What if you only remembered what you had read? In Umberto Eco’s latest novel, The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loanna, the narrator Bodoni wakes from a stroke with no memories other than the cultural ones – what he, an antiquarian book collector, has read. The first two parts of this novel dramatize the personal (and its loss) in memory. What if memory were only a hypertext of associations like Bodoni’s memories? What makes a memory meaningful? What gives it the “mysterious flame” of immortality?

What if you only remembered what you had read? In Umberto Eco’s latest novel, The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loanna, the narrator Bodoni wakes from a stroke with no memories other than the cultural ones – what he, an antiquarian book collector, has read. The first two parts of this novel dramatize the personal (and its loss) in memory. What if memory were only a hypertext of associations like Bodoni’s memories? What makes a memory meaningful? What gives it the “mysterious flame” of immortality?

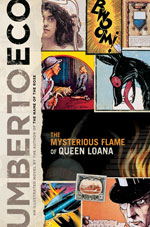

The novel draws its name from a comic book from Eco’s youth that was based on a novel She by H. Rider Haggard (1886). The narrator tries to recover his memory returning to his grandfather’s country estate in the town of Solara and reading through the adventures and comics of his youth. Eco uses this to trace Italian fascism through its impact on popular youth culture, reproducing through the novel illustrated images, especially comics, from his youth.

In the third and final part Bodoni has another stroke and in his coma trys to see the face of his first love, Sibilla (Sibyl). Eco is playing with myths, both those of comic books and the Greek ones of return. The Cumaean Sibyl leads Aeneas into the caverns of Hades to see his father just as Bodoni is led into the caverns of memory where he finds his childhood with his father. Bodoni, named after the type designer Giambattista Bodoni, seeks but cannot recover, the memory of his Sibilla – he has no way back. He is lost in the caverns of what can be read and can’t find his way back to the sun – Solara. The novel ends with the smoke of memory eclipsing that sun.

I feel a cold gust, I look up.

Why is the sun turning black?

Eco’s novel, like Baudolino before, also feels like it doesn’t know when to return. Both begin well and then get lost in antiquarian detail. Eco doesn’t know when to stop, when to return home and leave the loving details to others. Is this the curse of scholastic writers?

Continue reading The Fog of Memory: Eco and “The Mysterious Flame of Queen Loanna”

Joanne, my hard cover muse, lends me books that win prizes (or almost win.)

Joanne, my hard cover muse, lends me books that win prizes (or almost win.)