Information is Beautiful has a great interactive on World’s Biggest Data Breaches & Hacks. The interactive shows how data breaches are getting worse, but it also lets you look at different types of breaches.

Category: Visualization

They know (on surveillance)

They know is a must see design project by Christian Gross from the Interface Design Programme at University of Applied Sciences in Potsdam (FHP), Germany. The idea behind the project, described in the They Know showcase for FHP, is,

I could see in my daily work how difficult it was to inform people about their privacy issues. Nobody seemed to care. My hypothesis was that the whole subject was too complex. There were no examples, no images that could help the audience to understand the process behind the mass surveillance.

The answer is to mock up a design fiction of an NSA surveillance dashboard based on what we know and then a video describing a fictional use of it to track an architecture student from Berlin. It seems to me the video and mock designs nicely bring together a number of things we can infer about the tools they have.

Past Visions

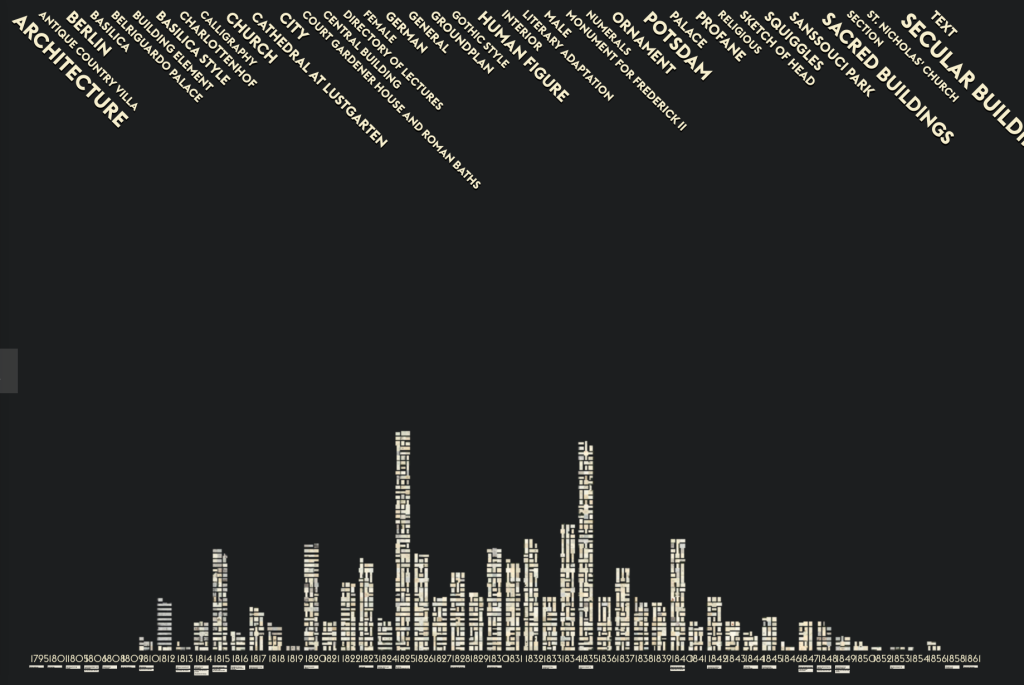

Past Visions: penned by Frederick William IV is a lovely visualization of hist historical sketches and doodles. The visualization has a rich prospect view where you see miniatures of all the sketches arranged over time. You can pan in and out or use the keywords to see subsets. There is information available about each sketch (in German.)

This visualization was developed by the research project VIKUS – Visualising Cultural Collections at the University of Applied Sciences Potsdam. Thanks to Johanna for introducing it to us.

Replication as a way of knowing in the digital humanities

At the end of April I gave a talk at the University of Würzburg on Replication as a way of knowing in the digital humanities. This was sponsored by the Dr. Fotis Jannidis who holds the position of Chair of computer philology and modern German literature there. He and others have built a digital humanities program and interesting research agenda around text mining and German literature. The talk tried out some new ideas Stéfan Sinclair and I are working on. The abstract read:

Much new knowledge in the digital humanities comes from the practices of encoding and programming not through discourse. These practices can be considered forms of modelling in the active sense of making by modelling or, as I like to call them, practices of thinking-through. Alas, these practices and the associated ways of knowing are not captured or communicated very well through the usual academic forms of publication which come out of discursive knowledge traditions. In this talk I will argue for “replication” as a way of thinking-through the making of code. I will give examples and conclude by arguing that such thinking-through replication is critical to the digital literacy needed in the age of big data and algorithms.

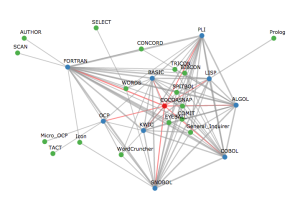

The Rise and Fall Tool-Related Topics in CHum

I just found out that a paper we gave in 2014 was just published. See The Rise and Fall Tool-Related Topics in CHum. Here is the abstract:

What can we learn from the discourse around text tools? More than might be expected. The development of text analysis tools has been a feature of computing in the humanities since IBM supported Father Busa’s production of the Index Thomisticus (Tasman 1957). Despite the importance of tools in the digital humanities (DH), few have looked at the discourse around tool development to understand how the research agenda changed over the years. Recognizing the need for such an investigation a corpus of articles from the entire run of Computers and the Humanities (CHum) was analyzed using both distant and close reading techniques. By analyzing this corpus using traditional category assignments alongside topic modelling and statistical analysis we are able to gain insight into how the digital humanities shaped itself and grew as a discipline in what can be considered its “middle years,” from when the field professionalized (through the development of journals like CHum) to when it changed its name to “digital humanities.” The initial results (Simpson et al. 2013a; Simpson et al. 2013b), are at once informative and surprising, showing evidence of the maturation of the discipline and hinting at moments of change in editorial policy and the rise of the Internet as a new forum for delivering tools and information about them.

three dimensional dynamic data exploration for dh research

I’m blogging now at Three dimensional dynamic data exploration for DH research. This the project that brought me to Hamburg for these three months so most of my blog entries will be on that site. The project is developing ideas for a next generation visualizations for the humanities.

IBM to close Many Eyes

I just discovered that IBM to close Many Eyes. This is a pity. It was great environment that let people upload data and visualize it in different ways. I blogged about it ages ago (in computer ages anyway.) In particular I liked their Word Tree which seems one of the best ways to explore language use.

It seems that some of the programmers moved on and that IBM is now focusing on Watson Analytics.

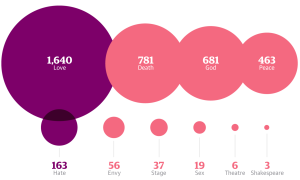

What’s in a number? William Shakespeare’s legacy analysed

The Guardian published an article on What’s in a number? William Shakespeare’s legacy analysed (April 22, 2016). This article is part of a Shakespeare 400 series in honour of the 400th anniversary of the bard’s death. The article is introduced thus:

Shakespeare’s ability to distil human nature into an elegant turn of phrase is rightly exalted – much remains vivid four centuries after his death. Less scrutiny has been given to statistics about the playwright and his works, which tell a story in their own right. Here we analyse the numbers behind the Bard.

The authors offer a series of visualizations of statistics about Shakespeare that are rather more of a tease than anything really interesting. They also ignore the long history of using quantitative methods to study Shakespeare going back to Mendenhall’s study of authorship using word lengths.

Mendenhall, T. C. (1901). “A Mechanical Solution of a Literary Problem.” The Popular Science Monthly. LX(7): 97-105.

Literature Measured

I finally got around to reading the latest Pamphlets of the Stanford Literary Lab. This pamphlet, 12. Literature Measured (PDF) written by Franco Moretti, is a reflection on the Lab’s research practices and why they chose to publish pamphlets. It is apparently the introduction to a French edition of the pamphlets. The pamphlet makes some important points about their work and the digital humanities in general.

Images come first, in our pamphlets, because – by visualizing empirical findings – they constitute the specific object of study of computational criticism; they are our “text”; the counterpart to what a well-defined excerpt is to close reading. (p. 3)

I take this to mean that the image shows the empirical findings or the model drawn from the data. That model is studied through the visualization. The visualization is not an illustration or supplement.

By frustrating our expectations, failed experiments “estrange” our natural habits of thought, offering us a chance to transform them. (p. 4)

The pamphlet has a good section on failure and how that is not just a rhetorical ploy, but important to research. I would add that only certain types of failure are so. There are dumb failures too. He then moves on to the question of successes in the digital humanities and ends with an interesting reflection on how the digital humanities and Marxist criticism don’t seem to have much to do with each other.

But he (Bordieu) also stands for something less obvious, and rather perplexing: the near-absence from digital humanities, and from our own work as well, of that other sociological approach that is Marxist criticism (Raymond Williams, in “A Quantitative Literary History”, being the lone exception). This disjunction – perfectly mutual, as the indiference of Marxist criticism is only shaken by its occasional salvo against digital humanities as an accessory to the corporate attack on the university – is puzzling, considering the vast social horizon which digital archives could open to historical materialism, and the critical depth which the latter could inject into the “programming imagination”. It’s a strange state of a airs; and it’s not clear what, if anything, may eventually change it. For now, let’s just acknowledge that this is how things stand; and that – for the present writer – something needs to be done. It would be nice if, one day, big data could lead us back to big questions. (p. 7)

Hermeneutica

MIT Press has posted the cover for the book they are publishing that I wrote with Stéfan Sinclair, Hermeneutica! It is finally happening. Now we have to get the web site and Voyant 2.0 wrapped.

What’s particularly humbling are the endorsements from Johanna Drucker, Chad Gaffield, Dan Cohen and Willard McCarty.