On November 26th I visited the Toei Kyoto Studio Park for the Uzumasa Sengoku Festival. I’ve posted my photographs here. The Toei Park is cinema theme park with sets that are still used along with all sorts of activities for visitors like a Ninja show. It is a bit of tourist trap, but that is part of its charm for those who want to be photographed in “authentic” settings as you will see. The Uzumasa Sengoku Festival is a two-day festival dedicated to Japanese Warring Period transmedia (manga, anime and games) which made is a perfect venue to study the interplay between media and/for fans. For the festival there was a pavillion dedicated to gaming where local game companies had booths, there were special events and some of the houses in the “historic” Kyoto setting were used by companies to promote new products about popular warring period anime and related media. Above all the cosplay (costume play) fans came out in droves to pose for pictures in the recreated streets of old Kyoto.

Continue reading Uzumasa Sengoku Festival

Category: Japan

Conference Report on DH-JAC2011

I am at the 2nd International Symposium on Digital Humanities for Japanese Arts and Cultures, DH-JAC 2011. I am writing a live conference report here on philosophi.ca. Yesterday I presented a response to Mitsuyuki Inaba’s survey of the work of the Web Technologies group (PDF) of the Global COE Digital Humanities Center for Japanese Arts and Cultures.

Motion Capture and Noh

On November 10th I was invited by Dr. Kozaburo Hachimura to watch as his graduate students capture the motion of a master Noh performer. The motion capture was run in a special lab that was specifically built for this. They have a floor that was built to Noh theatre standards and we had to take our slippers off to protect the wood. There is a rig on the ceiling with the motion capture cameras and a sound booth in the back. When not in use for motion capture the room is used for seminars and meetings.

Downturn in the Japanese Game Industry

Much of the discussion around the games industry here in Japan is taken up by the difficulties big companies like Nintendo are going through. Given that the big companies dominate the scene and that game studies here pay a lot of attention to industry, this means that most discussions with games researchers eventually circle around to the downturn in the industry and what Japan can do about it. But, what exactly is the problem with the Japanese games industry? Here are some of signs that worry games researchers here:

- Smart-phones are replacing dedicated mobile game systems like the Nintendo DS and the Sony PSP in terms of game sales. A story in the Globe and Mail points to a blog entry by Flurry blogger Peter Farago asking Is it Game Over for Nintendo DS and Sony PSP? (Nov. 9, 2011) The is based on US data that shows that between 2009 and 2011 Nintendo and Sony went from owning 81 % of the portable game software market to only 42% of the market.

- Nintendo posted its first ever loss. Nintendo is losing money as reported in a story in the Globe by Yoshiyuki Osada and Isabel Reynolds, Nintendo to post first every annual net loss. On Thursday, Oct. 27th, 2011 Nintendo said it expected its first annual loss ever and attributed it to weak demand for the 3DS (due partly to lack of games that exploit the 3D) and a strong yen (which affects Nintendo because a large percentage of their sale are exports.)

- Japanese game developers seemed to be slow to take advantage of the emerging markets of social games and casual games. Japan’s largest social network Mixi, for example, doesn’t seem to be gaining members and their operating profit is dropping. Most developers seem to be designing games only for the Japanese market leaving the global market to others. Only recently is DeNA moving their Mobage gaming network to Android and iOS and the Android version isn’t getting good reviews.

There is another side to the story. As Ashton Raze puts it in a the Telegraph Super Mario 3D Land review (Nov. 18, 2011),

While current talk of Nintendo is often mired in share prices and falling stocks, it’s easy to forget that they also make games like this; joy-filled, effortless romps, pure blue-sky gaming that can easily be hailed as the reason to own a given system.

Nintendo has also been here before. Osamu Inoue in a somewhat enthusiastic book Nintendo Magic documents how Satoru Iwata (the current president of Nintendo) led the company to record profitability after the poor performances of the Virtual Boy, N64, and GameCube. Eventually they got it right with the DS and Wii. Nintendo has the cash reserves and creativity reserves to weather poor years and systems that aren’t hits. The question is whether a strategy of focused on selling tightly coupled systems and software will work now that smartphones are powerful enough to be mobile systems, and gamers are moving to casual social games and large-scale virtual game worlds all playable on PCs? Who needs dedicated mobile systems or consoles?

Some of the questions that come up when we discuss the perceived downturn are:

- Is there really a problem? What is the scale of the downturn? Is it the Japanese game industry in general or particular companies like Nintendo or just a strong yen?

- What are the causes of the downturn? Is it due to a failure to anticipate new gaming models from MMORGs to social games? Is it due to conservative thinking by management in the industry? Is it due to a dominance of console/system thinking? Is it due to a strong yen or poor global business strategies? Or is it due to a shrinking population of new players and developers?

- What can government do to help? The Japanese government has traditionally not supported their manga/anime/game industries the way they were involved with other industries. There are signs the government is now getting involved – is that a good thing? Does coordinated planning work?

- What are Japan’s strengths? What can they build on to resurrect the games industry?

- What role can the academy play in this? What should be taught? What sort of research would benefit the industry?

- What should be next for the games industry in Japan? Should they keep on doing what they do best or should they refocus? How can industry, academy and government together reinvigorate the export industry?

Cafe la siesta – 8-bit Edition Game Bar

There are small themed bars in all the Japanese cities. They can by 7 floors up by elevator with a little billboard on the street or down a corridor off a back alley with nothing to advertise the bar on the street. Café la siesta is just such a bar in Kyoto dedicated to the generation of 8-bit games like the NES.

Den-Den Town – Annotated Photographs

I have posted a large set of photographs about Den-Den Town, also known as Nipponbashi. This is a neighborhood of Osaka that I visited with Jaakkoo Suominen especially to see the retro-gaming stores where you can buy old game systems and games.

I’m slowly going through the images and annotating them and I’ll probably go back with more specific questions. I took a couple of the eroge (erotic games) because there were so many and it is so clearly a big part of the game industry here in Japan (see this article on Dating simulator games inspire legion of followers – and detractors.) I have blurred out any details of private parts for the sake of decency.

I also took photographs of other things as we worked our way from game store to game store including the picture above of the street person on the main street with their belonging tidly packed up under a tarpaulin. I was struck by the contrast between the busy stores full of old toys and the man peacefully sleeping there in Den-Den town.

RCGS Part 3: Game studies beyond Japan and other issues

How do Japanese researchers see the globalization of games? As I mentioned in my last post, games researchers in Japan are negotiating their field and how it will intersect with game studies elsewhere. While there seemed to be a consensus that they needed to be sufficiently fluent in English to both read and publish in English (the way engineering or medical researchers here do), they don’t see globalization the way we do. First of all games research here is much more interested in supporting industry than game studies in the West. What they call game studies here spans both what we call game studies and the work done in computer science, engineering, and business that work closely with industry. Game studies here is imagined to be supportive of industry in the sense that it should produce well trained students and their research should benefit industry. By contrast, game studies in the West like many humanities and social science fields, is imagined as needing a critical relation with industry. I will be looking more at the relationship with industry in other posts as it came up in many interviews, for the moment let me draw attention to the importance of Asia to Japanese game studies. Japanese youth culture exports well to Asia giving Japan “soft power” in the region, but Japan is also beginning to outsource content creation to countries like China where animators are cheaper. As one can imagine, Asia is Japan’s neighborhood historically, culturally and now economically in a way that it is not for Canada. One of the experts here in Japan on the Asian game market is Professor Nakamura.

Continue reading RCGS Part 3: Game studies beyond Japan and other issues

RCGS Part 2: Games Research in Japan

What is the state of game studies in Japan? The inaugural conference of the Ritsumeikan Center for Game Studies (RCGS) that I blogged about before, had a session titled “Game Studies in Japan: Past and Future” that was dedicated to introducing game studies in Japan to the Ritsumeikan audience through speakers invited from other universities. While one session with three speakers hardly covers the variety of game studies in Japan, it (and the discussion that followed) were my introduction to how the Japanese talk about the field among themselves.

Ritsumeikan Center for Game Studies

Note: This is the first in a series of blog posts about Japanese Game Culture and Game Studies. Thanks go to the support of GRAND, The Ritsumeikan Art Research Center and the Japan Foundation.

Part 1: Setting the Scene

What better way to introduce game studies in Japan than to describe the Game Studies in Progress symposium held to celebrate the inauguration of the Ritsumeikan Center for Game Studies (RCGS). As I was in town thanks to support from the Japan Foundation, I was invited to be one of the guest speakers at a half-day conference on October 14th that kicked off the new center. The creation of the RCGS, which might also be translated “Ritsumeikan Games Research Center,” is one of the outcomes of a major research investment on the part of the Japanese government in a Digital Humanities Center for Japanese Arts and Culture.

The conference was held at the Art Research Centre building of Ritsumeikan University in a special room outfitted with a motion capture system and a sprung-wood floor suitable for Noh performances. One of the research groups of the Digital Humanities Center is the Digital Archives Technologies Group that is experimenting with ways of digitizing cultural heritage traditions like the Japanese Tea Ceremony or Kabuki. These traditions challenge classical Western ideas about what constitutes heritage. There are no archaeological digs, cathedrals or paintings to digitize when trying to preserve Bunraku puppet theatre; instead it is a tradition of oral teaching and performance that they are trying to support through digitization. So there we were in this special room dedicated to a 1000-year old art inaugurating the first explicitly named game studies centre. We were reminded of this as the floor was covered, we all had to leave our shoes at the front (something unusual for university buildings in Japan though common in houses and shrines) and we were reminded not to bring in any food or drinks. It was as if we were in a Zen temple to talk about that most postmodern of subjects, the videogame.

To accommodate the two foreign speakers – myself and Professor Jaakko Suominen of the University of Turku Finland, they had kindly found the extra funding for the translation services described above. For two of us they had a team of at least three translators and staff! Not for the first time I was awed by the hospitality of my hosts. Not for the first time I don’t feel worthy. Not for the first time I feel like a bit of fraud on a paid vacation to learn about Japanese game culture when there must be better cultural interpreters out there. I reassure myself by immersing myself every day so I can reflect some of this back to readers and that’s what these blog posts are about.

A word of warning, Suominen and I listened through earphones to a simultaneous translation of the talks in Japanese which means that I may not have accurately understood everything said. Again, language is one of the problems cross-cultural researchers in game studies have to overcome and it came up at the conference over and over, but more on that later. For this first entry, however, let me introduce the opening speaker, Professor Uemura pictured here.

Opening by Professor Uemura, Director of the RCGS

Professor Uemura is best known as the lead engineer who led the development of the Famicom which was called the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) in North America. Uemura, who is still a consultant with Nintendo, kicked off the conference by talking about the variety of research taking place already at Ritsumeikan and his dreams for the centre. He listed some of the objectives for the center:

- First, it will bring together people across Ritsumeikan already doing games research. While the RCGS was officially only formed in April of 2011, there is already considerable depth at Ritsumeikan. The Video Game Archive Project has been going since 1998 and there is overlap with other digital arts and culture projects experimenting with virtual worlds for learning and historical GIS. There is also a College of Image Arts and Sciences with undergraduate and graduate programmes that include animation and game design.

- Second, the RCGS will communicate with other researchers in Japan and overseas. (That’s Dr. Suominen and I were invited to talk and why there was a session with researchers from other universities in Japan.)

- Thirdly, the RCGS will collaborate with industry. This will be the hardest objective as Nintendo, the major local game company, is notoriously private and there is little history of industry/academy collaboration. This issue came up politely in the conference.

Professor Uemura then surveyed the types of research already taking place at Ritsumeikan:

- As mentioned above there is research on archiving games, the gaming experience and the history of games. Researchers are, for example, starting work on interviewing early game designers, scanning manuals, and looking at the history of arcades.

- There is significant work around serious games and the use of virtual worlds in education.

- An important area of research for industry is around intellectual property rights and international law.

- Researchers are looking at entrepreneurship and games.

- There is theoretical work on how to define games and methodological work on how to assess them.

- Researchers are looking at the Asian game market. They are looking at the reception of Japanese games in countries like China. How are games infectious?

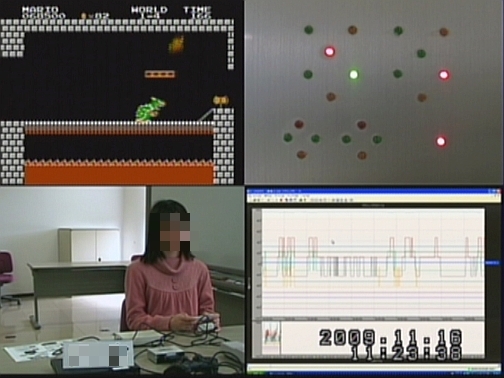

Professor Uemura himself is studying game play on the Famicom looking for patterns in play. He has a set up which allows him to record input and output from a game while also capturing what is on the screen and video of the player. With this he can then look at rhythms of play and compare play.

Slide showing the game play capturing system developed by Uemura (from a talk in Japanese)

Slide showing the game play capturing system developed by Uemura (from a talk in Japanese)

Uemura concluded by emphasizing that he wants the RCGS to be a place for play – a place for fun and entertainment with games not just the serious study of games. Games should be fun he said, so games research should be fun. The idea is not research for the sake of research, but a research centre that is like an arcade. In his experience the difference between industry and academy is that in industry people have fun at what they are doing and he hoped that would be true of the RCGS too.

It is worth noting that there was an excitement to the symposium and generally an openness not always found elsewhere. The feel of the symposium was that participants were at the birth of something that they could participate in as game studies is just gaining academic credibility in Japan. As others pointed out game studies in Japan is just in its infancy which for the participants means that there is none of the unwelcome turf wars we see in game studies in the West. In Japan they seem to have missed the ludology vs. narrativity battles.

Next: Part 2: Games Research in Japan

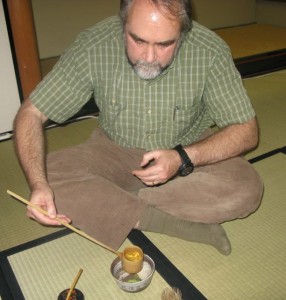

Japanese tea ceremony

I was recently invited to Ritsumeikan‘s student tea ceremony circle. I watched the students timing each other as they performed the ritualized movements and was then shown how to prepare matcha, which is made from a powdered green tea that is stirred into the hot water with a bamboo whisk. The tea ceremony is a tradition that is focused outwards towards the other that you serve. As such it complements the Zen practice of meditation that is focused inwards on calming the mind.

Following Donal Keene’s comparison of Pachinko to Zen meditation (Zazen) I am tempted to see in the tea ceremony signs of Japanese game culture. In the tea ceremony you can see a passion or obsession similar to that of otaku fans. The picture above shows the tools (Haioshi) a member of the circle was using to sculpt the ash (Hai) in a brazier (Furo) which would be used to heat the water for tea at an upcoming ceremony. The ash in the brazier would be difficult to see, but it still gets the attention of a Zen garden. Likewise the ritualized movement of the ceremony suggests rythm games popular in Japan, though the idea in the tea ceremony is to move slowly and gracefully. The beautiful small tea rooms are small worlds where everything can be set right. And, unlike meditation, the tea ceremony is shared, collaborative play.

Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that the tea ceremony is a form of play in Huizinga’s sense of an activity set apart from the world with its particular magic space, utensils, and movements.