer. He discussed the importance of modelling before Willard McCarty did in Humanities Computing – something that should be recognized out of fairness to the pioneering work of Italian digital humanists since Busa.

Reading Orlandi and about Orlandi I also sense an impatience with those that follow him. This is what he writes in an unpublished talk given in London in 2000. He is talking about discussions by other scholars on the digital humanities.

I feel a sense of inadequateness, even disorder, in the overall change as presented by the same scholars. In fact, when they proceed to propose a definition of humanities computing, they tend to consider the products of computation, be they hardware (the Net) or software (applications like concordance programs or statistical packages), rather than the first principles of computing.

Orlandi wanted to ground the digital humanities in mathematics – a language common to informatics, science and potentially the digital humanities. That the digital humanities wandered off into hypertext, new media and so on seems to have annoyed him. He was also irritated that ideas he had been teaching and writing about for years were being ignored in the English-speaking world. Take a look at The Scholarly Environment of Humanities Computing: A Reaction to Willard McCarty’s talk on The computational transformation of the humanities. This web page discusses an outburst of his at a paper by McCarty with what Orlandi felt were ideas he had been discussing for a decade at least. It is instructive how he sets aside his pride to get at the issues that matter. He might be irritated, but he also wants to use this to reflect on more important issues.

Perilli and Fiormonte have done a great job bringing together a festschrift in honour of Orlandi. The Time Machine isn’t really about Orlandi’s thought so much as about his legacy in Italy. What we need now is for his foundational works to be translated and a retrospective interpretation of his contributions.

The Art of Video Games at the Smithsonian

Arts Technica has a photo essay on the Smithsonian American Art Museum show The Art of Video Games. The Smithsonian site for the exhibit is here.

From the photographs it looks like they didn’t just do the usual think of showing screen shots and concept art as art, but they have sequences of screens titled “Avances in Mechanics” that show, for example, how jumping has changed in games over time. The exhibit also seems to have a historical bent:

The Art of Video Games is one of the first exhibitions to explore the forty-year evolution of video games as an artistic medium, with a focus on striking visual effects and the creative use of new technologies. It features some of the most influential artists and designers during five eras of game technology, from early pioneers to contemporary designers. The exhibition focuses on the interplay of graphics, technology and storytelling through some of the best games for twenty gaming systems ranging from the Atari VCS to the PlayStation 3. (from the exhibit site)

After the Day of DH 2012

Well the Day of Digital Humanities 2012 seems to have gone well. You can see all the activity here. Participants are still catching up with their posts and commenting on each other’s posts. This year we had over 300 participants (332 at last count) though many may not have filled in their blog or registered more than once.

A common concern is that the Day of DH could degenerate into navel gazing. Dan Cohen described the uncharitable possibility succinctly in his post What Is Day of DH? Charitable and Uncharitable Views:

24 hours of navel-gazing and obsessive self-recording by members of a relatively young, slightly insecure field that already spends too much time defining itself or arguing over the definition of digital humanities, even though they basically agree.

I’m obviously the last person anyone should ask about the Day of DH project as I’m part of the team that thought it up and runs it. I do, however, think Dan has put his finger on something important, and that is the youth of the field and the dangers/gifts of youth. Despite decades of humanities computing activities (I’ve been going to conferences since 1989), the field is just becoming a discipline and in this transformation we are likely to exhibit some of the enthusiasms of youth.

But first, Why do I say that we are young? While I believe we have been an interdisciplinary field since the journals in the 1960s and the conferences of the 1970s, I don’t think we became a discipline until we developed the graduate courses, projects, apprenticeships, and programs capable of reproducing practices. When did that happen? I could point to the Kings College London MA in Digital Humanities running in the 1990s, the courses, programs and department I helped develop at McMaster in the 1990s, or the University of Alberta’s MA in Humanities Computing developed by Susan Hockey before she left for UCL. Perhaps it was when the question of disciplinarity itself was debated over a year at the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities at the University of Virginia in a symposium entitled, Is Humanities Computing an Academic Discipline? Sometimes asking the question is its own answer.

Or it could be the extraordinary experiment taking place right now in Ireland with their Structured PhD in a Digital Arts and Humanities. While the rest of us are still thinking and consulting about PhD programs, a network of Irish universities accepted 46 PhD students last year. While I knew about the proposal, only being here for a month and meeting the DAH students have I come to realize what an extraordinary venture this is. Very little seemed to be happening in Ireland before the Digital Humanities Observatory started in 2008, though that may just my impression. Now, four years later, you have a coordinated network of seven universities collaboratively running a PhD program with support from the government and the involvement of the DHO. Of course there are all sorts of wrinkles they have to work out (like the fact that the government funded the students, but not new faculty lines), but there is no denying that this PhD has changed the landscape. 46 students (along with the M. Phil students also admitted at some of the universities) are negotiating what the field is and with relatively little hard supervision. There is no canon, few experienced faculty, and no tradition as to what a PhD in Digital Arts and Humanities should be; so these students and their supervisors are working it out. That is youth! We have much to learn from what they do.

And such negotiation by new digital humanists is what I noticed reading the Day of DH 2012 feed. A cohort of new scholars comfortable with new media are using the Day of DH to have an unconference about what it is to do the digital humanities. I don’t think it is navel gazing; nor do I think it is a sign of insecurity. If anything there is a enthusiasm of being part of something. It is us older folk who are insecure about these new types of events that, frankly, we can’t control. We are also tired of defining the field, but that doesn’t mean that we should deny the pleasure of redefining it to others. The Day of Digital Humanities, like the discipline, is what youthful new scholars will make of it.

So then, what are some of the dangers and gifts of this disciplinary youth?

Near Futures for the Digital Humanities

On Friday I went down to Cork to give a talk on Near Futures for the Digital Humanities at University Collge Cork (Ireland). UCC is one of the universities that are offering the Structured PhD in Digital Arts and Humanities (DAH) so I had a chance after the talk to learn about the program and how it is developing.

The topic of my talk is one we all love to speculate about but should also be careful about as predictions about the future are often so wrong (or so about us now.) I titled my talk “Near Futures” because I wanted to stick to what is near AND talk about how we get near to the future through imagining possibilities (and building possibilities.) The digital humanities has, I think, a different relationship with future humanities than other disciplines that are more focused on the past. That is not to say that other disciplines don’t imagine the future, it is just to say that the digital humanities has to navigate the tide of futurism in computing in general.

IBM Sage Computer, 1960 from the Retronaut

Thanks to the Guardian I discovered the Retronaut, a site dedicated to past visions including past visions of the future. They have a number of interesting things like a video of the IBM Sage Computer, 1960 or Video Games Then and Now. There is a prescient Telecommunications Services for the 1990s created in 1969 for the Post Office Research Station of the UK in 1969.

The machine in time: In honour of Tito Orlandi

Domenico pointed me to an entry on InfoLet (a blog he and others keep in Italian on informatics and literature.) The entry announces a book La macchina nel tempo: Studi di informatica umanistica in onore did Tito Orlandi that brings together many of the top digital humanists in Italy to celebrate Tito Orlandi’s contribution to the field. You can order online at http://www.lelettere.it. Continue reading The machine in time: In honour of Tito Orlandi

The Sketchbook of Susan Kare, the Artist Who Gave Computing a Human Face

Steve Silberman has writing a great story about The Sketchbook of Susan Kare, the Artist Who Gave Computing a Human Face. Susan Kare was the artist who was hired to design fonts and icons for the Mac. She designed the now “iconic” icons in a graph paper sketchbook. The story was occaisioned by the publication of a book titled, Susan Kare Icons which shows some of the icons she has created over the years. (She also has prints of some of the more famous icons like the Mac with a happy face.

The Strange Birth and Long Life of Unix

Also from Slashdot a feature about The Strange Birth and Long Life of Unix. Warren Toomey, a historian of Unix, wrote this feature for the IEEE Spectrum in honour of Unix turning 40.

The creation of Unix (which originally stood for “Un-multiplexed Information and Computing Service”) is tied to text editing as Thomson and Ritchie pitched a proposal to Bell Labs management not as an operating system project but as a project to “create tools for editing and formatting text, what you might call a word-processing system today.” One of the first programs was roff, a text formatting tool. The first tests where for entering and formatting patent applications.

At the end of the feature Toomey talks about the historical work he and others are involved in curating old Unix versions through the Unix Heritage Society.

Our goal is not only to save the history of Unix but also to collect and curate these old systems and, where possible, bring them back to life. With help from many talented members of this society, I was able to restore much of the old Unix software to working order, including Ritchie’s first C compiler from 1972 and the first Unix system to be written in C, dating from 1973.